|

|

Bears I Have Met: The Stories of Monarch and Pinto

Chapters 2, 17 and 18 from

"Bears I Have Met — and Others"

By Allen Kelly

| Philadelphia: Drexel Biddle, Publisher | 1903

|

• CHAPTER II: THE STORY OF MONARCH. Webmaster's Notes. About the only thing bigger than grizzly bears in the wild are the wild tales that have been told about them. One locally famous story involves John Lang (of Lang Station fame), who settled in Soledad Canyon in 1870 and is said to have shot a grizzly in 1873 that weighed a fantastic 2,350 pounds. Supposedly its hide was sent to a museum in Liverpool, England. (Note: The story stretched over the years. Lang himself said it weighed 1,600 pounds and he shot it in 1875.)

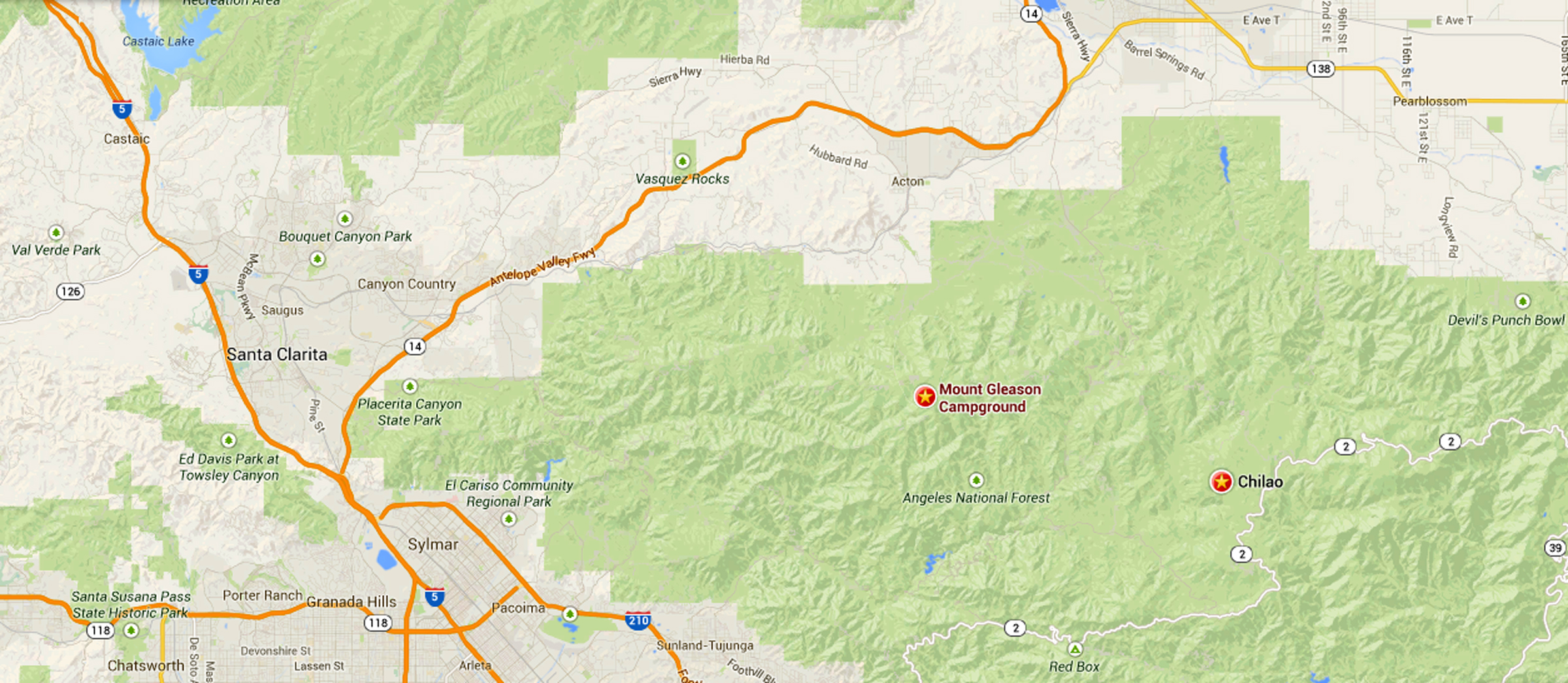

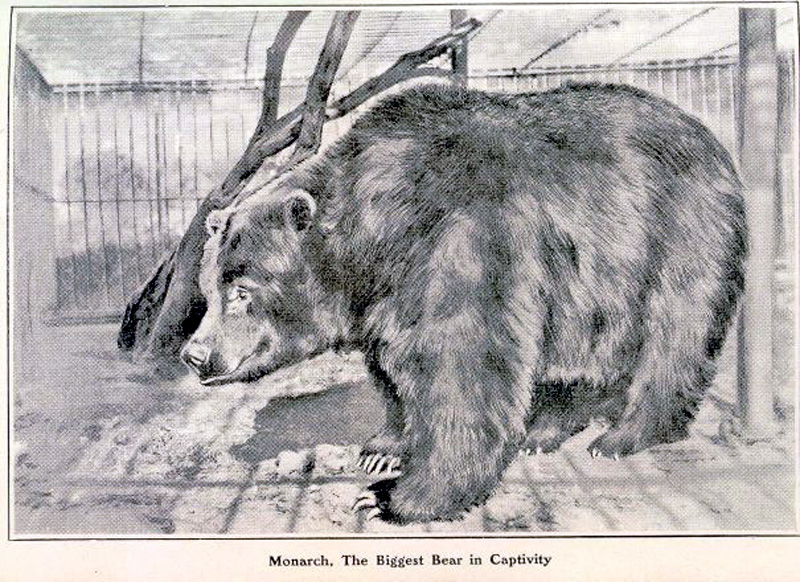

Kelly was long on enthusiasm and short on know-how when it came to trapping large animals. He spent considerable time exploring the "mountains of Ventura county" (reportedly the Ojai area) and soon realized nobody else knew how to catch a grizzly either, although many insisted they did. Kelly then headed northeast to the Tejon Ranch, roughly between Lebec and the Tehachapis, where an old grizzly named Pinto had been terrorizing cattle. Kelly struck out there, too. (When Old Pinto was finally brought down and some of his remains were weighed at a butcher shop, he was estimated at 1,100 pounds, which was considered large. The only bears that weighed significantly more, Kelly writes, "have all been weighed by the fancy of the men who killed them, and the farther away they have been from the scales, the more they have weighed.") By this time the locals had caught on to what Kelly was doing in the area. It was a large expanse but a sparsely populated one, and word spread quickly of this big-city urbanite who was trying to trap a grizzly. Folks had visions of $20 gold pieces piled high, and soon everyone was offering to catch one for him. It finally happened in October 1889 at Mount Gleason in the San Gabriels (now the Angeles National Forest) east of the Santa Clarita Valley. The bear was Monarch, a huge animal that ranged from Mount Gleason to Chilao (see Robinson 1977:190). The publicity-minded Hearst made good on the bear's name, emblazoning his paper with the motto, "Monarch of the Dailies." Monarch, the bear, arrived in San Francisco Nov. 3, 1889. Hearst wanted to put him on display at the Menagerie (zoo) at Golden Gate Park, but the zoo said no, so Hearst placed him at the Woodwards Gardens, where he opened Nov. 10 to a crowd of more than 20,000. He was later transfered to the zoo, where he lived out his days. Thought to be the largest (formerly) wild California grizzly in captivity at an estimated 1,200 to 1,600 pounds — Kelly says he wasn't weighed — Monarch was used, from life, as the model for the California Bear Flag, which Gov. Hiram Johnson adopted as the official state flag in 1911. (The bear on the original 1846 bear flag was probably a black bear, although it could easily be mistaken for a deformed pig.) That same year, after 22 years in a cage, the aging Monarch was euthanized. His age was unknown; he was already fully mature when captured. His skeleton was immediately transfered to UC Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, where it remains today; his pelt was stuffed and put on display at the Academy of Sciences at Golden Gate Park, where it can still be seen. A couple of final notes: As we said up front, there are lots of tall tales and honest-to-goodness mistakes when it comes to bears. Various Internet sources say Monarch came from the Ojai area; this is incorrect, as Kelly himself tells us. As for Lang's bear, sources indicate it was called the Monarch of the Coast; we don't know if that's accurate, but Lang's bear should not be confused with the (much later) bear named Monarch that modeled for the state flag. Lastly, a word about Chilao: No, it was not one of Tiburcio Vasquez's hideouts. Read Boessenecker 2010.

CHAPTER II. Early in 1889, the editor of a San Francisco newspaper sent me out to catch a Grizzly. He wanted to present to the city a good specimen of the big California bear, partly because he believed the species was almost extinct, and mainly because the exploit would be unique in journalism and attract attention to his paper. Efforts to obtain a Grizzly by purchase and "fake" a story of his capture had proved fruitless for the sufficient reason that no captive Grizzly of the true California type could be found, and the enterprising journal was constrained to resort to the prosaic expedient of laying a foundation of fact and veritable achievement for its self-advertising.

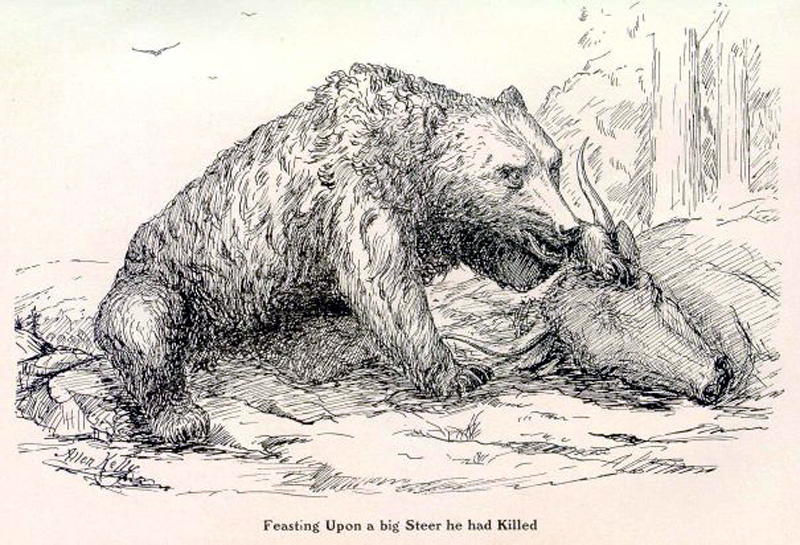

From Santa Paula, I struck into the mountains of Ventura county with an outfit largely composed of information, advice and over-paid assistance. The first two months of the trip were consumed in developing the inaccuracy of most of the information and the utter worthlessness of all the advice and costly assistance, and in acquiring some rudimentary knowledge of the habits of bears and the art of trapping them. Traps were built, under advice, where there was not one chance in a thousand of catching anything, and bogus bear-tracks, made with a neatly-executed model by an ingenious guide, who preferred loafing about camp to moving it, kept the expedition from seeking more promising country. The editor became tired of waiting for his big sensation and ordered me home. I respectfully but firmly refused to go home bearless, and the editor fired me by wire. I fired the ingenious but sedentary assistant, discarded all the advice that had been unloaded upon me by the able bear-liars of Ventura, reduced my impedimenta to what one lone, lorn burro could pack, broke camp and struck for a better Grizzly pasture, determined to play the string out alone and in my own way. The place I selected for further operations was the regular beat of old Pinto, a Grizzly that had been killing cattle on Gen. Beale's range in the mountains west of Tehachepi and above Antelope Valley. Old Pinto was no myth, and he didn't make tracks with a whittled pine foot. His lair was a dense manzanita thicket upon the slope of a limestone ridge about a mile from the spring by which I camped, and he roamed all over the neighborhood. In soft ground he made a track fourteen inches long and nine inches wide, but although at the time I took that for the size of his foot, I am now inclined to think that it was the combined track of front and hind foot, the hind foot "over-tracking" a few inches, obliterating the claw marks of the front foot and increasing the size of the imprint both in length and width. Nevertheless he was a very large bear, and he loomed up formidably in the dusk of an evening when I saw him feasting, forty yards away, upon a big steer he had killed.

I built two stout traps for Pinto's benefit, and day after day I dragged bait around and through the manzanita thickets on the ridge and over all his trails, and sometimes I found tracks so fresh that I was satisfied he had heard me coming and had turned aside. There were cougar and lynx tracks all over the mountains, but I seldom saw the animals and then only got fleeting glimpses of them as they fled out of my way. Many of my prejudices and all my story-book notions about the behavior of the carnivorae were discredited by experience, and I was forced to recognize the plain truth that the only mischievous animal, the only creature meditating and planning evil on that mountain — excepting of course the evil incident to the procurement of food — was a man with a gun. I was the only really dangerous and unnecessarily destructive animal in the woods, and all the rest were afraid of me. After a time, because I had no intention of killing Pinto if I should meet him, I quit carrying a rifle, except when I wanted venison, and tramped all over the mountain in daylight or in darkness without giving much thought to possible encounters. True, I carried a revolver, but that was force of habit mainly, and a six-shooter is company of a sort to a man in the wilderness even if he does not expect to need it. When one has "packed a gun" for years, he feels uncomfortable without it; not because he thinks he has any use for it, but because it has become a part of his attire and its absence unconsciously frets him and sets him wondering vaguely if he has lost his suspenders or forgotten to put on a tie. That the big Grizzly was not quite so audacious and adventurous as he was reputed to be was demonstrated by his suspicious avoidance of the traps while they were new to him, and it became evident that he could not be inveigled into them even by meat and honey until they should become familiar objects to him and he should get accustomed to my scent upon his trails. That I would have caught old Pinto in time there is no doubt, for eventually he was caught in each of the traps, although he escaped through the carelessness of the man who baited and set them. The traps were tight pens, built of large oak logs notched and pinned, roofed and floored with heavy logs and fitted with falling doors of four-inch plank. They were stout enough, and when I saw them ten years later they were sound and fit to hold anything that wears fur, although old Pinto had clawed all the bark off the logs and left deep furrows in them. As a matter of course, all the hunters and mountain men for fifty miles around knew that I was trying to catch a Grizzly, and some of them built traps on their own hook, hoping to catch a bear and make a few dollars. I had encouraged them by promising to pay well for his trouble anybody who should get a bear in his own trap, or find one in any of the numerous traps I had built and send me word. Late in October, I heard that a bear had got into a trap on Gleason Mountain, and leaving Pinto to his own devices, I went over to look at the captive. The Mexican acting as jailor did not know me, and I discovered that Allen Kelly was supposed to be the agent of a millionaire and an "easy mark," who would pay a fabulous sum for a bear. The Mexican assured me that he was about to get wealth beyond the dreams of avarice for that bear from a San Francisco man, meaning said Kelly, whereupon I congratulated him, disparaged the bear and turned to go. The Mexican followed me down the trail and began complaining that the alleged purchaser of the bear was dilatory in closing the deal with cash. He, Mateo, was aggrieved by this unbusinesslike behavior, and it would be no more than proper for him to resent it and teach the man a lesson in commercial manners by selling the bear to somebody else, even to me, for instance. Mateo's haste to get that bear off his hands was evident, but the reason for it was not apparent. Later I understood. Monarch had the bad luck to get into a trap built by a little syndicate of which Mateo was a member. Mateo watched the trap, while the others supplied beef for bait. They were to divide the large sum which they expected to get from me in case they caught a bear before I did, and very likely my fired assistant had a contingent interest in the enterprise. Mateo was the only member of the syndicate on deck when I arrived, and deeming a bird in his hand worth a whole flock in the syndicate bush, he made the best bargain he could and left the others to whistle for dividends. Ten years afterward I met the cattleman who furnished the capital and the beef, and from his strenuous remarks about his Mexican partner I inferred that the syndicate had been deeply disappointed. I also learned for the first time why Mateo was so anxious for me to take the bear off his hands when the evident original purpose was to held me up for a good round sum. The hold-up would have failed, however, because I had spent more than $1,200 and lost five months' time, was nearly broke, did not represent anybody but myself at that stage of my bear-catching career, and for all I knew the editor might have changed his mind about wanting a Grizzly at any price. Finally I consented to take the bear and struck a bargain, and not until money had passed and a receipt was to be signed did Mateo know with whom he was dealing. He paid me the dubious compliment of muttering that I was "un coyote," and as that animal is the B'rer Rabbit of Mexican folk lore, I inferred that the excellent Mateo intended to express admiration for the only evidence of business capacity to be found in my entire career. That dicker for a bear stands out as the sole trade I ever made in which I was not unmistakably and comprehensively "stuck." Mateo was more than repaid for his trouble, however. He helped me build a box, and get the bear into it, and I took Monarch to San Francisco and sold him to the editor of the enterprising paper, who eventually gave him to Golden Gate Park. The newspaper account of the capture of Monarch was elaborated to suit the exigencies of enterprising journalism, picturesque features were introduced where the editorial judgment dictated, and mere facts, such as the name of the county in which the bear was caught, fell under the ban of a careless blue pencil and were distorted beyond recognition. More than one-fourth of Joaquin Miller's "True Bear Stories"' consists of that newspaper yarn, copied verbatim and without amendment, revision or verification. The other three-fourths of the book, it is to be hoped, is at least equally true. Considering all the frills of fiction that were put into the story to make it readable, the careless inaccuracies that were edited into it, and the fact that many persons knew of the preliminary attempts to buy any old bear and fake a capture, it is not strange that people who always know the "inside history" of everything that happens, wag their heads wisely and declare that Monarch was obtained from a bankrupt circus, or is an ex-dancer of the streets sold to the newspaper by a hard-up Italian. But it is incredible that any one who knows a bear from a Berkshire hog could for an instant mistake Monarch for any variety of tamable bear or imagine that any man ever had the hardihood to give him dancing lessons. When Monarch found himself caught in the syndicate trap on Gleason Mountain, he made furious efforts to escape. He bit and tore at the logs, hurled his great bulk against the sides and tried to enlarge every chink that admitted light. He required unremitting attention with a sharpened stake to prevent him from breaking out. For a full week the Grizzly raged and refused to touch food that was thrown to him. Then he became exhausted and the task of securing him and removing him from the trap was begun. The first thing necessary was to make a chain fast to one of his fore-legs. That job was begun at eight o'clock in the morning and finished at six o'clock in the afternoon. Much time was wasted in trying to work with the chain between two of the side logs. Whenever the bear stepped into the loop as it lay upon the floor and the chain was drawn tight around his fore-leg just above the foot, he pulled it off easily with the other paw, letting the men who held the chain fall over backward. The feat was finally accomplished by letting the looped chain down between the roof logs, so that when the bear stepped into it and it was drawn sharply upward, it caught him well up toward the shoulder. Having one leg well anchored, it was comparatively easy to introduce chains and ropes between the side logs and secure his other legs. He fought furiously during the whole operation, and chewed the chains until he splintered his canine teeth to the stubs and spattered the floor of the trap with bloody froth. It was painful to see the plucky brute hurting himself uselessly, but it could not be helped, as he would not give up while he could move limb or jaw. The next operation was gagging the bear so that he could not bite. The door of the trap was raised and a billet of wood was held where he could seize it, which he promptly did. A cord made fast to the stick was quickly wound around his jaws, with turns around the stick on each side, and passed back of his ears and around his neck like a bridle. By that means his jaws were firmly bound to the stick in such a manner that he could not move them, while his mouth was left open for breathing. While one man held the bear's head down by pressing with his whole weight upon the ends of the gag, another went into the trap and put a chain collar around the Grizzly's neck, securing it in place with a light chain attached to the collar at the back, passing down under his armpits and up to his throat, where it was again made fast. The collar passed through a ring attached by a swivel to the end of a heavy chain of Norwegian iron. A stout rope was fastened around the bear's loins also, and to this another strong chain was attached. This done, the gag was removed and the Grizzly was ready for his journey down the mountain. In the morning he was hauled out of the trap and bound down on a rough skeleton sled made from a forked limb, very much like the contrivance called by lumbermen a "go-devil." Great difficulty was encountered in securing a team of horses that could be induced to haul the bear. The first two teams were so terrified that but little progress could be made, but the third team was tractable and the trip down the mountain to the nearest wagon road was finished in four days. The bear was released from the "go-devil" and chained to trees every night; and so long as the camp fire burned brightly he would lie still and watch it attentively, but when the fire burned low he would get up and restlessly pace to and fro and tug at the chains, stopping now and then to seize in his arms the tree to which he was anchored and test its strength by shaking it. Every morning the same old fight had to be fought before he could be tied to his sled. He became very expert in dodging ropes and seizing them when the loops fell over his legs, and considerable strategic skill was required to lasso his paws and stretch him out. In the beginning of these contests the Grizzly uttered angry growls, but soon became silent and fought with dogged persistency, watching every movement of his foes with alert attention and wasting no energy in aimless struggles. He soon learned to keep his hind feet well under him and his body close to the ground, which left only his head and fore-legs to be defended from the ropes. So adroit and quick was the bear in the use of his paws that a dozen men could not get a rope on him while he remained in that posture of defence. But when two or three men grasped the chain that was around his body and suddenly threw him on his back, all four of his legs were in the air at once, the riatas flew from all directions and he was vanquished.

Monarch is the largest bear in captivity and a thoroughbred Californian Grizzly. No naturalist needs a second glance at him to classify him as Ursus Horribilis. He stands four feet high at the shoulder, measures three feet across the chest, 12 inches between the ears and 18 inches from ear to nose, and his weight is estimated by the best judges at from 1200 to 1600 pounds. He never has been weighed. In disposition he is independent and militant. He will fight anything from a crowbar to a powder magazine, and permit no man to handle him while he can move a muscle. And yet when he and I were acquainted — I have not seen him since he was taken to Golden Gate Park — he was not unreasonably quarrelsome, but preserved an attitude of armed neutrality. He would accept peace offerings from my hand, taking bits of sugar with care not to include my fingers, but would tolerate no petting. Within certain limits he would acknowledge an authority which had been made real to him by chains and imprisonment, and reluctantly suspend an intended blow and retreat to a corner when insistently commanded, yet the fires of rebellion never were extinguished and it would have been foolhardy to get within effective reach of his paw. To strangers he was irreconcilable and unapproachable. Monarch passed three or four years in a steel cell before he was taken to the Park. He devoted a week or so to trying to get out and testing every bar and joint of his prison, and when he realized that his strength was over-matched, he broke down and sobbed. That was the critical point, and had he not been treated tactfully by Louis Ohnimus, doubtless the big Grizzly would have died of nervous collapse. A live fowl was put before him after he had refused food and disdained to notice efforts to attract his attention, and the old instinct to kill was aroused in him. His dulled eyes gleamed green, a swift clutching stroke of the paw secured the fowl. Monarch bolted the dainty morsel, feathers and all, and his interest in life was renewed with the revival of his savage propensity to slay. From that moment he accepted the situation and made the best of it. He was provided with a bed of shavings, and he soon learned the routine of his keeper's work in removing the bed. Monarch would not permit the keeper to remove a single shaving from the cage if a fresh supply was not in sight. He would gather all the bedding in a pile, lie upon it and guard every shred jealously, striking and smashing any implement of wood or iron thrust into the cage to filch his treasure. But when a sackful of fresh shavings was placed where he could see it, Monarch voluntarily left his bed, went to another part of the cage and watched the removal of the pile without interfering. In intelligence and quickness of comprehension, the Grizzly was superior to other animals in the zoological garden and compared not unfavorably with a bright dog. It could not be said of him, as of most other animals, that man's mastery of him was due to his failure to realize his own power. He knew his own strength and how to apply it, and only the superior strength of iron and steel kept him from doing all the damage of which he was capable. The lions, for example, were safely kept in cages which they could have broken with a blow rightly placed. Monarch discovered the weak places of such a cage within a few hours and wrecked it with swift skill. When inveigled into a movable cage with a falling door, he turned the instant the door fell, seized the lower edge and tried to raise it. When placed in a barred enclosure in the park, he began digging under the stone foundation of the fence, necessitating the excavation of a deep trench and the emplacement therein of large boulders to prevent his escape. Then he tried the aerial route, climbed the twelve foot iron palings, bent the tops of inch and a half bars and was nearly over when detected and pushed back.

Mr. Ernest Thompson Seton saw Monarch and sketched him in 1901, and he said: "I consider him the finest Grizzly I have seen in captivity." Note. — Without doubt the largest captive grizzly bear in the world, may be seen in the Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. As to his exact weight, there is much conjecture. That has not been determined, as the bear has never been placed on a scale. Good judges estimate it at not far from twelve hundred pounds. The bear's appearance justifies that conclusion. Monarch enjoys the enviable distinction of being the largest captive bear in the world. — N.Y. Tribune, March 8, 1903.

CHAPTER XVII. For several years a large Grizzly roamed through the rugged mountain's in the northern part of Los Angeles county, raiding cattle ranges and bee ranches and occasionally falling afoul of a settler or prospector. He was at home on Mt. Gleason, but his forays took in Big Tejunga and extended for twenty or thirty miles along the range. Every settler knew the bear and had a name for him, and he went by as many aliases as a burglar in active practice. As his depredations ceased after the capture of Monarch in 1889, those who assert that Monarch was the wanderer of the Sierra Madre and Big Tejunga may be right, and some of the stories told about him may be true. Jeff Martin, a cattleman, who lived in Antelope Valley, and drove his stock into the mountains in summer, had several meetings with the big bear, but never managed to get the best of him. When the Monarch didn't win, the fight was a draw. Jeff had an old buckskin horse that would follow a bear track as readily as a burro will follow a trail, and could be ridden up to within a few yards of the game. Jeff and the old buckskin met the Monarch on a trail and started a bear fight right away. The Monarch, somewhat surprised at the novel idea of a man disputing his right of way, stood upright and looked at Jeff, who raised his Winchester and began working the lever with great industry. Jeff was never known to lie extravagantly about a bear-fight, and when he told how he pumped sixteen forty-four calibre bullets smack into the Monarch's shaggy breast and never "fazed" him, nobody openly doubted Jeff's story. He said the Monarch stood up and took the bombardment as nonchalantly as he would a fusilade from a pea-shooter, appearing to be only amazed at the cheek of the man and the buckskin horse. When Jeff's rifle was empty, he turned and spurred his horse back down the trail, followed by the bear, who kept up the chase about a mile and then disappeared in the brush. Jeff's theory was that the heavy mass of hair on the bear's breast effectually protected him from the bullets, which do not have great penetrating power when fired from a forty-four Winchester with a charge of only forty grains of powder. About a week after that adventure the Monarch called at Martin's summer camp on Gleason Mountain to get some beef. It was about midnight when he climbed into the corral. The only beef in the corral that night was on the bones of a tough and ugly bull, and as soon as the Monarch dropped to the ground from the fence he got into trouble. The bull was spoiling for a fight, and he charged on the bear without waiting for the call of time, taking him amidships and bowling him over in the mud before the Monarch knew what was coming. Jeff was aroused by the disturbance and went over to see what was up. He saw two huge bulks charging around in the corral, banging up against the sides and making the dirt fly in all directions, and he heard the bellowing of the old bull and the hoarse growls of the bear. They were having a strenuous time all by themselves, and Jeff decided to let them fight it out in their own way without any interference. Returning to the cabin, he said to his son Jesse and an Indian who worked for him: "It's that d——d old Grizzly having a racket with the old bull, but I reckon the bull is old enough to take care of himself. We'll bar the door and let 'em go it." So they barred the door and listened to the sounds of the battle. In less than a quarter of an hour the Monarch got a beautiful licking and concluded that he didn't want any beef for supper. The bull was tough, anyway, and he would rather make a light meal off the grub in the cabin. Jeff heard a great scratching and scrambling as the Monarch began climbing out of the corral. Then there was a roar and a rush, a heavy thud as the bull's forehead struck the Monarch's rear elevation, a growl of pain and surprise and the fall of half a ton or more of bear meat on the ground outside of the corral. "I reckon the old bull has made that cuss lose his appetite," chuckled Jeff. "He won't come fooling around this ranch any more. I'll bet he's the sorest bear that ever wore hair." The three men in the cabin were laughing and enjoying the triumph of the bull when "whang!" came something against the door, and they all jumped for their guns. It was the discomfited but not discouraged Monarch breaking into the cabin in search of his supper. With two or three blows of his ponderous paw the grizzly smashed the door to splinters, but as he poked his head in he met a volley from two rifles and a shotgun. He looked at Jeff reproachfully for the inhospitable reception, turned about and went away, more in sorrow than in anger. Jeff Martin's next meeting with the Monarch was in the Big Tejunga. He and his son Jesse were hunting deer along the side of the canyon, when they saw a big bear in the brush about a hundred yards up the hill. Both fired at the same moment and one ball at least hit the bear. Uttering a roar of pain, the grizzly snapped viciously at his shoulder where the bullet struck, and as he turned his head he saw the two hunters, who then recognized the Monarch by his huge bulk and grizzled front. The Monarch came with a rush like an avalanche down the mountain side, breaking through the manzanita brush and smashing down young trees as easily as a man tramples down grass. His lowered head offered no fair mark for a bullet, and he came on with such speed that only a chance shot could have hit him anywhere. Jeff and his son Jess did not try any experiments of that kind, but dropped their rifles and shinned up a tree as fast as they could. They were none too rapid, as Jeff left a piece of one bootleg in the Monarch's possession. The Monarch was not a bear to fool away much time on a man up a tree, and as soon as he discovered that the hunters were out of reach he went away and disappeared in the brush. The two men came down, picked up their guns and decided to have another shot at the Monarch if they could find him. They knew better than to go into the brush after a bear, but they hunted cautiously about the edges for some time. They were sure that the Monarch was still in there, but they could not ascertain at what point. Jeff went around to windward of the brush patch and set fire to it, and then joined Jess on the leeward side to watch for the reappearance of the Monarch. The wind was blowing fresh up the canyon and the fire ran rapidly through the dry brush, making a thick smoke and great noise. When the Monarch came out he came rapidly and from an unexpected quarter, and the two hunters had just time enough to break for their tree again and get out of reach. This time the Monarch did not leave them. He sat down at the foot of the tree and watched with malicious patience. The wind increased and the fire spread on all sides, and in a few minutes it became uncomfortably warm up the tree. The bear kept on the side of the tree opposite the advancing fire and waited for the men to come down. Jeff and Jess got a little protection from the heat by hugging the leeward side of the trunk, but it became evident that the tree would soon be in a blaze, and unless they jumped and ran within the next minute or two they would be surrounded by fire. They hoped that the Grizzly would weaken first, but he showed no signs of an intention to leave. When the flames began crawling up the windward side of the tree and the heat became unbearable, Jeff said: "Jess, which would you rather take chances on, Grizzly or fire?" "Dad, I think I'll chance the bear," replied Jess, covering his face with his arm. "All right. When I say go, jump and run as though you were scooting through hell with a keg of powder under your arm." Jeff and Jess crawled out on the limbs and swung by their hands for a moment, and at the word they dropped to the ground within ten feet of the bear and lit out like scared wolves. They broke right through the burning brush, getting their hair singed as they went. The bear started after them, but he was afraid to go through the fire, and while he was finding a way out of the circle of burning brush and timber, Jeff and Jess struck out down the mountain side, making about fifteen feet at a jump, and never stopped running until they got to the creek and out of the bear's sight.

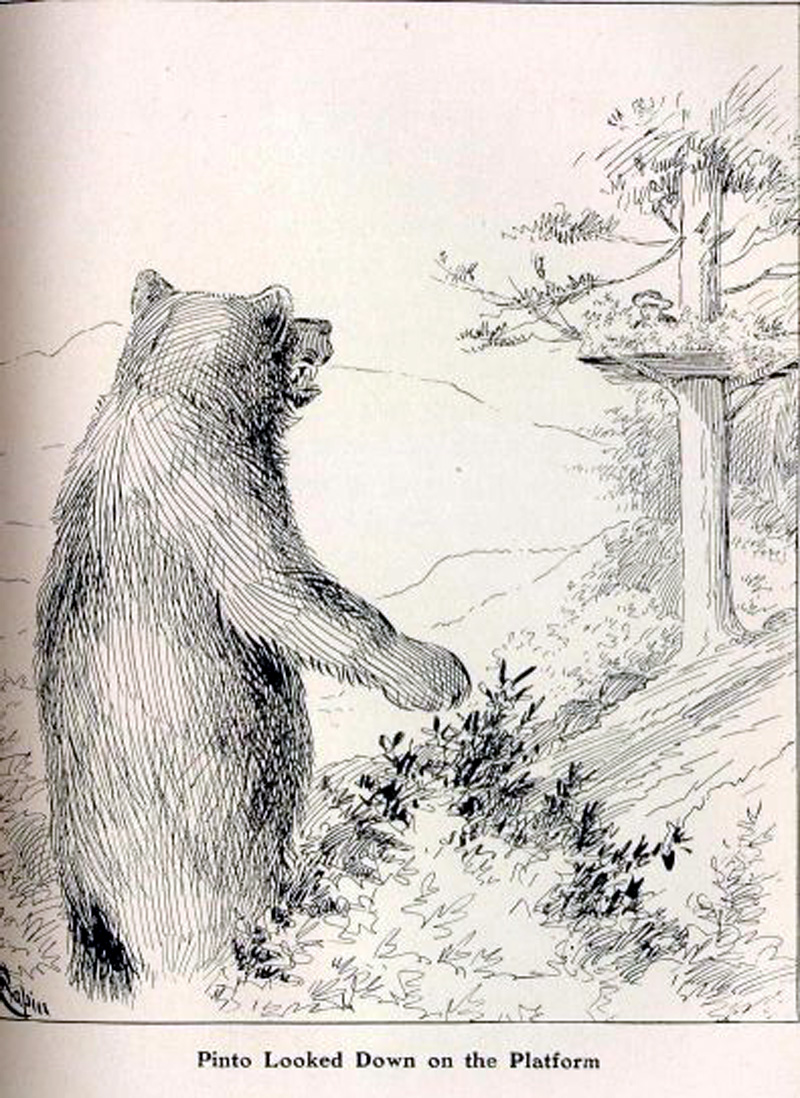

CHAPTER XVIII. This is an incredible bear story, but it is true. George Gleason told it to a man who knew the bear so well that he thought the old Pinto Grizzly belonged to him and wore his brand, and as George is no bear hunter himself, but is a plain, ordinary, truthful person, there is not the slightest doubt that he related only the facts. George said some of the facts were incredible before he started in. He had never heard or read of such tenacity of life in any animal. But there are precedents, even if George never heard of them. The vitality of the California Grizzly is astonishing, as many a man has sorrowful reason to know, and the tenacity of the Old Pinto's hold on life was remarkable, even among Grizzlies. This Pinto was a famous bear. His home was among the rocks and manzanita thickets of La Liebra Mountain, a limestone ridge southwest of Tehachepi that divides Gen. Beale's two ranches, Los Alamos y Agua Caliente and La Liebra, and his range was from Tejon Pass to San Emigdio. His regular occupation was killing Gen. Beale's cattle, and the slopes of the hills and the cienegas around Castac Lake were strewn with the bleached bones of his prey. For twenty years that solitary old bear had been monarch of all that Gen. Beale surveyed — to paraphrase President Lincoln's remark to Surveyor-General Beale himself — and wrought such devastation on the ranch that for years there had been a standing reward for his hide. Men who had lived in the mountains and knew the old Pinto's infirmity of temper were wary about invading his domains, and not a vaquero could be induced to go afoot among the manzanita thickets of the limestone ridge. The man who thought he owned the Pinto followed his trail for two months many years ago and learned many things about him; among others that the track of his hind foot measured fourteen inches in length and nine inches in width; that the hair on his head and shoulders was nearly white; that he could break a steer's neck with a blow of his paw; that he feared neither man nor his works; that while he would invade a camp with leisurely indifference, he would not enter the stout oak-log traps constructed for his capture; and finally, that it would be suicide to meet him on the trail with anything less efficient than a Gatling gun. Old Juan, the vaquero, who lived in a cabin on the flat below the alkaline pool called Castac Lake, was filled with a fear of Pinto that was akin to superstition. He told how the bear had followed him home and besieged him all night in the cabin, and he would walk five miles to catch a horse to ride two miles in the hills. To him old Pinto was "mucho diablo," and a shivering terror made his eyes roll and his voice break in trembling whispers when he talked of the bear while riding along the cattle trails. Once upon a time an ambitious sportsman of San Francisco, who wanted to kill something bigger than a duck and more ferocious than a jackrabbit, read about Pinto and persuaded himself that he was bear-hunter enough to tackle the old fellow. He went to Fort Tejon, hired a guide and made an expedition to the Castac. The guide took the hunter to Spike-buck Spring, which is at the head of a ravine under the limestone ridge, and showed to him the footprints of a big bear in the mud and along the bear trail that crosses the spring. One glance at the track of Pinto's foot was sufficient to dispel all the dime-novel day dreams of the sportsman and start a readjustment of his plan of campaign. After gazing at that foot-print, the slaying of a Grizzly by "one well-directed shot" from the "unerring rifle" was a feat that lost its beautiful simplicity and assumed heroic proportions. The man from San Francisco had intended to find the bear's trail, follow it on foot, overtake or meet the Grizzly and kill him in his tracks, after the manner of the intrepid hunters that he had read about, but he sat down on a log and debated the matter with the guide. That old-timer would not volunteer advice, but when it was asked he gave it, and he told the man from San Francisco that if he wanted to tackle a Grizzly all by his lonely self, his best plan would be to stake out a calf, climb a tree and wait for the bear to come along in the night. So the man built a platform in the tree, about ten feet from the ground, staked out a calf, climbed up to the platform and waited. The bear came along and killed the calf, and the man in the tree saw the lethal blow, heard the bones crack and changed his plan again. He laid himself prone upon the platform, held his breath and hoped fervently that his heart would not thump loudly enough to attract the bear's intention. The bear ate his fill of the quivering veal, and then reared on his haunches to survey the surroundings. The man from San Francisco solemnly assured the guide in the morning, when he got back to camp, that when Pinto sat up he actually looked down on that platform and could have walked over to the tree and picked him off like a ripe persimmon, and he thanked heaven devoutly that it did not come into Pinto's head that that would be a good thing to do. So the man from San Francisco broke camp and went home with some new and valuable ideas about hunting Grizzlies, chief of which was the very clear idea that he did not care for the sport.

Pinto was a "bravo" and a killer, a solitary, cross-grained, crusty-tempered old outlaw of the range. What he would or might do under any circumstances could not be predicated upon the basis of what another one of his species had done under similar circumstances. The man who generalizes the conduct of the Grizzly is liable to serious error, for the Grizzly's individuality is strong and his disposition various. Because one Grizzly scuttled into the brush at the sight of a man, it does not follow that another Grizzly will behave similarly. The other Grizzly's education may have been different. One bear lives in a region infested only by small game, such as rabbits, wood-mice, ants and grubs, and when he cannot get a meal by turning over flat rocks or stripping the bark from a decaying tree, he digs roots for a living. He is not accustomed to battle and he is not a killer, and he may be timorous in the presence of man. Another Grizzly haunts the cattle or sheep ranges and is accustomed to seeing men and beasts flee before him for their lives. He lives by the strong arm, takes what he wants like a robber baron, and has sublime confidence in his own strength, courage and agility. He has killed bulls in single combat, evaded the charge of the cow whose calf he has caught, stampeded sheep and their herders. He is almost exclusively carnivorous and consequently fierce. Such a bear yields the trail to nothing that lives. That is why Old Pinto was a bad bear. So long as Pinto remained in his dominions and confined his maraudings to the cattle ranges, he was reasonably safe from the hunters and perfectly safe from the settler and his strychnine bottle, but for some reasons of his own he changed his habits and his diet and strayed over to San Emigdio for mutton. Perhaps, as he advanced in years, the bear found it more difficult to catch cattle, and having discovered a band of sheep and found it not only easy to kill what he needed, but great fun to charge about in the band and slay right and left in pure wanton ferocity, he took up the trade of sheep butcher. For two or three years he followed the flocks in their summer grazing over the vast, spraddling mesas of Pine Mountain, and made a general nuisance of himself in the camps. There have been other bears on Pine Mountain, and the San Emigdio flocks have been harassed there regularly, but no such bold marauder as Old Pinto ever struck the range. Other bears made their forays in the night and hid in the ravines during the day, but Pinto strolled into the camps at all hours, charged the flocks when they were grazing and stampeded Haggin and Carr's merinos all over the mountains. The herders, mostly Mexicans, Basques and Portuguese, found it heart-breaking to gather the sheep after Pinto had scattered them, and moreover they were mortally afraid of the big Grizzly and took to roosting on platforms in the trees instead of sleeping in their tents at night. Worse than all else, the bear killed their dogs. The men were instructed by the boss of the camp to let the bear alone and keep out of his way, as they were hired to herd sheep and not to fight bears, but the dogs could not be made to understand such instructions and persisted in trying to protect their woolly wards. The owners were accustomed to losing a few hundred sheep on Pine Mountain every summer, and figured the loss in the fixed charges, but when Pinto joined the ursine band that followed the flocks for a living, the loss became serious and worried the majordomo at the home camp. So another reward was offered for the Grizzly's scalp and the herders were instructed to notify the Harris boys at San Emigdio whenever the bear raided their flocks. Here is where Gleason's part of the story begins. The bear attacked a band of sheep one afternoon, killed four and stampeded the Mexican herder, who ran down the mountain to the camp of the Harris boys, good hunters who had been engaged by the majordomo to do up Old Pinto. Two of the Harris boys and another man went up to the scene of the raid, carrying their rifles, blankets and some boards with which to construct a platform. They selected a pine tree and built a platform across the lower limbs about twenty feet from the ground. When the platform was nearly completed, two of the men left the tree and went to where they had dropped their blankets and guns, about a hundred yards away. One picked up the blankets and the other took the three rifles and started back toward the tree, where the third man was still tinkering the platform. The sun had set, but it was still twilight, and none of the party dreamed of seeing the bear at that time, but within forty yards of the tree sat Old Pinto, his head cocked to one side, watching the man in the tree with much evident interest. Pinto had returned to his muttons, but found the proceedings of the man up the tree so interesting that he was letting his supper wait.

The hunters returned to their camp, and early next morning they came back up the mountain with three experienced and judicious dogs. They had hunted bears enough to know that Pinto would be very sore and ill-tempered by that time, and being men of discretion as well as valor, they had no notion of trying to follow the dogs through the scrub oak brush. Amateur hunters might have sent the dogs into the brush and remained on the edge of the thicket to await developments, thereby involving themselves in difficulties, but these old professionals promptly shinned up tall trees when the dogs struck the trail. The dogs roused the bear in less than two minutes, and there was tumult in the scrub oak. Whenever the men in the trees caught a glimpse of the Grizzly they fired at him, and the thud of a bullet usually was followed by yells and fierce growlings, for the bear is a natural sort of a beast and always bawls when he is hurt very badly. There is no affectation about a Grizzly, and he never represses the instinctive expression of his feelings. Probably that is why Bret Harte calls him "coward of heroic size," but Bret never was very intimately acquainted with a marauding old ruffian of the range. The hunters in the trees made body shots mostly. Twice during the imbroglio in the brush the bear sat up and exposed his head and the men fired at it, but as he kept wrangling with the dogs, they thought they missed. This is the strange part of the story, for some of the bullets passed through the bear's head and did not knock him out. One Winchester bullet entered an eye-socket and traversed the skull diagonally, passing through the forward part of the brain. A Grizzly's brain-pan is long and narrow, and a bullet entering the eye from directly in front will not touch it. Wherefore it is not good policy to shoot at the eye of a charging Grizzly. Usually it is equally futile to attempt to reach his brain with a shot between the eyes, unless the head be in such a position that the bullet will strike the skull at a right angle, for the bone protecting the brain in front is from two and a half to three inches thick, and will turn the ordinary soft bullet. One of the men did get a square shot from his perch at Pinto's forehead, and the 45-70-450 bullet smashed his skull. The shot that ended the row struck at the "butt" of the Grizzly's ear and passed through the base of the brain, snuffing out the light of his marvelous vitality like a candle. Then the hunters came down from their roosts, cut their way into the thicket and examined the dead giant. Counting the two shots fired the night before, one of which had nearly destroyed a lung, there were eleven bullet holes in the bear, and his skull was so shattered that the head could not be saved for mounting. Only two or three bullets had lodged in the body, the others having passed through, making large, ragged wounds and tearing the internal organs all to pieces. The skin, which weighed over one hundred pounds, was taken to Bakersfield, and the meat that had not been spoiled by bullets was cut up and sold to butchers and others. Estimating the total weight from the portions that were actually tested on the scales, the butchers figured that Pinto weighed 1100 pounds. The 1800 and 2000-pound bears have all been weighed by the fancy of the men who killed them, and the farther away they have been from the scales the more they have weighed. There is no other case on record of a bear that continued fighting with a smashed skull and pulped brains, although possibly such cases may have occurred and never found their way into print. Gleason saw Old Pinto shortly after the fight and examined the head, and there is no reason to doubt his description of the effect of the bullets.

|

List: Ranger Stations & Fire Stations

Brief History of Angeles Natl Forest

Map: San Gabriel Mtns Nat Monument 2014

SCV Area Map 2014

FAQ: San Gabriel Mtns Nat Monument 2014

Video: Monument Signing Ceremony 2014

New Signage 2/18/2015

The Stories of Monarch and Pinto

Mining & Ranching in Soledad Canyon & Antelope Valley (Earle 2003)

Black Cat Mine

1967: Forest Turns 75

(Newhall Ranger Station 1923)

Newhall Ranger Station 1950s

District Map 1953

Cultural Resources: Verizon Facility, Mt. Baldy

Film: The Big Bus 1976

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.

Twenty-five years later, William Randolph Hearst, owner-editor of the San Francisco Examiner, wanted to see one of these menacing poachers of livestock for himself before

all were exterminated.

So in 1889, Hearst sent one of his young reporters, Allen Kelly, to Southern California not to kill a grizzly but to capture one and bring it back to San Francisco,

to be put on display.

Twenty-five years later, William Randolph Hearst, owner-editor of the San Francisco Examiner, wanted to see one of these menacing poachers of livestock for himself before

all were exterminated.

So in 1889, Hearst sent one of his young reporters, Allen Kelly, to Southern California not to kill a grizzly but to capture one and bring it back to San Francisco,

to be put on display.

The assignment was given to me because I was the only man on the paper who was supposed to know anything about bears. Such knowledge as I had, and it was not very extensive, had been acquired on hunting trips, some successful and more otherwise, in the Sierra Nevada and Cascades. I had had no experience in trapping, but I accepted the assignment with entire confidence and great joy over the chance to get into the mountains for a long outing. The outing proved to be much longer than the editor expected, and trapping a bear quite a different matter from killing one.

The assignment was given to me because I was the only man on the paper who was supposed to know anything about bears. Such knowledge as I had, and it was not very extensive, had been acquired on hunting trips, some successful and more otherwise, in the Sierra Nevada and Cascades. I had had no experience in trapping, but I accepted the assignment with entire confidence and great joy over the chance to get into the mountains for a long outing. The outing proved to be much longer than the editor expected, and trapping a bear quite a different matter from killing one.

Pinto had the reputation of being not only dangerous but malevolent, and there were oft told tales of domiciliary visits paid by him at the cabins of settlers, and of aggressive advances upon mounted vaqueros, who were saved by the speed of their horses. Doubtless the bear was audacious in foraging and indifferent to the presence of man, but he was not malevolent. Indeed, I have yet to hear on any credible authority of a malevolent bear, or, for that matter, any other wild animal in North America whose disposition and habit is to seek trouble with man and go out of its way with the deliberate purpose of attacking him. For many weeks I camped by that spring, much of the time alone, and without even a dog, with only a blanket for covering and the heavens for a roof, and my sleep never was disturbed by anything larger than a wood rat. My camp was on one of Pinto's beaten trails, but he abandoned it and passed fifty yards to one side or the other whenever his business took him down that way, and he never meddled with me or mine. One night, as his tracks showed, he came to within twenty feet of my bivouac, sniffed around inquiringly and passed on.

Pinto had the reputation of being not only dangerous but malevolent, and there were oft told tales of domiciliary visits paid by him at the cabins of settlers, and of aggressive advances upon mounted vaqueros, who were saved by the speed of their horses. Doubtless the bear was audacious in foraging and indifferent to the presence of man, but he was not malevolent. Indeed, I have yet to hear on any credible authority of a malevolent bear, or, for that matter, any other wild animal in North America whose disposition and habit is to seek trouble with man and go out of its way with the deliberate purpose of attacking him. For many weeks I camped by that spring, much of the time alone, and without even a dog, with only a blanket for covering and the heavens for a roof, and my sleep never was disturbed by anything larger than a wood rat. My camp was on one of Pinto's beaten trails, but he abandoned it and passed fifty yards to one side or the other whenever his business took him down that way, and he never meddled with me or mine. One night, as his tracks showed, he came to within twenty feet of my bivouac, sniffed around inquiringly and passed on.

Monarch was pretty well worn out when the wagon road was reached, and doubtless enjoyed the few days of rest and quiet that were allowed him while a cage was being built for his further transportation. He made the remainder of the journey to San Francisco by wagon and railroad, confined in a box constructed of inch-and-a-half Oregon pine that had an iron grating at one end. The box was not strong enough to have held him for five minutes had he attacked it as he attacked the trap and as he subsequently demolished an iron-lined den, but I put my trust in the moral influence of the chain around his neck. The Grizzly accepted the situation resignedly and behaved admirably during the whole trip.

Monarch was pretty well worn out when the wagon road was reached, and doubtless enjoyed the few days of rest and quiet that were allowed him while a cage was being built for his further transportation. He made the remainder of the journey to San Francisco by wagon and railroad, confined in a box constructed of inch-and-a-half Oregon pine that had an iron grating at one end. The box was not strong enough to have held him for five minutes had he attacked it as he attacked the trap and as he subsequently demolished an iron-lined den, but I put my trust in the moral influence of the chain around his neck. The Grizzly accepted the situation resignedly and behaved admirably during the whole trip.

He remains captive only because it is physically impossible for him to escape, not because he is in the least unaware of his power or inept in using it. Apparently he has no illusions concerning man and no respect for him as a superior being. He has been beaten by superior cunning, but never conquered, and he gives no parole to refrain from renewing the contest when opportunity offers.

He remains captive only because it is physically impossible for him to escape, not because he is in the least unaware of his power or inept in using it. Apparently he has no illusions concerning man and no respect for him as a superior being. He has been beaten by superior cunning, but never conquered, and he gives no parole to refrain from renewing the contest when opportunity offers.

This is the sort of bear Old Pinto was, eminently entitled to the name that Lewis and Clark applied to his tribe — Ursus Ferox. Of course he was called "Old Clubfoot" and "Reelfoot" by people who did not know him, just as every big Grizzly has been called in California since the clubfooted-bear myth became part of the folk lore of the Golden State, but his feet were all sound and whole. The Clubfoot legend is another story and has nothing to do with the big bear of the Castac.

This is the sort of bear Old Pinto was, eminently entitled to the name that Lewis and Clark applied to his tribe — Ursus Ferox. Of course he was called "Old Clubfoot" and "Reelfoot" by people who did not know him, just as every big Grizzly has been called in California since the clubfooted-bear myth became part of the folk lore of the Golden State, but his feet were all sound and whole. The Clubfoot legend is another story and has nothing to do with the big bear of the Castac.

The man carrying the blankets dropped them and seized a heavy express rifle that some Englishman had left in the country. The other man dropped the extra gun and swung a Winchester 45-70 to his shoulder. The express cracked first, and the hollow-pointed ball struck Pinto under the shoulder. The 45-70 bullet struck a little lower and made havoc of the bear's liver. The shock knocked the bear off his pins, but he recovered and ran into a thicket of scrub oak. The thicket was impenetrable to a man, and there was no man present who wanted to penetrate it in the wake of a wounded Grizzly.

The man carrying the blankets dropped them and seized a heavy express rifle that some Englishman had left in the country. The other man dropped the extra gun and swung a Winchester 45-70 to his shoulder. The express cracked first, and the hollow-pointed ball struck Pinto under the shoulder. The 45-70 bullet struck a little lower and made havoc of the bear's liver. The shock knocked the bear off his pins, but he recovered and ran into a thicket of scrub oak. The thicket was impenetrable to a man, and there was no man present who wanted to penetrate it in the wake of a wounded Grizzly.