|

|

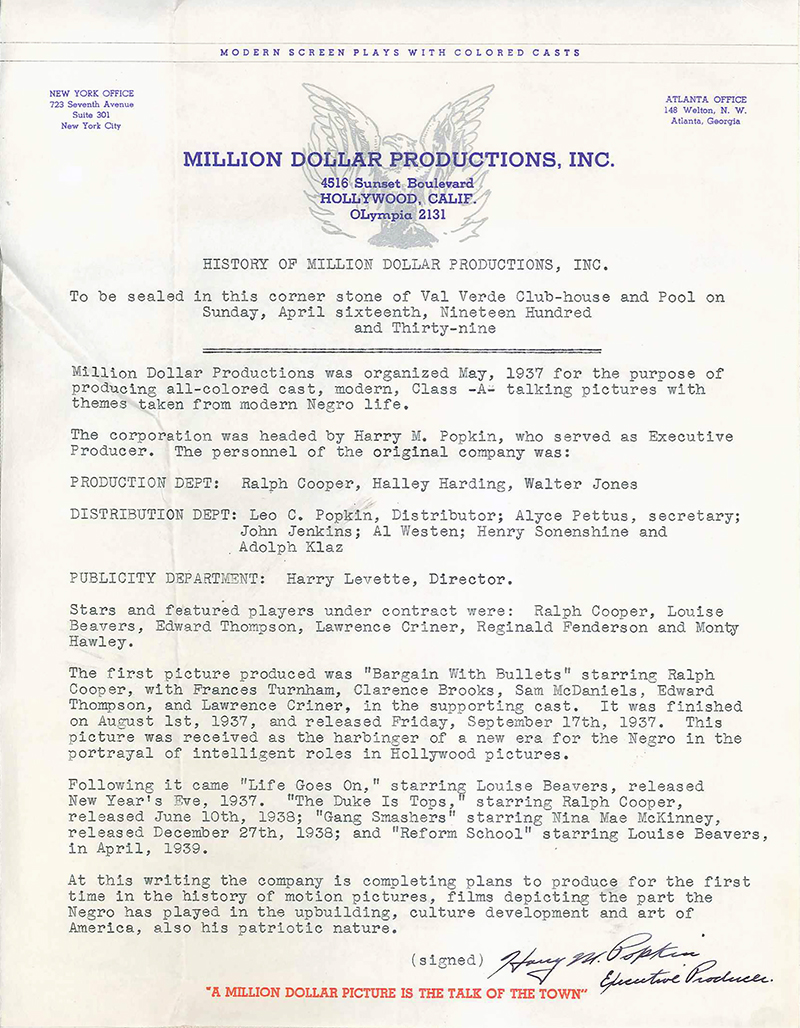

Click image to enlarge

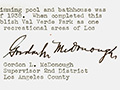

History of Million Dollar Productions Inc., as written (or at least signed) by Harry Popkin. Included in the time capsule that was secreted inside the cornerstone of the Val Verde Park pool house on April 16, 1939. The Los Angeles County Parks Department opened the capsule in 1994 during a renovation project and photographed the contents circa 2014. In 1937, the white Los Angeles theater owner Harry M. Popkin and his movie-producer brother Leo C. Popkin ("D.O.A.," 1950) teamed up with the black actor Ralph Cooper ("Dark Manhattan," 1937) to form Million Dollar Productions. Picking up where the pioneering black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux (1884-1951) left off, Million Dollar "moved black filmmaking away from a marginalized form toward the mainstream, advancing considerably its reputation and ability to attract audiences" (Balio 1993:345). Cooper, who had founded amateur night at the Apollo Theater in Harlem in 1935, had been brought out West by Fox "but was immediately dropped when he didn't fit the desired stereotype" (ibid.:346). Now, Million Dollar would use the crime/gangster genre as a vehicle to make Cooper a star of black cinema. Harry Popkin (1906-1991) was already featuring many African American performers on stage and in film at his Million Dollar Theater at 307 S. Broadway in Los Angeles. Built by Sid Grauman — Grauman's first theater, opening in February 1918 with William S. Hart's "The Silent Man" — Popkin bought the place in 1935. In the 1940s, stage acts ran the integrated gamut from Billie Holliday and Lionel Hampton to Artie Shaw. Popkin leased the premises in 1945 to Metropolitan Theatres, which added it to the Orpheum vaudeville circuit and booked such acts as the Nat King Cole Trio. Around 1949 it was subleased to Frank Fouce, who turned it into a major, long-running Spanish-language film house and Mexican vaudeville theatre. Dolores del Río, José Feliciano, Juan Gabriel and many other luminaries weren't strangers to its stage. Fouce and partners would acquire many media companies in the coming decades, eventually selling them in 1986 for $301 million to Hallmark Cards, which rebranded them as Univision. Million Dollar Productions didn't last all that long — its filmmaking days were over by 1942 — but it created a lasting legacy in 1938 when it paired Cooper with a hitherto-unknown actress in "The Duke is Tops." Nine or 10 months later, when Harry Popkin penned the history that's featured here (photo above, text below), he obviously didn't know what he had. He mentions the long-forgotten film — and its male lead — by name, but he doesn't mention its costar. Her name was Lena Horne. Text of document:

Million Dollar Productions, Inc. HISTORY OF MILLION DOLLAR PRODUCTIONS, INC. To be sealed in this corner stone of Val Verde Club-house and Pool on Sunday, April sixteenth, Nineteen Hundred and Thirty-nine

Million Dollar Productions was organized May, 1937 for the purpose of producing all-colored cast, modern, Class -A- talking pictures with themes taken from modern Negro life. The corporation was headed by Harry M. Popkin, who served as Executive Producer. The personnel of the original company was: PRODUCTION DEPT: Ralph Cooper, Halley Harding, Walter Jones DISTRIBUTION DEPT: Leo C. Popkin, Distributor; Alyce Pettus, secretary; John Jenkins; Al Westen; Henry Sonenshine and Adolph Klaz PUBLICITY DEPARTMENT: Harry Levette, Director. Stars and featured players under contract were: Ralph Cooper, Louise Beavers, Edward Thompson, Lawrence Criner, Reginald Penderson and Monty Hawley. The first picture produced was "Bargain With Bullets" starring Ralph Cooper, with Prances Turnham, Clarence Brooks, Sam McDaniels, Edward Thompson, and Lawrence Criner, in the supporting cast. It was finished on August 1st, 1937, and released Friday, September 17th, 1937. This picture was received as the harbinger of a new era for the Negro in the portrayal of intelligent roles in Hollywood pictures. Following it came "Life Goes On," starring Louise Beavers, released New Year's Eve, 1937. "The Duke Is Tops," starring Ralph Cooper, released June 10th, 1938; "Gang Smashers" starring Nina Mae McKinney, released December 27th, 1938; and "Reform School" starring Louise Beavers, in April, 1939. At this writing the company is completing plans to produce for the first time in the history of motion pictures, films depicting the part the Negro has played in the upbuilding, culture development and art of America, also his patriotic nature. /signed/ Harry M. Popkin, Executive Producer A MILLION DOLLAR PICTURE IS THE TALK OF THE TOWN

More About Million Dollar Productions

Black films grew largely out of an effort to find an independent cinematic voice, one that could rival Hollywood and respond to the prevailing stereotypes. Black filmmaking actually began back in 1910, with shorts made by William Foster in Chicago. Targeting the black middle class and avoiding stereotypes, Foster's success encouraged a number of other companies. [...] The most prolific and tireless voice in black filmmaking during the [1920s] had been Oscar Micheaux. However, by the 1930s, his reputation was diminishing, since he was no longer a pioneer. Many of his early talkies were composed largely as silents, relying on long explanatory intertitles, such as "A Daughter of the Congo" (1930) and "Ten Minutes to Live" (1932). Micheaux's pictures were usually made in around ten days for between $10,000 and $20,000, with local actors, and shot in the New York area, often relying on the homes of friends for sets. Micheaux believed that profits were inevitably limited and hence saw no reason to increase his investment or quality. His productions had increasing trouble finding exhibition as the black press decried the content of his films as well as his often primitive technique. Micheaux's sporadic output of one or two productions annually became clearly weak alongside those of other, similar companies; his fifteen movies in the decade were only a portion of black filmmaking during a period that saw approximately seventy-five black features. The resurgence in black filmmaking in fact coincided with Micheaux's decline. While Micheaux Pictures Corporation of New York had been the pivotal concern of the 1920s, the better representative of the 1930s and beyond was Million Dollar Productions. Million Dollar, more than any other company, moved black filmmaking away from a marginalized form toward the mainstream, advancing considerably its reputation and ability to attract audiences. Although the Million Dollar name belied the firm's assets and budgets, for the first time blacks had substantial control over production in an integrated filmmaking corporation. Million Dollar was the most financially successful such enterprise to date, and the company sponsored a dozen prestigious productions between 1937 and 1940; at least six of these remained in release during the 1940s through one of its successors, Ted Toddy. Million Dollar had its origins in 1936, when performer Ralph Cooper was brought to Hollywood by Fox but was immediately dropped when he did not fit the desired stereotype. Instead, Cooper united with another black, George Randol, to produce and star in "Dark Manhattan" (1937), which successfully adapted the Hollywood gangster formula to the ethnic screen. Cooper then broke with Randol and joined Harry and Leo Popkin to form Million Dollar Pictures. Over the next three years he co-produced and starred in such movies as "Bargain with Bullets/Gangsters on the Loose" (1937), "Gang War/Crime Street" (1939), "The Duke is Tops/Bronze Venus" (1938), and "Am I Guilty?/Racket Doctor" (1940). In addition, Cooper wrote "Gang Smashers/Gun Moll" (1938), "Reform School/Prison Bait" (1938), "Life Goes On/His Harlem Wife" (1938), and "Mr. Smith Goes West" (1940). Cooper, a bandleader, emcee, and musical entertainer, became the first black matinee idol of the movies; his skillful persona won him the appropriate sobriquet "the bronze Bogart." Although his film career was brief, he had an enormous impact, and the black film cycle of the late 1930s was a direct result of the popularity of "Dark Manhattan." Whereas twenty-three black features were made in the seven years 1930-1936, the next four years, 1937-1940, saw over fifty black movies. The Cooper films in particular, and Million Dollar Productions generally, diverged from earlier black films. Narratives and performances were far more plausible than Micheaux's improbable and excessive melodramatics, yet still dealt with black issues. There was no trace of the homegrown aesthetic associated with Micheaux; Million Dollar films were equivalent in terms of style and quality with the better Hollywood B studios, on a par with the contemporary product of Monogram and Republic. For the first time a series of black films, not just a few isolated examples, sustained a polished, solid production style within the norms of classical production. Well-known stars were offered who could appeal to mixed audiences, such as Cooper, Louise Beavers, and Mantan Moreland. Although produced for only about twice as much as a typical Micheaux film, Million Dollar took advantage of a wide array of Hollywood talent, expertise, and equipment to increase production standards. For instance, "Dark Manhattan" was shot at the Grand National studios, a lot with superior facilities to those offered by Fort Lee and the private homes used in the Micheaux efforts. The consistent problems Micheaux and others had in achieving audible recordings, adequate lighting, smooth editing, and acceptable performances had always impeded their appeal to audiences. Indeed, despite the fact that Micheaux so often fell short, his rare exceptions, such as "Lem Hawkins' Confession/Brand of Cain/Murder in Harlem" (1935) and "Birthright" (1939), indicate that his unrealized hope actually was to achieve such standards. Cooper's former partner, George Randol, was only slightly less successful, merging with the brothers Bert and Jack Goldberg to form International Road Shows in Hollywood. They produced a number of films that moved in the same direction as the Million Dollar efforts, without such smooth results. The Randol-Goldberg product included "Broken Strings" (1940), "Double Deal" (1939), "Midnight Shadows" (1939), "Mystery in Swing" (1939), "Paradise in Harlem" (1940), and "Sunday Sinners" (1940). The Goldbergs had previously been associated with black-cast stage productions, and films like "Harlem is Heaven/Harlem Rhapsody" (1932) and "The Unknown Soldier Speaks/The Unknown Soldier" (1934), and they remained active through the 1940s. Another mixed-race company, Hollywood Productions, headed by white director Richard Kahn, turned out "The Bronze Buckaroo" (1938) [starring Herb Jeffries -Ed.], "Harlem Rides the Range" (1939), "Two Gun Man from Harlem" (1939), and "Son of Ingagi" (1940). Together, Micheaux, Paragon, Hollywood Productions, Million Dollar, and International Road Shows were responsible for more than forty features, well over half the black output during the 1930s. Most of the other companies of the period were responsible for only one or two films, tending to be small and focusing on a specific personality or picture; for example, Eddie Green's Sepia Art produced his own two featurettes. The parallel cases of Cooper and Randol, and their separate development with the Popkins and Goldbergs, along with the example of Richard Kahn, indicate the direction of black production. Many of the companies, and certainly the most prolific ones, were neither all black nor all white, but integrated. Most often blacks collaborated in producing capacities, as writers and as leading performers, governing their personas, while whites, more experienced in B filmmaking, co-produced and directed. The cooperative black-white efforts succeeded, both as commercial ventures and in changing black images; Micheaux's one-man operation was hardly the only method.

CP3908: 9600 dpi jpeg from original document on file with the L.A. County Department of Parks and Recreation.

|

SEE ALSO:

Cornerstone Laying Planned for 4-16-1939

Official Program

Developer's Fact Sheet

Supervisor McDonough Letter

Portwig's "Pioneers" Speech

Women's Political Study Club Letter

Bus Driver Payment Stub, 2/1939

Million Dollar Productions

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.