|

|

William S. Hart: The Good Bad Man

[Exerpt from] The Movies:

The Sixty-Year Story of the World of Hollywood and Its Effect on America from Pre-nickelodeon days to the Present.

By Richard Griffith and Arthur Mayer

New York: Bonanza Books, 1957 (pp. 90-96).

|

Webmaster's note.

This essay isn't so much a biography of William S. Hart as it is a dissertation on the persona he created, the "good bad man." Pulling only those bits and pieces from Hart's early life that fit with the thesis, it mirrors the Hart mythos: that Hart knew the West as a boy and depicted it as it really was. The truth is more complex. Yes, the West that Hart portrayed was deeply influenced by his boyhood, but it was influenced by boyhood memories that evolved over time. It's more correct to say Hart's "good bad man" mirrored the impression that the West made on him as a child: a West that was blacker and whiter, more natural and honest, than the East Coast, where he lived most of his first 50 years. Combine his reminiscences with his experience as a Shakespearean actor on Broadway, and you've got the recipe for the Western melodrama. In reality the setting is secondary; the "good bad man" is an outlaw who finds the path of righteousness in the course of saving a damsel from some form of distress but is denied salvation because of his past misdeeds. Melodrama is melodrama wherever it occurs. This essay was written in the 1950s, when most new Westerns were little more than low-budget action pictures. The authors wax nostalgic, terming Hart's films "authentic." One area where Hart brought authenticity was in costuming, back in his stage days. But the authors' assertion that "murder was not a major crime on the prairies and in the Rockies" during the time depicted in Hart's films is a stretch of the imagination, and a telling one. They intend praise when they say, "many of the exteriors in Hart's films have the look of a Brady photograph." The corollary is also true: For Hart, the West was a carefully dressed set where he tried to recapture his lost youth. For a fuller and more insightful biography, read "William S. Hart: Projecting the American West" by Ronald L. Davis (University of Oklahoma Press, 2003).

The Good Bad Man The greatest of all Western stars was also the most authentic. William S. Hart was brought up in the "real" West. Born in Newburgh, New York, he was taken by his father to Minnesota and Wisconsin when those states were still inhabited by the Blackfeet and Sioux who had fought Custer in the Indian wars. At six, the boy Bill could speak Sioux and by the time he reached adolescence he had worked as a ploughboy and ranch hand, learning to protect himself against the deadly dangers of lie in a country where knowledge of the terrain and instant readiness for self-defense were conditions of survival. Before he reached manhood, he had come to think of frontier life as the most natural and healthy, and the frontier code as iron law. When the Harts returned to the East, Bill succumbed to an unaccountable urge to become an actor. From the early 1890s to 1914 he barnstormed the country as leading man to stars like Julia Arthur and Modjeska. Most successful at first in Shakespearean roles, he eventually found his métier in a series of plays of Western life ("The Virginian," "The Squaw Man"). This was greatly to his liking. He enjoyed recreating the experiences of his childhood and instructing Broadway dramatists and thespians in them. But the proscenium was limiting, and when producer Thomas H. Ince invited him to join the famous stage players then trekking to California, he welcomed the chance. When Hart entered films in 1914, the familiar pattern of the Western film had been established by "Broncho Billy" Anderson and indeed appeared to have exhausted its initial popularity. To Hart, this theatrical version of the frontier was ridiculous and unreal. He determined to put the genuine article on the screen, and in the many two-reel films in which he starred for Ince a new portrait of the frontier appeared, and a new protagonist. Two-Gun Bill Hart William S. Hart created his character, the Good Bad Man, out of his own memories and experiences. In the majority of his pictures, he was an outlaw who underwent moral reformation of a kind, yet stayed outside the law. In this he embodied two conflicting tendencies of the Old West. Murder was not a major crime on the prairies and in the Rockies because rudimentary frontier justice, and often life itself, rested on quick trigger fingers. But horse stealing, claim jumping or consorting with the Indians as a "renegade" were despised because they were social crimes — indirect threats to the whole community. Hart, the outlaw, was sympathetic because he always supported the basic code. To his audiences the Good Bad Man was not only sympathetic but an enviable figure. Americans of the early twentieth century had been steeped in the traditions of the frontier and fully understood the sliding-scale morality of the Hart films. The West was opened by men whose tenacity in the face of hardship was matched by a boyish desire for adventure for its own sake. As the new country developed, this latter quality became an anachronism and soon only an outlaw could live what formerly was the normal life of all men on the frontier. In Hart's films, which represent the halfway stage in this transition, the Good Bad Man was still a glamorous character, secretly envied by all who were irked by civilized restraint. But by 1910-1920 he had to meet a tragic end. The characters inside the film might admire him, but the morality of a now settled country could not permit an outlaw to escape scot-free. Probably no such pictures as William S. Hart's Westerns will ever be made again. The formula of today's Western is nearly as stylized as that of Restoration comedy. Its purpose is not to portray a way of life but to gratify the escape impulse once served by dime novels and gaslight melodrama. Hart's films were made not primarily to gratify that impulse. They were produced by a man who understood the frontier code and was able to furnish it out in authentic detail. His pictures were not only more accurate psychologically but achieved much wider and more lasting impact than any subsequent Western film or star can boast. People of all sorts found themselves strangely stirred by the conflict between Hart's behavior and his character. It was a conflict to which they felt linked, a cultural inheritance from the "lost, wild America" of the day before yesterday. Nowhere is Hart's difference from today's conventional Western hero better seen than in his treatment of women and sex. A final clinch may be allowed contemporary cowboys, if the horse is present as a chaperon, but their main concern with their heroines is to rescue them from other men, not for themselves but for the noble cause of virginity. Hart expected all women to be like Louise Glaum, the seductive villainess of many of his films; his relations with them were a working arrangement involving money and sex, no questions asked, no answers given. When to his surprise he encountered innocence in the person of Besssie Love of Margery Wilson, he either ran from them as jail bait or attempted — and often accomplished — seduction, followed by remorse and a tragic death of atonement. There were many tragic endings in Hart's films, unthinkable as that would be today, and Louise Delluc and other European intellectuals were fascinated by their resemblance to the simplicity of classic tragedy, with Louise Glaum as a new Clytemnestra and Miss Love another Electra. The European reception of Westerns was conditioned by the Continental popularity of James Fenimore Cooper, and the French especially thought of Hart and his women as contemporary American types. Despite this confusion of nineteenth- and twentieth-century America, the French were the first to see that the Hart films were epic in style and that their material was truly cinematic. The Real West, Wild and Wooly As audiences responded to Hart's realistic Westerns, he extended their range to include every aspect of the old frontier days he knew and loved. His West was both drab and sinister. It pulsated with menace and passion. Men lied and betrayed and fought and killed. But they also loved and sacrificed. Many of the exteriors in Hart's films have the look of a Brady photograph. The characters in them were hard-bitten desperadoes of every national variety who had come to the frontier for no good. Often they were played by men Hart gathered from the last frontiers of Arizona and the Yukon.

|

WATCH FULL MOVIES

Biography

(Mitchell 1955)

Narrated Biopic 1960

Biography (Conlon/ McCallum 1960)

Biography (Child, NHMLA 1987)

Essay: The Good Bad Man (Griffith & Mayer 1957)

Film Bio, Russia 1926

The Disciple 1915/1923

The Captive God 1916 x2

The Aryan 1916 x2

The Primal Lure 1916

The Apostle of Vengeance (Mult.)

Return of Draw Egan 1916 x2

Truthful Tulliver 1917

The Gun Fighter 1917 (mult.)

Wolf Lowry 1917

The Narrow Trail 1917 (mult.)

Wolves of the Rail 1918

Riddle Gawne 1918 (mult.)

"A Bullet for Berlin" 1918 (4th Series)

The Border Wireless 1918 (Mult.)

Branding Broadway 1918 x2

Breed of Men 2-2-1919 Rivoli Premiere

The Poppy Girl's Husband 3-23-1919 Rivoli Premiere

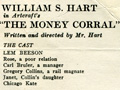

The Money Corral 4-20-1919 Rialto Premiere

Square Deal Sanderson 1919

Wagon Tracks 1919 x3

Sand 1920 Lantern Slide Image

The Toll Gate 1920 (Mult.)

The Cradle of Courage 1920

The Testing Block 1920:

Slides, Lobby Cards, Photos (Mult.)

O'Malley/Mounted 1921 (Mult.)

The Whistle 1921 (Mult.)

White Oak 1921 (Mult.)

Travelin' On 1921/22 (Mult.)

Three Word Brand 1921

Wild Bill Hickok 1923 x2

Singer Jim McKee 1924 (Mult.)

"Tumbleweeds" 1925/1939

Hart Speaks: Fox Newsreel Outtakes 1930

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.