|

|

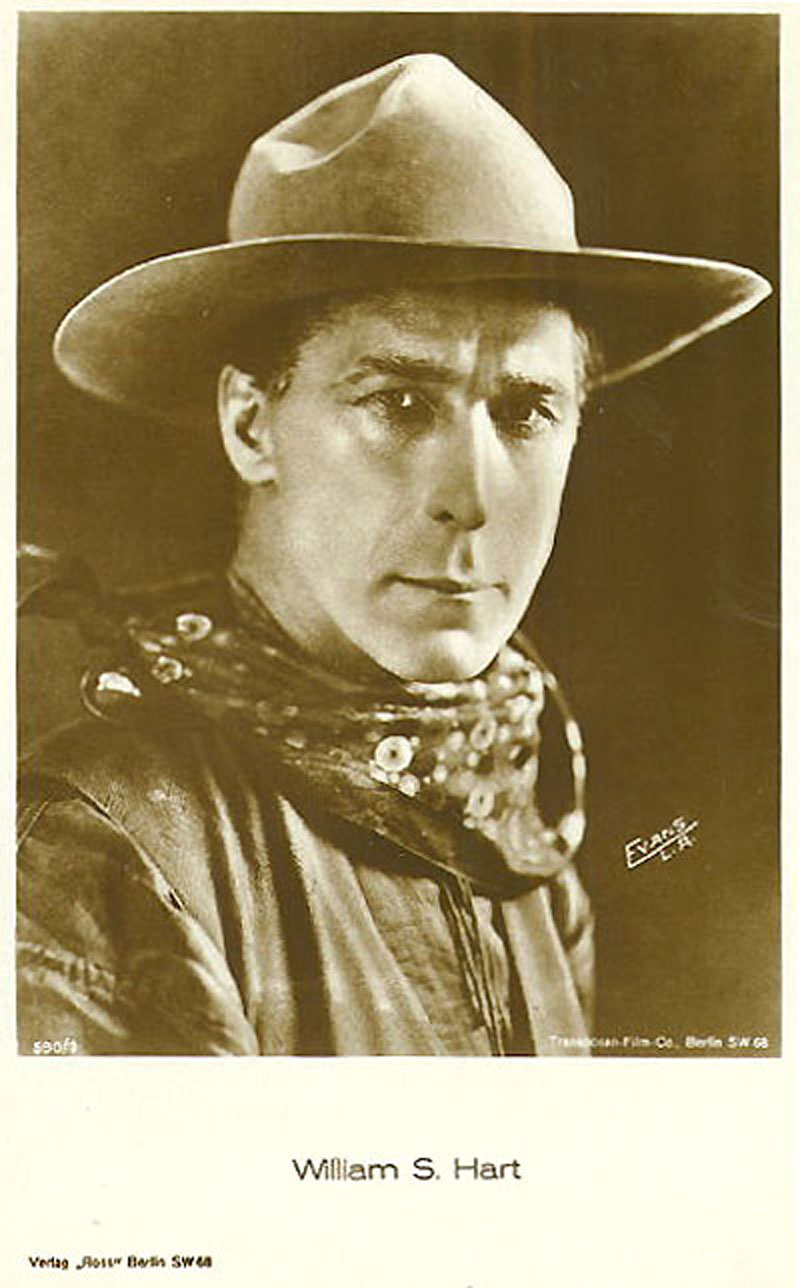

William S. 'Bill' Hart.

By PETE LA ROCHE

©True West magazine, June 1971

Click image to enlargeA tall, lean man sat his cow pony with an ease that attested to his many years in the saddle; his gray eyes surveyed a static scene that within minutes would erupt into a wild, roaring hell-bent-for-action sequence that would make motion picture history.

The year was 1925. The scene in question would be the highlight of the motion picture, "Tumbleweeds." And the man who sat the cow pony was the producer, director and star of the picture — William S. Hart.

At 56 years of age*, William Surrey Hart was about to take off on a dangerous four-hour ride that would entail spills, jumps and the need for three changes of horses to carry him through to victory. And all of this under a hot desert sun. By today's standards of picture making, Hart's decision to make this grueling ride would be looked upon as ridiculous, even by men half his age. Today all of it would be filmed with a double while the studio's valuable property star would be sitting in the shade probably sipping a tall, cool one.

This is not to say that all of today's stars are unable to perform the dangerous stunts which are written into the script. John Wayne, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, Lee Marvin and a few others are fully capable of meeting any demands; but their studios wouldn't allow it if a double or trick photography could make a passable substitute.

In the earlier days of picture making, a star took great pride in his image of a two-fisted, red-blooded hero, and at the risk of his life performed all of his stunts himself. As a result, some of the classics of the silent screen have never been surpassed in realism by the modern movie maker.

One such was the filming in 1914 of "The Spoilers," a great story of the North by Rex Beach, starring William Farnum and Tom Santschi. The picture's fight scene lasted through one full reel and was the granddaddy of them all. All subsequent filmings of "The Spoilers" — 1922, with Milton Sills and Noah Beery; 1930 with Gary Cooper and William Boyd; 1942 with John Wayne and Randolph Scott — were somewhat "stagy" affairs. In some of them the use of stunt men was evident. The later versions also employed breakaway furniture and basted clothing that came apart readily, both of which were unknown or were frowned upon in the earlier era. In the original filming, Farnum and Santschi struck, clawed and tore at each other with such realism that it left no doubt in the mind of the view that this was a fight to the finish.

* * * William S. Hart spent most of his early life in Minnesota and the Dakotas when that part of the United States was still the frontier and inhabited by the Blackfeet and Sioux. He knew the West and the ways of the Westerners.

After some years on the stage in New York, he came west at the insistence of his friend Thomas Ince, then a major producer of the early silents. At that time the sort of Western movie produced by (and starring) Broncho Billy Anderson — two-reelers with hackneyed stories and action — was definitely on the wane.

When Hart arrived in Hollywood in 1914, he agreed to do Westerns, but only after being assured that he could do them as he knew the West, its men and action. He was determined to put the real article on the screen, and in his very first production a new and indestructible life for the Western began.

Hart's sets were basic, the way the early towns of the West had been — dusty, dirty, ramshackle. His actors were dressed realistically, not for show. Hart himself played a character of his own creation, the "good" badman, drawn from his memories and experiences of the earlier West.

So well did he establish this character, and what was later called "the documentary-like realism" of his Westerns, that French movie critic Louis Delluc wrote: "I think that Rio Jim (as he was called in France) is the first real figure established by the cinema. And his settings are so real that they must be filmed in existing communities."

Bill Hart's films supported the basic code of the early West. Murder was not a major crime on the early frontier because frontier justice and very often life itself rested on a quick trigger finger. But claim-jumping, horse stealing and going over to the Indians as a renegade were considered social crimes and a threat to the whole community.

So while Hart cinematically fought, killed, drank and gambled, he made sure that he never committed a social crime. In most of his films, he was reformed by the "good" girl after having shown (in a time of crisis) that there was a basic goodness in his own character.

As for sex in his films, Louise Glaum usually played the seductive gal who made no bones about what she was selling, and Hart paid for it, no questions asked. This was an authentic part of the frontier town, and Bill Hart did not leave it out. This was the era of the "man," and his wants were not denied or restricted. Hart made this plain in all his films. Saloons were there. Gambling went on around the clock, and the ever-present dancehall girls were around to please, entertain and satisfy.

* * * While women were a precious item on the frontier, they were not regarded as highly destructible and fragile as the woman of today. Hart was truthful in the handling of his women. He was gentle to the gentlewoman who, in his films, represented what was fine in womanhood, but he was hard in dealing with the kind who aroused his wrath.

A notable example of this treatment was vividly displayed in his film of 1916, "Hell's Hinges." While he was against a young minister's establishing a church in the town of Hell's Hinges, he respected him for attempting to carry out his mission in the face of strong opposition. And when Louise Glaum, the town's foremost Lady of Joy, seduced the young minister after having plied him with whiskey, Hart broke in on her and thoroughly manhandled her.

From the 1930s on, Westerns deteriorated, eventually becoming nothing more than film far for children. They leaned heavily on gaudy outfits, flashy horses with silver trapping, the sterile hero, and his equally sexless female companion.

It is quite understandable that to a man with Hart's ability to film the lusty, true West, these demands for the gutless, sexless wonders caused him to withdraw from picture making after 12 years as the undisputed king of the cowboy stars.

Hart's success derived from the fact that by 1920 the West of the frontier days was fast disappearing. Territoried had become states, and Indians were on reservations. Highways crisscrossed this vast land and large areas were being set aside for parks. Nostalgia for the lusty life of the daring, fighting man of the West filled the movie houses.

Hart not only portrayed this person but was, to a great extent, the man he played. He was an expert horseman, well capable of taking care of himself in physical combat.

His pinto, Fritz, was the most famous horse in the world. At one time there was a "Fritz" club (everyone belonging had to own a pinto), and by 1921 the club had 11,000 members. One member was a Moroccan price who had imported two pintos from North Dakota. Fritz is buried at the William S. Hart ranch in Newhall, Calif., his memory commemorated by a suitable monument.

Soon after Hart arrived in Hollywood he found living in the city too restrictive. He needed the outdoors, a place where he could keep his horses, ride, shoot and have the freedom he had known as a boy on the prairies. One day on location he found exactly what he wanted: beautiful rolling acres under a clear, sunny sky, with a high point which was perfectly suited for a great ranch house. He bought the land and laid out his spread soon after — barns, corrals, riding trails and finally the great ranch house on the hill.

The rough schedule of making dozens of pictures a year was highly demanding of his energy, and Hart stayed in trim by living a simple life. If there was no shooting schedule for that day he usually spent hours in the saddle, riding his ranch, helping with the many chores and attending tot the business of running a ranch.

* * * While Hart's movies were "Western," it would be a mistake to casually dismiss them as such. Joe Franklin in his Classics of the Silent Screen says of "Hell's Hinges," Hart's film of 1916, "This film more closely resembled the Swedish The Atonement of Gosta Berling or Somerset Maugham's Rain than it does the traditional Western..."

Not only did Hart star in "Hell's Hinges," he directed it. Critics of the day lauded Hart on his directorial capabilities and wondered why his talent in this line had gone unrecognized so long. Camera placements, the handling of mob scenes, and the final burning of Inceville, which was cleverly filmed to symbolize the Inferno, led the French critic Jean Cocteau to write: "M. Ince may be pround of himself for allowing M. Hart to create such a spectacle as this which seems in recollection to equal the world's greatest literature."

And so, while Hart's films were Westerns, the stories could have been adapted to almost any locale. Each film contained a story dealing with people — their loves, hates, ambitions and sorrows. He insisted on a strong story; then it was adapted to the Western setting, and in the process, the finished product benefited from the colorful West and its singular breed of people.

Then the early 1920s began tolling a faint knell for the William S. Hart productions. A new type of Western had appeared on the scene, and a new type of cowboy hero. The new idol appeared in the form of Tom Mix, who gave the Western showmanship, color and excitement. And no one has ever quite equaled him in these categories.

As early as 1921, film makers and distributors were warning Hart to change, but Bill paid them no heed and continued making films his own way. With the advent of Tom Mix and Hoot Gibson, his movies returned less and less revenue, and when Paramount asked him to turn over the production of his movies to someone else, he refused and left the studio.

Then in 1925 he made his most ambitious film — "Tumbleweeds." It was to be his last. When the picture was less successful at the box office than he had expected, Hart was convinced that moviegoers were no longer interested in realism and an honest portrayal of the great West. He retired to his ranch in Newhall.

Approaching 60, he was a little tired, and there was a great deal that he wanted to put down on paper.

On June 23, 1946, William S. Hart died, leaving behind a collection of motion pictures that will live not just as Westerns, but as fine films — films which opened the door to the vast, colorful panorama of an exciting land and its exciting people in an era that had just slipped over the horizon.

This assumes Hart was born in 1870, which is how his birth year was commonly reported during the actor's lifetime. The accepted year today is 1864 (Dec. 6), making him 60 during most of 1925.

©1971 TRUE WEST/WESTERN PUBLICATIONS · REPRINTED BY PERMISSION

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.