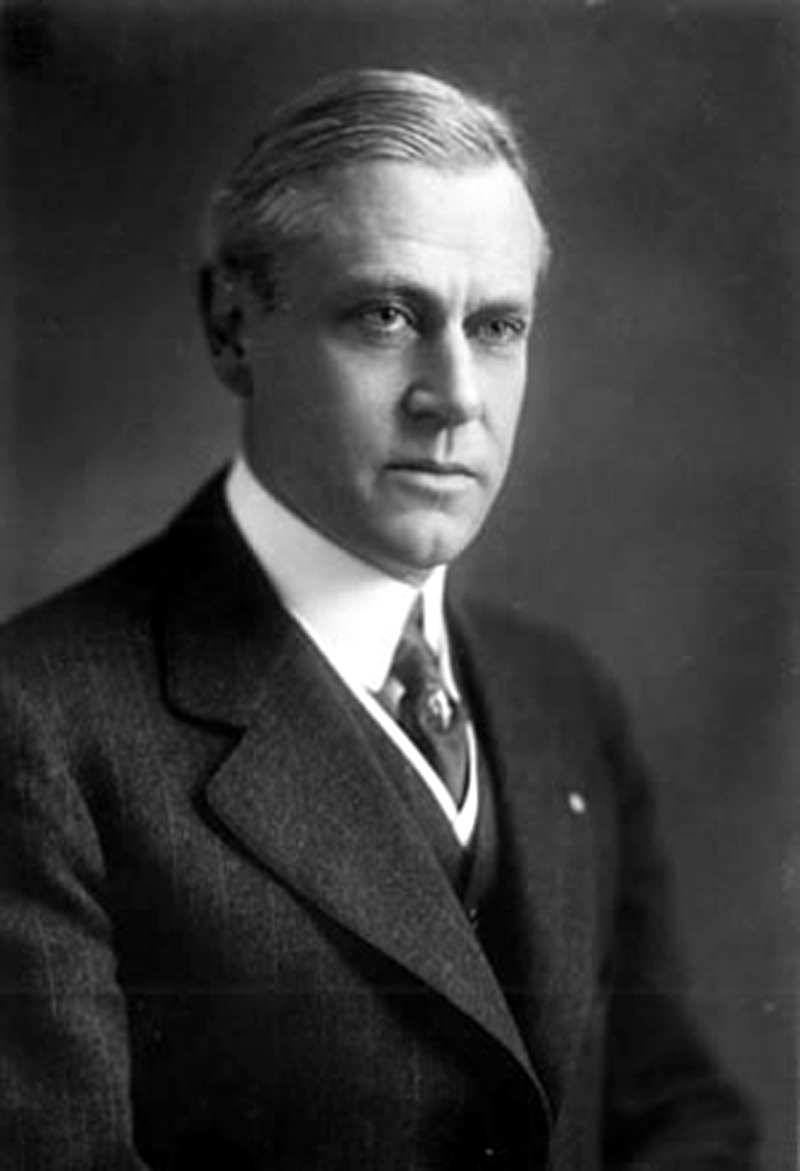

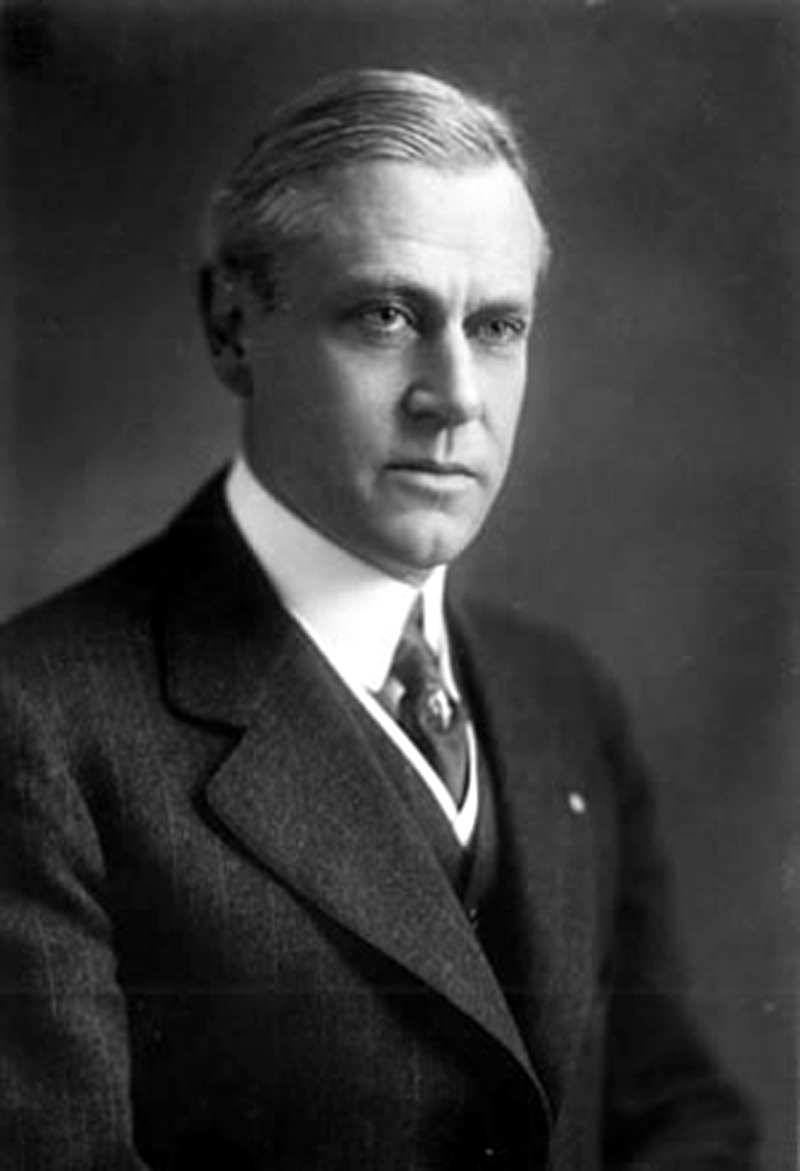

Stephen T. Mather in 1916

|

During the middle of the nineteenth century California experienced a vast influx of new residents, many of whom were driven by the desire to strike it rich by discovering a vast fortune in gold mineral deposits or the "black gold" of oil. Another "gold," considered by some as "white gold" and perhaps not as well known as the first two, existed in the form of a mineral by the name of borax. Borax, boric acid, and other compounds of boron were utilized a century ago for everything ranging from medicinal purposes, food preservation, glass blowing, cleaning and even personal grooming. Several fortunes were built in the borax mining industry and the wealth it generated plays a prominent role in our state and local history. This is where the partnership of two very dissimilar men come into play.

|

Timeline

1898 — Thorkildsen, of Chicago, leaves Pacific Coast Borax, uses $17,000 life savings to purchase borax mine on Frazier Mountain.

1898 — Mather, still at Pacific Coast Borax in Chicago, becomes president of new Thorkildsen-Mather Borax Co.

1904 — Mather leaves Pacific Coast Borax, joins Thorkildsen at Frazier Mountain, which is about tapped out.

1905 — Thorkildsen buys claim to borax (Colemanite) deposit in Tick Canyon for $80,000.

1905 — Thorkildsen-Mather Co. renamed Sterling Borax Co.

1908 — Tick Canyon mine is operational; annual profit of $500,000.

1911 — Pacific Coast Borax buys Sterling Borax Works from Mather and Thorkildsen for $1.8 million; PCB operats Sterling Borax as separate division with Thorkildsen as president and Mather as vice president.

1913 — Pacific Coast Borax chief Francis Marion "Borax" Smith is financially overextended; relinquishes assets to creditors. Pacific Coast Borax eventually absorbed into U.S. Borax.

1921 — Sterling Borax Works shuttered; equipment shipped to borax works in Ryan, Nev.

— SCVHistory.com

|

Stephen T. Mather is best known as the founder of the National Park Service. He is certainly very deserving of all the accolades he has received. Without his influence, the public may have never been afforded the opportunity to explore the vast beauty of our nation's wilderness areas. It is unlikely that the National Park Service would have ever been founded, at least not under Mather's leadership, had it not been for the personal wealth he generated with borax. Borax allowed Mather the time and resources to focus his attention on matters that were dear to his heart. The mining industry was only his vehicle. Mather's passion was public service and his vision was to preserve our nation's natural beauty, providing every citizen access to explore America's abundant sanctuaries of nature.

Mather family roots in America trace back to Richard Mather, a clergyman during the time of the Pilgrim Fathers. Of the five sons born to Richard Mather, only one resisted the call to serve in the pulpit. This was Timothy. He elected to become a farmer and by chance, fathered the Mather clan's only male offspring, thus continuing the family name. The subsequent generations, most notably the Reverend Dr. Moses Mather and his son, Deacon Joseph Mather, settled into what was to become the Mather Homestead in Darien, Connecticut, owned to this day by the Mather family. Of the forty-five grandchildren born to Deacon Joseph, one was Stephen's father, Joseph Wakeman Mather, born in 1820.

Joseph W. Mather, was a remarkably resilient man with deep convictions and diverse talents. Aside from Steven, his life bore the pain and loss of nearly everyone he loved. Married at the age of thirty-six, his wife, Maria Augusta Mahan, died only two and one-half years later. The only child of the marriage, a daughter named Ella Marie, contracted scarlet fever and died before reaching her fourth birthday.

Although Joseph was a career educator, after the death of his wife and in middle age, he redirected his energy and became a businessman. He worked for a New York City firm, Alsop and Company, for approximately three years and displaying remarkable aptitude but earned only $125 per month as a sales supervisor. When the opportunity arose in 1864 to double his earnings as a bookkeeper in San Francisco, he took it. Now forty-four years-old and engaged to Bertha Jemima Walker, a twenty year-old whose family shared common roots in St. George's Episcopal Church, Joseph was ready for a new start. He and his young bride moved to San Francisco soon after the wedding and together they discovered an entirely new world.

Everything seemed different, in an odd sort of way, but Joseph and his bride adjusted and prospered in the process. He referred to himself as a commission merchant in minerals and chemicals, speculating in such products as borax and opium. In 1886, opium was not considered an illegal substance and was frequently prescribed for medicinal purposes. As the use of opium in America continued to escalate, thousands of dollars began to pour through Joseph's bank account. After only two and one-half years he was able to write back east and proclaim, "Last year was the most prosperous of my life." But if there was any degree of boasting to this comment, it centered around his excitement to be able to give most of his profits away to charity.

Another item of good news reported back east was the announcement of a new child that was due before the summer was over. Born on perhaps a day indicative of his life, Stephen Tyng Mather was introduced to the world on July 4, 1867. Unable to name him, he was simply referred to as "the boy" for nearly the first year of his life. It was not until impatient relatives proposed naming him after the rector of St. George's, Stephen Tyng, did a name finally stick. Two years later another boy was born into the family, Joseph Wakeman Mather, Jr. or "Jossie" as he came to be known.

At the age of six, Stephen's mother began to experience issues with her health. Although she was still quite young, she was forced to leave her family and enter a sanatorium, first in California, then east where she permanently lived. Joseph senior remained in San Francisco to attend to his business and care for the boys. His business success allowed the boys to attend private school but while in college, Stephen earned his way by selling books during the summer. Stephen faithfully communicated with his mother until after he graduated from the University of California at Berkeley, class of 1887. Without a job and like many twenty year-old graduates, Stephen didn't have a firm idea as to a career path. He told his mother he may seek a living by entering a mercantile house, but for the time being, he wanted to spend time with her in New York.

Stephen's father, Joseph, and younger brother, Jossie, remained in San Francisco until the following year. Young nineteen year-old Jossie had finished high school and was working for an insurance company when he was diagnosed with spinal meningitis. Within a week, he died. Needless to say, his father was devastated. Nothing now remained for Joseph in California. He settled his affairs and at the age of sixty-eight, moved east as quickly as he was able. As government regulations began to restrict the opium trade, Joseph directed a lot of his investment capital, which he liked to refer to as speculative "adventures," into the borax industry. He was greatly invested into Pacific Coast Borax and used his connections with it's owner, Francis M. Smith, to open an office representing the company in New York City.

Arriving in New York a year earlier than his father, Stephen Mather began work as a reporter for the New York Sun and remained there for approximately six years. This experience not only provided him foundational relationships in his career, it also helped form and refine the natural abilities that served him so well for the rest of his life. Mather's experience with the Sun molded him into someone with a keen awareness of the American mindset. He possessed a gift in creating a story of interest and, if alive today, he may have been referred to as a marketing genius. This was Mather's gift: He was able to transform his visions into ideas that motivated others to action.

By 1893 Joseph W. Mather, Stephen's father, had been working as the administrator for Pacific Coast Borax's operation in New York City for approximately five years. Pacific Coast Borax, owned by Francis Marion Smith, aka the "Borax King" or "Borax Smith," was the world's largest borax mining operation of the day. At the same time, Stephen began courting a woman by the name of Jane Thacker Floy but her family held a less than favorable view of Stephen's occupation as a reporter for the Sun. Although content working as a reporter, he became more welcoming to a change in his career path. With his father's influence, Stephen accepted a position as the advertising manager for Pacific Coast Borax and later that same year married Miss Floy.

Now, all of 26, the younger Mather's marketing genius paid immediate benefits to Pacific Coast Borax. Mather approached company owner, Francis M. Smith, with the idea of advertising borax by using the term, "20-Mule Team Borax" as the company slogan, while continuing to display a picture of such on their product. Smith initially refused because he thought it more important to have his name on the box. Eventually Mather's persistence paid off and Smith finally consented to the change. Although long-line mule teams had been around decades by this time, and in some places actually consisted of two draft horses and eighteen mules, the general public hadn't much exposure to this fact. Instinctively knowing that "Two horses and eighteen mule" Borax was not the easiest expression for the tongue, Mather created the slogan that would be used for the next 100 years, "20-Mule Team Borax." Borax sales quadrupled and the following year Mather was invited to work as the advertising manager for Pacific Coast Borax at their main office in Chicago.

Mather understood the dynamic that the American public desired a dependable product that was strong and powerful, like a 20-Mule Team, that would work for them. Given the choice of another brand and the one portraying the strength and tenacity of twenty mule teams hauling ore out of the inferno of Death Valley, who could resist? Mather's employer, Francis Smith, however, didn't understand the value of advertising and left young Mather with a huge task and very little funding. It was Mather who was largely responsible for educating the American public as to the benefits and uses of borax. He created an image in the American mindset that every home needed to have a box of 20-Mule Team Borax in their home. Without much of a budget, he enlisted the talent of fellow New York Sun reporter, J.R. Spears, who was later to write a book, Illustrated Sketches of Death Valley And Other Borax Deserts of the Pacific Coast. The purpose was to expose the public to, and generate interest in Death Valley and borax.

In 1894 Mather was working in Chicago and was introduced to the man who would ultimately become his future partner. This was the other member of the odd couple, Thomas Thorkildsen. Thorkildsen was the son of a Norwegian immigrant lumberjack, born in Wisconsin and two years younger than Mather. He worked his way up through the ranks of Pacific Coast Borax and by the time he met Mather, he had been at the company for five years, holding the position of sales manager. Unlike Mather, Thorkildsen lacked the formal education and polish Mather possessed. This is not to say Thorkildsen lacked intelligence, quite the opposite. Thorkildsen was a brilliant salesman and an excellent strategist. He seemed to lack refinement and social boundaries, a point to be addressed later. If the two individuals held a common characteristic at all, it would be that both were visionaries and risk takers.

Thomas Thorkildsen | Click image to enlarge

|

Mather's arrival in Chicago demanded Thorkildsen take a less prominent role with Pacific Coast Borax. Although he retained his title as sales manager, a position he had held for a year, Mather was established as the advertising manager and was clearly Thorkildsen's new boss. In his private letters to Mather in subsequent years, Thorkildsen confessed that he tried to find fault with Mather but found him to be, "one of the brightest and truest men I had ever met." Rather than attempt to discredit Mather, Thorkildsen attempted to convince Smith that the two should hold the position as co-managers. When this failed, Thorkildsen became friends with Mather and smoldered with disdain for his employer, Francis M. Smith. Apparently the view of Smith was one many shared.

During the four years Thorkildsen and Mather worked together at Pacific Coast Borax, they became very close friends. It was obvious, however, that Thorkildsen wasn't happy with Smith and routinely plotted against him. Mather, who had his own issues with Smith, was his confidant in these schemes. By this time Stephen Mather had ample exposure to Smith's questionable business practices and was also keenly aware of his father's disgust with him. The elder Mather, Joseph, quit working for Smith about the same time Stephen left to work for Smith in Chicago. Smith had made promises to the senior Mather that he failed to keep and it placed Stephen Mather in a place of split loyalty between his father and employer. Mather was also made aware of how Smith treated other employees. In one instance, a woman of noble character and talent was paid a monthly salary of approximately $65. She was dismissed in order to cut cost and when she couldn't find work elsewhere, Smith rehired her weeks later at $40 per month.

Thorkildsen was determined not be be cast aside like this, make the best of his situation, and make Smith pay in the process. In one plot he secretly wrote to Mather explaining that he and Stephen could skim profits from ore transportation costs by signing a long-term rail contract for less costs, then charging Smith the regular price. Thorkildsen boasted to Mather that they could make $10,000 each on an annual basis and according to Thorkildsen in August 1897, "This is my best scheme I know of up to date." At a time when a good annual salary was $1,500, this was a fortune. There is no indication as to whether or not Mather ever acted on any of Thorkildsen's "fancy dreams" as he put it, but it did not discourage Thorkildsen from enlisting Mather's support. Near the same time Thorkildsen wrote to Mather stating, "Why should you handicap yourself when you are being treated so shamefully by Mr. Smith? Mr. Smith does not care how he treats you or how he fulfils his promises to you. It is all self with him. It is now time to turn the tables."

All the elements of a storm were brewing over Pacific Coast Borax and the following year, in 1898, Thorkildsen was caught backdating order forms after price increases were implemented. He did this as a favor to friends and preferred customers. Smith was infuriated with him and demanded his resignation but as Thorkildsen stormed out, he announced he was going to start up his own borax company. Smith's response was to return the threat by stating that if Thorkildsen did such a thing, Smith would, in essence, bury him. Both threats would prove to be true, but not quite as one might expect.

Later that same year, Thorkildsen took his life savings of $17,000, left Chicago and heading west to Southern California, he purchased a borax mine on Frazier Mountain in Ventura County. It's apparent that this move wasn't based on mere impulse, but had been on his mind for a period of time. Thus, Thorkildsen's termination of employment from Pacific Coast Borax simply sped up the process.

Although Mather stayed on with Pacific Coast Borax in Chicago, he became president of the newly formed Thorkildsen-Mather Borax Company in 1898. Stephen Mather and his father, Joseph, secretly financed the new mining operation while Stephen used his industry contacts with Pacific Coast Borax to advance the interests of the Frazier Mountain mining operation.

A couple of years later, in 1900, Smith wrote to Stephen Mather, perplexed as to how to track Thorkildsen's shipments of product from the Ventura mines. Smith states to Mather, "…possibly a large portion of the Boracic Acid which goes through Thorkildsen's hands goes directly to the pork packers. Our trade in that direction, as you know, has fallen off materially. It is evident that Thorkildsen‘s trade in the East is very limited; therefore, his trade must be West, in your territory, and naturally from buyers who formerly bought of us, certainly, very largely from these people." Although Smith was correct in his assumptions, he had no idea that the culprit was the recipient of his letter, Stephen Mather. Smith then asks of Mather, "I wish you would put your wits to work in this direction and see if you cannot give us some information, either definite or otherwise, on these lines." Smith, blindly, had put the fox in charge of investigating the hen house. In the end, Mather's secret alliance with Thorkildsen was successful and the Frazier Mountain mining operation became lucrative.

Three years later, in 1903, Mather had a nervous breakdown in Chicago. He was a high-strung individual, described as being full of energy and a workaholic. He was also caring, extremely personable, persuasive, made friends easily and maintained loyal friendships. The other side of his personality is that he was prone to periods of isolation, depression and moodiness that haunted him for life. His relief for these periods of his life was to escape into nature, thus laying the foundation of his passion and eventually establishing the National Park Service. During Mather's breakdown, Smith refused to pay his wages. This resulted in Mather finally breaking away from Francis Smith and Pacific Coast Borax. In 1904 he left Chicago to join Thorkildsen at the Frazier Mountain mine.

Thorkildsen's personality was quite the opposite of Mather. Thorkildsen was careless with money, drank too much, had horrible relationships with women and was quite egocentric. Stories abound regarding the lifestyle of Thorkildsen and the wild parties he hosted at his home in the Hollywood Hills. It was not uncommon for him to invite guests to dinner and after enjoying a meal and drinks, for him to take off all of his clothes and parade around in the buff. He was very prideful of his physique and loved to display it when the opportunity arose. At a later point in life he caught a man in bed with his wife and chased the naked man down the hill from his home. The naked man circled back to retrieve his clothes but slipped near the pool, fell in, and drowned. At another party, an intoxicated Hollywood starlet also fell into the pool and drowned but was not noticed until the following day. Mather and Thorkildsen could not have been more different.

When Mather joined Thorkildsen at Frazier Mountain in 1904, Thorkildsen had been running the day-to-day operations of the successful venture for six years. Mather was just at the end of recovering from the nervous breakdown he had in Chicago. It is unlikely that Mather, who had never actually worked in a mine, had any desire to spend time underground with pick and shovel in hand. Mather's personal therapy was to be outdoors in nature, that's what settled his spirit and calmed his mind. At the same time, the last thing Thorkildsen needed, was Mather looking over his shoulder and trying to help run the mine. It wasn't long thereafter that Mather and his wife set out for an extended trip to Europe. There, he rekindled his passion and interest in nature and returned home with an acute awareness of America's need to improve public access to the natural beauty the country offered.

In Spring, 1905 two gold prospectors, Louis Ebbenger and Henry Shepard, happened upon a rich deposit of borax in Tick Canyon. They lacked the resources to mine and process the mineral themselves and subsequently sold their claim to Thorkildsen for $80,000. Since the Frazier Mountain site was nearly mined out by this time, it couldn't have happened at a better time. The Thorkildsen-Mather Borax Company was still in business but it was now being marketed under a different name; the Sterling Borax Company.

Evidence of Mather's marketing savvy was displayed on the outside of every box of borax the company sold. Rather than promote a product with a difficult name that few could remember or pronounce, i.e., Thorkildsen-Mather Borax, the label depicted the currency symbol for the British Pound and simply read in bold print, "Sterling Borax." It's interesting to note that the best man at Mather's wedding was a prominent writer who worked with him at the New York Sun newspaper. His name was Robert Sterling Yard. The regal sound of the name "Sterling" promoted a sense of value and power. It's likely this name was filed away in Mather's creative mind until he had a use for it.

Within three years the mine was operational and began producing approximately eighteen to twenty thousand tons of marketable borax a year. This translated to an annual gross profit of approximately $500,000, which in 1908, was a huge fortune.

The mining operation itself was in a community named Lang, which was comprised of not much more than couple dozen structures. It was a very small community that has all but disappeared after the mine closed in 1921. What little remains of the mining operation is fenced off by current property owner, Rio Tinto Minerals, a successor company that evolved from Pacific Coast Borax and U.S. Borax. Access to the property is possible by special permit, usually through a rock hound or hiking club that is given permission to traverse the area a few times a year. The site of the mine is located in modern-day Sanata Clarita Valley, just off of California State Highway 14 via the Aqua Dulce Canyon Road exit to Davenport Road. On the north side of the road is the U.S. Borax "No Tresspassing" sign, and to the south is a continuation of the old Sterling Borax mine wash. Samples of Colemanite, tossed aside as worthless during this time, can be seen near the side of the road.

In all likelihood, Thorkildsen was a resident of Lang and ran the operation from there. All appearances are that the partnership agreement between Thorkildsen and Mather were such that Thorkildsen ran the day-to-day operations of the mine while Mather was not only a joint financial investor, but supported the operation by running the marketing and distribution of the product. In subsequent years, Mather is reported in third party accounts as coming to Lang and meeting with Thorkildsen but the two are never cited as working the actual mine site together.

In 1911, only three years after the Sterling mine became operational, an offer to purchase the Sterling Borax Company was made by none other than Francis "Borax" Smith, owner of Pacific Coast Borax and former employer of both Thorkildsen and Mather. Thorkildsen quickly accepted Smith's price of $1.8 million as well as a concession to keep Thorkildsen and Mather on the payroll for an additional ten years. Taking into account that the Sterling mine produced a gross profit of $1.5 million during its first three years of operation Thorkildsen and Mather walked away with nearly $3 million and a job for the next decade. In today's economy, some financial experts state that $3 million in 1911 had the purchasing price of approximately $500 million today. In the end, both Thorkildsen and Smith's threats came true. Thorkildsen did in fact, go out and start his own borax company and Smith, did in fact bury Thorkildsen…but he buried him in a pile of cash. Both Thorkildsen and Mather had become very wealthy from their borax mining venture.

Although Pacific Coast Borax owned Sterling Borax, it continued to operate as a separate division under Smith's conglomerate and Thorkildsen remained as president of the operation while Mather served as vice president. Only a few years later, Francis Marion Smith became financially overextended and went bankrupt. Pacific Coast Borax and Smith's holdings were eventually acquired by U.S. Borax and today, U.S. Borax owns the property in Tick Canyon where the Sterling Borax mine operated over a century ago.

Having made their fortunes, the odd couple continued to be friends and partners but

their lifestyles swung at opposite ends of the pendulum. Even prior to selling out to Smith, Thorkildsen purchased six acres of land and built a hilltop mansion on Alpine Drive in up and coming Beverly Hills. He was known for lavish parties and speedy women. His home became a watering hole for many in the Hollywood industry and Thorkildsen's personal life and antics were a constant source of controversy. He was once chided by a judge who stated that the details of Thorkildsen's case were so vulgar, he had difficulty even mentioning them in court.

Thorkildsen's spending habits became increasingly more reckless and his debts continued to build. This did not deter him from taking extravagant hunting trips and buying a yacht to entertain a handful of beautiful women on a world cruise. Only twelve years after selling Out to Pacific Coast Borax, Thorkildsen's fortune had dwindled to nearly nothing. The borax of the Sterling mine had become exhausted, Lang became a ghost town and he was left with only his existing home and a small pension. By the time of the Great Depression, he lost

that as well. Thorkildsen died broke and alone in a La Crescenta, California nursing home in 1950.

Stephen Mather, on the other hand, took his fortune in hand and set out to change the way America valued and viewed its natural parklands. He stated that America possessed spectacular scenery that rivaled anything in Europe. Unfortunately his experience was to note that the parklands were in a horrible state of repair and access to them was extremely difficult. As a member of the Sierra Club, Mather gained exposure to the thoughts and environmental views held by John Muir. Although it is uncertain as to whether Mather met with Muir while on a hike in the Sierra Mountains in 1912 or met him at a later time, he was certainly very motivated by him. His exposure to Muir's passion for nature challenged Mather to take up the banner of preserving, protecting and expanding the national park system. Mather never looked back. From 1912 to 1914 he was in Washington D.C. on several occasions as an advocate of the national parks.

In 1914 Mather wrote a letter the Secretary of the Interior, Franklin K. Lane, describing the horrible conditions of the national parks. Although Lane attended the University of California Berkeley, he never graduated and he did not know Mather at that time. Regardless, Lane was moved by Mather's letter and obvious passion for nature so he replied by stating, "Dear Steve, If you don't like the way the national parks are being run, come on down to Washington and run them yourself." With the challenge made, Mather responded and after crossing a few hurdles, Mather was sworn in as assistant to the Secretary of the Interior on January 2, 1915.

Unlike the great majority of government bureaucrats, Mather had no interest in career advancement, salary or self-promotion. He was independently wealthy and was willing to pull out his checkbook to advance the cause. He supplemented the salary of his assistant, Horace Albright, while paying the entire salary for his former best man, Robert Sterling Yard. Together they publicized the plight of the national parks, cut red tape and got the job done. When there were no funds allowed for projects, Mather either raised the money on his own or in many instances, paid out of his pocket. Mather had to fight off those who attempted to use the national parks for their own gain, some of whom even demanded the slaughter of nearly extinct species. He fought off ranchers, miners and lumber companies in order to preserve the beauty of our national parks. During World War I Mather had to fight to protect the buffalo herds from being killed as cleaver opponents used the ploy that buffalo meat was needed to feed the hungry troops.

A statement, likely penned by his assistant, Horace Albright, in Mather's 1920 Annual Report to the Secretary of the Interior, Mather is credited as stating:

"Who will gainsay that the parks contain the highest potentialities of national pride, national contentment, and national health? A visit inspires love of country; begets contentment; engenders pride of possession; contains the antidote for national restlessness. It teaches love of nature, of the trees and flowers, the rippling brooks, the crystal lakes, the snow-clad mountain peaks, the wild life encountered everywhere amid native surroundings. He is a better citizen with a keener appreciation of the privilege of living here who has toured the national parks."

Stephen Mather resigned from the National Park Service due to his poor health in 1929. Approximately a year later, he died after suffering from a stoke. Appreciation for his life's work is expressed in the statement displayed in many national parks today:

"He laid the foundation of the National Park Service, defining and establishing the policies under which its areas shall be developed and conserved unimpaired for future generations. There will never come an end to the good that he has done."

The conclusion and significance of this story is quite simple, really. First, its to point out the significance of a small mining operation in Santa Clarita Valley's backyard referred to as Tick Canyon and a mineral discovered there named borax. Without it's discovery and the wealth it generated, we may have never heard of Stephen T. Mather or experienced the National Park Service as we know it today.

Secondly, there's a moral to the story of the "odd couple." Wealth and resources are simply tools we are entrusted with while here on earth. If we use them for our own selfish pursuits of personal satisfaction, it is easy to become blinded and distracted from the greater good of serving others. Thorkildsen was a man with money and no vision for others. He died broke and alone. Mather was a man of great vision and selfless in his pursuit to benefit and serve generations to come. His name is memorialized on National Park Service plaques across the country and schools are named after him. And when we see the awe and wonder on a child's face while, for the first time, gazing upon a Giant Redwood Tree, we can give some credit to Stephen Tyng Mather for that too.

Edward Keebler is a historian who currently resides in Stevenson Ranch.