|

|

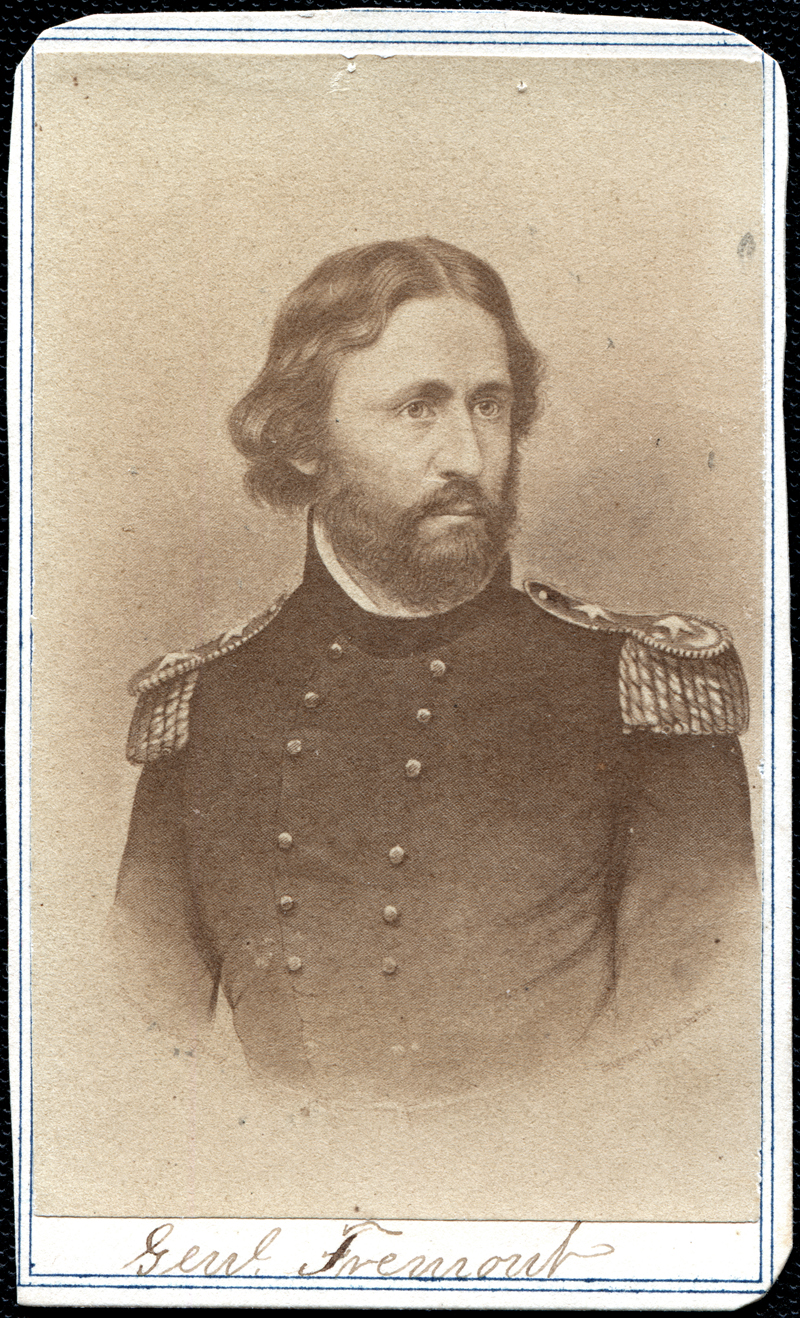

"The Pathfinder"

Click image to enlarge Gen. John Charles Frémont, carte de visite (2.25x3.75"), 1850s or 1860s.

The name John Charles Frémont (Fremont) is synonymous with President James K. Polk's policy of "Manifest Destiny" — the westward expansion of the United States in the 1840s. Born Jan. 21, 1813 in Savannah, Ga., Fremont studied excelled in math at Charleston (S.C.) College but was expelled in 1831 for bad attendance. He joined the U.S. Navy and taught math on a warship before joining the U.S. Topographical Corps (later renamed the Army Corps of Engineers) as an explorer in about 1838. A skilled surveyor who could draw accurate maps useful for push west, Frémont was heading his own expeditions by 1841, surveying the Missouri River, the Oregon Trail and the Sierra Nevada. In that same year (1841) Frémont married Jessie Benton, the 17-year-old daughter of Sen. Thomas Hart Benton, the architect of the Manifest Destiny movement. Frémont, whom the press would dub "The Pathfinder" (even though Kit Carson did most of the "path finding" for him), led three major expeditions to the Far West — in 1842, 1843-44 and 1845-47. War broke out between the U.S. and Mexico in 1846 and Frémont, with knowledge of the territory, was sent to California. Frémont led much of the Bear Flag Revolt at Sutter's Fort in the Sacramento Valley while Mexican Gen. Andrés Pico was fighting — and defeating — U.S. Gen. Stephen Kearny at the Battle of San Pasqual near San Diego. On Jan. 9, 1847, Frémont and his 100-man "buckskin battalion" arrived at Castaic Junction from the north, on their way to meeting Pico, and probably stopped overnight at the Del Valle ranch home. The following night, the troops camped at the Newhall Pass, somewhere in the vicinity of today's Eternal Valley Cemetery (according to Perkins, at the intersection of Highway 6 and San Fernando Road, now known as Sierra Highway and Newhall Avenue). The next morning Frémont and his company departed on foot, crossing the San Gabriels through Frémont Pass (later confused with Beale's Cut, which was about a quarter-mile to the west) as they marched on to face Pico in the San Fernando Valley. It was a bloodless victory. Pico handed over his sword to Frémont in what is known as the Capitulation of Cahuenga. General peace came a year later, on Feb. 2, 1848. Following the war, which added California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas to the Union, Frémont led another expedition in 1848-49, was court-martialed for mutiny and retired to his ranch in Mariposa, Calif., where he found gold and got rich. Voted into the U.S. Senate in California's first election following statehood in 1850, Frémont served a two-year term and became the Republican Party's first presidential candidate in 1856, running on an anti-slavery platform. Frémont was appointed Major General in the (regular) U.S. Army in 1861 and commanded the Western Department of the Union Army during the Civil War, but President Abraham Lincoln relieved him of his duties after Frémont issued an emancipation proclamation freeing slaves in Missouri — prior to Lincoln's own Emancipation Proclamation. Frémont lost the fortune he had made in California gold when he dabbled in railroad investments after the Civil War. He got a job as Territorial Governor of Arizona, a post he held from 1878-83. In 1887 he returned to his Mariposa ranch and lived just long enough to see the U.S. Army restore his rank of Major General. He died July 13, 1890 in New York City.

LW2225: 9600 dpi jpeg from original carte de visite |

See Also: • Mexican-American War 1846-1848 • Kit Carson • About Fremont Pass (Perkins) • The Pathfinder (Reynolds)

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.