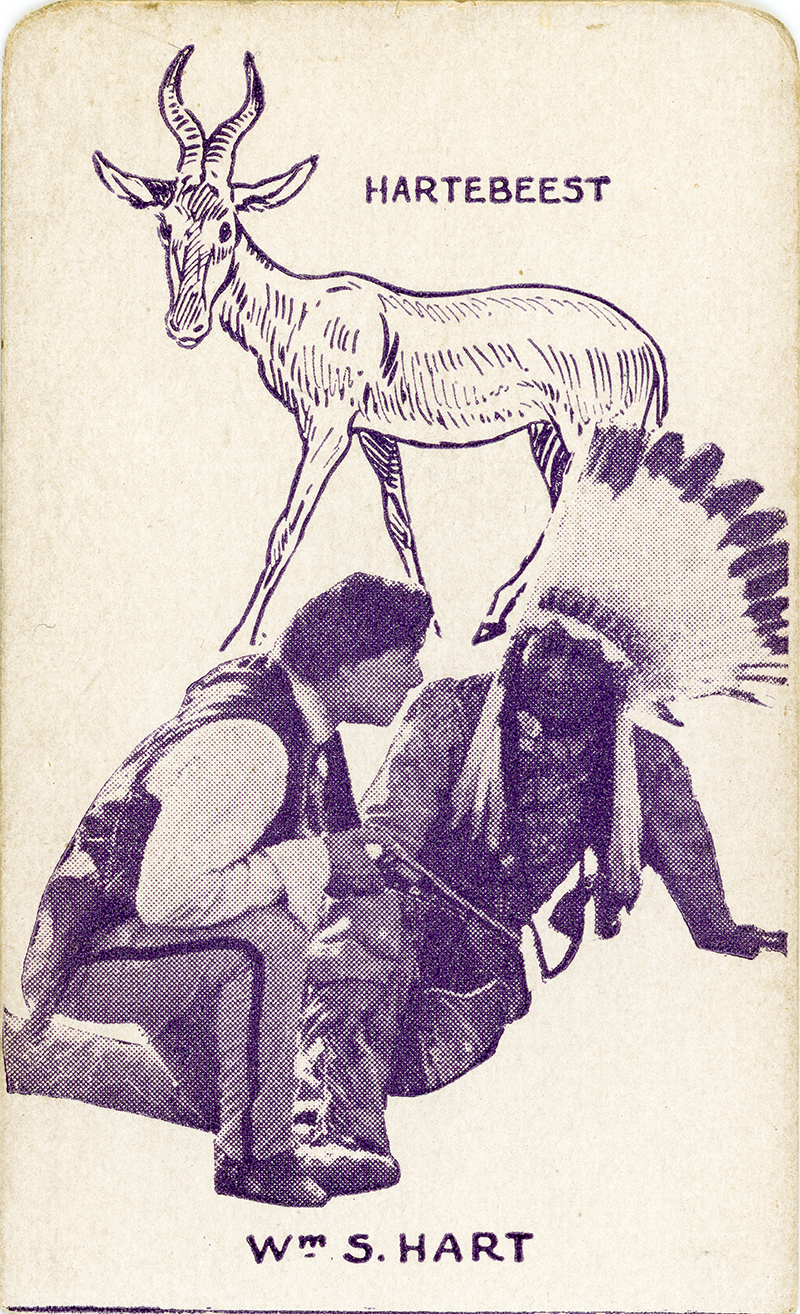

Scene from "White Oak"

William S. Hart and Chief Luther Standing Bear

Click image to enlarge

| Download archival scan

In a scene from "White Oak" (1921) that was also used on this tobacco card, William S. Hart (as Oak Miller) and Brulé Lakota Chief Luther Standing Bear (as Chief Long Knife) are paired with a hartebeest on this little 1¾x2¾-inch "Movie Stars and Animals" strip card from the 1920s. Issued in the United States and intended to be collected by children, the cards came in strips that had to be separated. The backs were blank (buff-colored card stock); the fronts had a printed background of white, green, blue, red, pink, orange or yellow. This one has a white background. As for the pairing with a hartebeest (an African antelope, aka kongoni), it's an obvious play on Hart's name. We don't know exactly when in the 1920s they were issued, but since Newhall child actor Buzz Barton (William Lamoreaux) appeared on this particular card, we can tell they were being issued around 1927-1928.

About "White Oak." Produced by the William S. Hart Company; distributed by Paramount-Artcraft; released December 18, 1921; ©August 15, 1921; seven reels (6208 feet). Directed by Lambert Hillyer; screenplay by Bennet Musson from the story "Single Handed" by William S. Hart; photographed by Joe August; art director, J. C. Hoffner; edited by William O'Shea; art titles by Harry Barndollar. CAST: William S. Hart (Oak Miller); Vola Vale (Barbara); Alexander Gaden (Mark Granger); Robert Walker (Harry); Bertholde Sprotte (Eliphalet Moss); Helen Holly (Rose Miller); Standing Bear (Chief Long Knife). SYNOPSIS: Oak Miller, square gambler, deals cards at the Red Fort Saloon, Independence, Missouri, and watches for a chance to punish the man who deceived his sister Rose with a promise of marriage. Rose is ill and under the care of Barbara, with whom Oak is in love. Eliphalet Moss, stepfather of Barbara, is jealous of Oak. Granger, the man Oak is searching for, comes to town disguised and determines to possess Barbara. Granger plots with Chief Long Knife to attack a rich emigrant train. The chief is unaware that Granger misused his daughter, Little Fawn. Rose dies. Barbara's stepfather tries to enter the cabin at night and is shot to death by her brother Harry, a tool of Granger's. Barbara is suspected of the crime. To save her, Oak robs Moss's bank and leaves evidence pointing to himself as the robber. Oak is arrested for murder. The emigrant train is attacked [by Indians]. Barbara sends a dog with a message for Oak. He breaks jail, goes to the rescue of the emigrants and the Indians are repulsed [when he captures Chief Long Knife as a hostage]. Long Knife kills Granger. Barbara and Oak are united. [Exhibitor's Trade Review, November 12, 1921] REVIEWS: Once again Bill Hart has undertaken to write his own story and if he can continue the good work there's no reason why he shouldn't, for White Oak is a splendid picture. ... It contains plenty of action, fine detail and a real atmosphere of the old West with Injuns 'n' everything. And best of all it offers probably the most popular of Western portrayers in a role ideally suited to him. As usual, Hart does fine work. ...[Wid's, November 6, 1921] The star's fans will find White Oak immensely interesting, for it presents him in his best-liked role of a hard-riding, straight-shooting man. The continuity is smooth and the suspense well built up. Some of the exterior scenes, too, are especially striking, notably those where the Indians circle in clouds of dust around the beleaguered caravan. But it does tax the imagination a bit to see the hero's revolver bringing down galloping Indians a quarter of a mile away. Perhaps our own lack of skill with the weapon makes us unduly skeptical, but we should like to see such shooting in real life. [Sumner Smith, Moving Picture World, November 12, 1921]

About Chief Luther Standing Bear. Luther Standing Bear knew the West when it was still tame. Born in the 1860s in South Dakota, he was named "Plenty Kill" (Ota Kte) by his father, a Brulé Lakota chief with plenty of kills under his belt (or, notched on his coup stick). He was raised in a traditional way that was soon shattered. His experiences would fill a book (and they do; we can't give it justice here). He was the first boy to enter the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania where he took the name Luther, and where he tried, and succeeded, in doing well in order to make his father proud. Like his father (and like author Helen Hunt Jackson*), he supported the 1887 Allotment Act (aka Dawes Act) because he saw land ownership as a pathway to U.S. citizenship, which was denied most Indians until 1924. (With a century's hindsight, the Allotment Act is seen as having been detrimental to Indian land ownership.) He spent a season with Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show and performed for the king of England; given Luther's formal education and his natural, inherited leadership abilities, Col. Cody put him in charge of the other Indian performers. In 1905 he was named chief of the Oglala Lakota — a position he held only briefly. Reservation life and second-class citizenship were not for him. Eventually he came to California where he met film producer Thomas Ince, who hired him as a consultant (but, from Luther's autobiography, Ince must not have listened too well). His first screen credit was for the 1916 film adaptation of H.H. Jackson's "Ramona" (a lost film). He appeared in the 1921 Hart vehicle, "White Oak," and the two men evidently maintained a friendly relationship as seen here. Here's the "but." Luther doesn't devote many pages of his autobiography to "Hollywood" except to say that Ince once told him: "Standing Bear, some day you and I are going to make some real Indian pictures." The day never came. "I wrote Mr. Ince that I was willing to work for my people and to help him, if he would accept my ideas and my stories. I waited for a reply, but none came." "I have seen probably all of the pictures which are supposed to depict Indian life," Luther writes in 1928, "and not one of them is correctly made." Not one.

* Jackson died before the act was adopted. She was an early proponent who believed the government's "refusal of the protection of the law to the Indian's rights of property ... must cease" ("A Century of Dishonor," 1881 [Dover 2003 edition pg. 342]).

LW3747: 9600 dpi jpeg from original strip card purchased 2020 by Leon Worden.

|