|

|

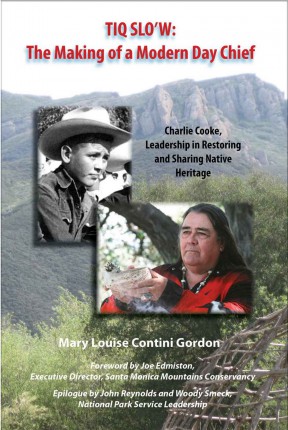

Charlie Cooke

Charlie Cooke

Spritual Leader, Fernandeño-Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

October 2, 1935 — September 21, 2013

By Leon Worden | SCVNews.com | Sunday, September 22, 2013

|

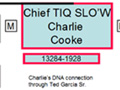

Charlie Cooke, the Santa Clarita Valley's most prominent Indian leader for more than four decades, died Saturday morning at his home in Acton after a long ailment. Cooke, a spiritual leader of the Fernandeño-Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, who also embraced the Chumash culture, was 77. "He taught me that it's important to reach down and touch mother earth and know where you came from, always remember who we are," said his cousin Ted Garcia, who assumed the mantle of hereditary chief of the Southern Band of Chumash Indians four or five years ago when Charlie's health started to slow him down. Since the early 1970s, Charlie was go-to person whenever a builder or public agency needed an Indian monitor for a housing development or a road project that threatened a prehistoric native American site in northern Los Angeles County or western Ventura County. Under his watchful eye, archaeological relics and burials were either preserved in place or relocated to venues where they could be handled and cherished with the proper respect. "When he handed his (chief's) staff to me at Playa Vista," Ted Garcia said, "there were many holes in it," each one representing a victory in the fight for the preservation of Indian traditions.

Ted remembers Charlie saying: "There are many battles that I've won, and I've lost more than I've won, but I'm proud of my accomplishments." Charlie conducted blessings and represented several Southland tribes — including neighboring groups such as the Chumash (Ventura-Santa Barbara) and the Kawaiisu (Tehachapi) — in political settings. Charlie's own lineage was Tataviam (Santa Clarita Valley), Kitanemuk (Antelope Valley) and Tongva (San Fernando Valley-L.A. basin, i.e., Fernandeño-Gabrielino), along with some French and German. Joe Edmiston, executive director of the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, met Charlie in 1979, the year the state Legislature created the conservancy to advocate for lands threatened by rapid urbanization. "Charlie Cooke ... has blessed the lands that have sustained these populations (of diverse flora and fauna) and shared its blessings with the people who have come to these remarkable mountains," Edmiston says in the foreword to a brand-new book about Charlie's life. "Charlie was a great source of tribal knowledge," said Rudy Ortega Jr., the Tomiar, or tribal captain, of the Fernandeño-Tataviam Band of Mission Indians. "I am honored to say he was my cousin and a great advocate of preservation of our tribal culture." "He was keen on preserving and protecting tribal cultural resources and historical sites of both Tataviam and Chumash lands," Ortega said Sunday. "In 1984, when I was 12 years old, I got the privilege to see Charlie and my father, Rudy Ortega Sr., work together on mitigating a disturbed cultural site at Encino."

Ortega Jr. said Charlie "worked closely with the National Parks Service, lending his knowledge to further preserve Satwiwa Native American Indian Cultural Center in the Santa Monica Mountains for generations to enjoy." Similarly, Charlie played a key role in the establishment of the Chumash Indian Museum in Thousand Oaks, Ted Garcia said. Charlie — Charles Robert Cooke — was born Oct. 2, 1935, in San Mateo to Cy and Katherine Cooke. Cy was a Newhall cowboy; Charlie grew up in the Santa Clarita Valley and attended the K-8 Newhall School in the 1940s and the new high school, Hart, in the early 1950s. By profession he drove a cement truck and worked on so many construction jobs that he "knew every deer trail in the San Fernando Valley, Santa Clarita Valley and Leona Valley," Ted Garcia said. "He never took the freeway. He was always taking back roads and pointing out interesting things to us." Charlie was scheduled to tell his life story in a televised interview at next weekend's Hart of the West Powwow at William S. Hart Park in Newhall. Fortunately, his story has been preserved by author Mary Louise Contini Gordon in a new book, "TIQ SLO'W: The Making of a Modern Day Chief." The book was released Thursday on Kindle and is due to be released Monday in print. Charlie had planned to participate in book signings. The book is billed as an "ethnographic biography" that tells the story of Charlie as "a cowboy, a ranch hand, a rodeo champ, a Korean War veteran, a regular husband and father, and a truck driver. ... It is the story of this very same man who worked tirelessly to preserve (his) ancestral lands for posterity, for Cooke's descendants and those of the very people who took lands from his forbears." Charlie's ancestry has been thoroughly researched by Dr. John Johnson, curator of anthropology at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, who has worked with local Indian tribes for many years in their struggle to compile the extensive documentation required for federal recognition. "The problem," Charlie Cooke said in a 2000 interview, "is that if you can't prove your native American ancestry through the mission records, you don't classify as an Indian in the government's eyes." Steps in that direction took a leap forward in 2005 when mitochondrial DNA from a prehistoric burial at Ritter Ranch, north of Acton and west of Palmdale, was linked to living native Americans. It was unprecedented. And yet, federal recognition awaits the descendants of the first peoples of the Santa Clarita, Antelope and San Fernando valleys. Charlie Cooke leaves behind his widow, Linda (Enright) Cooke. He had four children (two by a previous marriage) and a great many cousins. Funeral services are pending.

|

SEE ALSO

Garcia Adobe ~1885

Charlie Cooke's Family Tree

Video: Author Mary Gordon on Charlie Cooke

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.