|

|

A Comparison of Tataviam Ethnobotany at Vasquez Rocks and Placerita Canyon

By

Sarah Brewer Thompson

January 19, 2014

|

One of the smallest of these groups, and one that inhabited our local area, was known as the Tataviam. Archaeological evidence shows long-term residence in areas throughout the Santa Clarita Valley and Acton-Agua Dulce (including Vasquez Rocks and Placerita Canyon), as well as a rich system of trade with both coastal and desert cultures from hundreds of miles away. Although most of the traditional ways that were specific to the culture, including their language, were lost within two or three generations after their assimilation into the San Fernando Mission, some valuable information has survived through a few avenues. This includes stories told by descendants, archaeological evidence, and studies of the natural environment. One aspect of Tataviam culture that is still relatively well understood is what food they relied on for survival. Ethnobotany — the study of the use of plants by a specific culture — is a science that can teach us a lot about a population. Luckily, due to the preservation of natural areas such as Vasquez Rocks and Placerita Canyon, we can study what plants were utilized by these men and women long ago. In one of the prominent texts on California archaeology and anthropology, "The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 8: California," archaeologists Dr. Chester King and Thomas Blackburn discuss ethnobotanical practices of the Tataviam. They note that the "primary vegetable foods in order of importance were the buds of the Yucca whipplei ... acorns, sage seeds, juniper berries and berries of islay (Prunus ilicifolia)" (Heizer 1990:536). While this is true as a generalized statement, there were many differences in the foodways of the Tataviam who lived at Vasquez Rocks, and those who lived in Placerita Canyon. Yucca whipplei Archaeological and botanical evidence suggest that the most important plants to the Vasquez Rocks Tataviam group were the yucca, juniper, sage plants and various oak species. Unlike in Placerita Canyon, the yucca plant (Yucca whipplei, aka "Spanish Bayonet" or "Our Lord's Candle") is often regarded as the most important food source. As King writes, "yucca provided the most reliable and plentiful source of energy available to people living at Agua Dulce" (1974:5). He adds: "South of Agua Dulce, the yucca within an east-west band two miles wide perhaps represents the most dense and extensive concentration anywhere." This can still be attested to today, as Vasquez Rocks and surrounding areas in Agua Dulce feature highly dense groupings of large, healthy yucca plants. The yucca is an extremely versatile and valuable plant. The root and stalk were cooked slowly in stone-lined earth ovens, which produced food that could be stored for up to a year. The seeds, heart and blossoms also provided food, while the thorny stems were a highly useful material used for weaving clothing, baskets, shelters, and for use as straps and fasteners. The yucca was (and is) also present at Placerita Canyon, but in much smaller quantities. It is believed the yucca was a food that was regarded for more special occasions in Placerita due to its limited supply, with its cordage a very helpful resource, and the sweet-tasting flesh of its stalk. King reports that the main time for collecting yucca was usually in early spring. Oak acorns Another plant family that proved useful to both the Placerita and Vasquez Rocks groups were various species of oaks. The scrub oak (Quercus dumosa) was, however, the only oak species that grew commonly in the Vasquez area. Placerita Canyon, as visible today, is an area richer in multiple species of oaks, including coast live oaks (Q. agrifolia), scrub oaks (Q. dumosa), black oaks (Q. kelloggii) and canyon oaks (Q. chrysolepis). As the yucca was the main food staple in Vasquez Rocks, the various oak species were the main plant food source in Placerita Canyon. The coast live oak and canyon oaks provided a larger and more regular yield of acorns than the smaller scrub oaks. The preparation of acorns for consumption was a highly involved process that included picking or collecting the acorns, letting them dry, grinding them by hand in a stone metate or bowl, and leaching out the tannins by soaking the ground material in water. After these steps, the acorns finally became an edible meal, often referred to as acorn mush. Although not the most appetizing product, it has tremendous nutritional value, and its production involved a process that likely brought families together and became a time for social interaction. Others The juniper tree also proved an important food source for those at Vasquez Rocks, as well as in Placerita Canyon. Because it was more highly abundant in the Vasquez area than in Placerita, the juniper (Juniperus californica) may have been more of a staple food there. The seeds were probably most commonly dried, then ground into a juniper berry mush, which was useful in making small cakes. Another plant utilized in both Placerita Canyon and Vasquez Rocks was the holly-leaved cherry (Primus ilicifolia). This plant is still plentiful in both areas. It was used more often for the seed within the bright red fruit, than for the fruit itself. These seeds, like acorns, were ground and toasted before being consumed. Additionally, the salvia, or sage, family of plants was also utilized at both locations. According to King's report, seeds were collected and then parched, ground and formed into small cakes, which also required stone grinding tools. These seeds were mainly gathered in the summertime and could be stored. By no means do the plants discussed here represent all of the various plant items used as food by the Tataviam. Rather, they were the staple items that were depended upon for the highest nutritional value. The evidence of early people's time in these areas can still be observed in the ground stone tools in which they carefully prepared their food, generation after generation. Knowledge of the foodways of these ancestors allows one to better imagine how it was to live in their time and place, surviving solely on what nature intended to provide. Perhaps in looking at how those who lived here before us survived on what the land provided, we can gain a new respect and appreciation for the many things we too often take advantage of today. Sarah Brewer Thompson was born and raised in Agua Dulce, where she learned to love and appreciate nature and history. She is a master's student at California State University, Northridge, and a docent at Vasquez Rocks Natural Area Park. Her areas of interest are local history, archaeology and animal studies.

|

Bowers Cave Specimens (Mult.)

Bowers on Bowers Cave 1885

Stephen Bowers Bio

Bowers Cave: Perforated Stones (Henshaw 1887)

Bowers Cave: Van Valkenburgh 1952

• Bowers Cave Inventory (Elsasser & Heizer 1963)

Tony Newhall 1984

• Chiquita Landfill Expansion DEIR 2014: Bowers Cave Discussion

Vasquez Rock Art x8

Ethnobotany of Vasquez, Placerita (Brewer 2014)

Bowl x5

Basketry Fragment

Blum Ranch (Mult.)

Little Rock Creek

Grinding Stone, Chaguayanga

Fish Canyon Bedrock Mortars & Cupules x3

2 Steatite Bowls, Hydraulic Research 1968

Steatite Cup, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x5

Ceremonial Bar, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x4

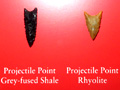

Projectile Points (4), 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig

Paradise Ranch Earth Oven

Twined Water Bottle x14

Twined Basketry Fragment

Grinding Stones, Camulos

Arrow Straightener

Pestle

Basketry x2

Coiled Basket 1875

Riverpark, aka River Village (Mult.)

Riverpark Artifact Conveyance

Tesoro (San Francisquito) Bedrock Mortar

Mojave Desert: Burham Canyon Pictographs

Leona Valley Site (Disturbed 2001)

2 Baskets

So. Cal. Basket

Biface, Haskell Canyon

2 Mortars, 2 Pestles, Bouquet Canyon

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.