Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

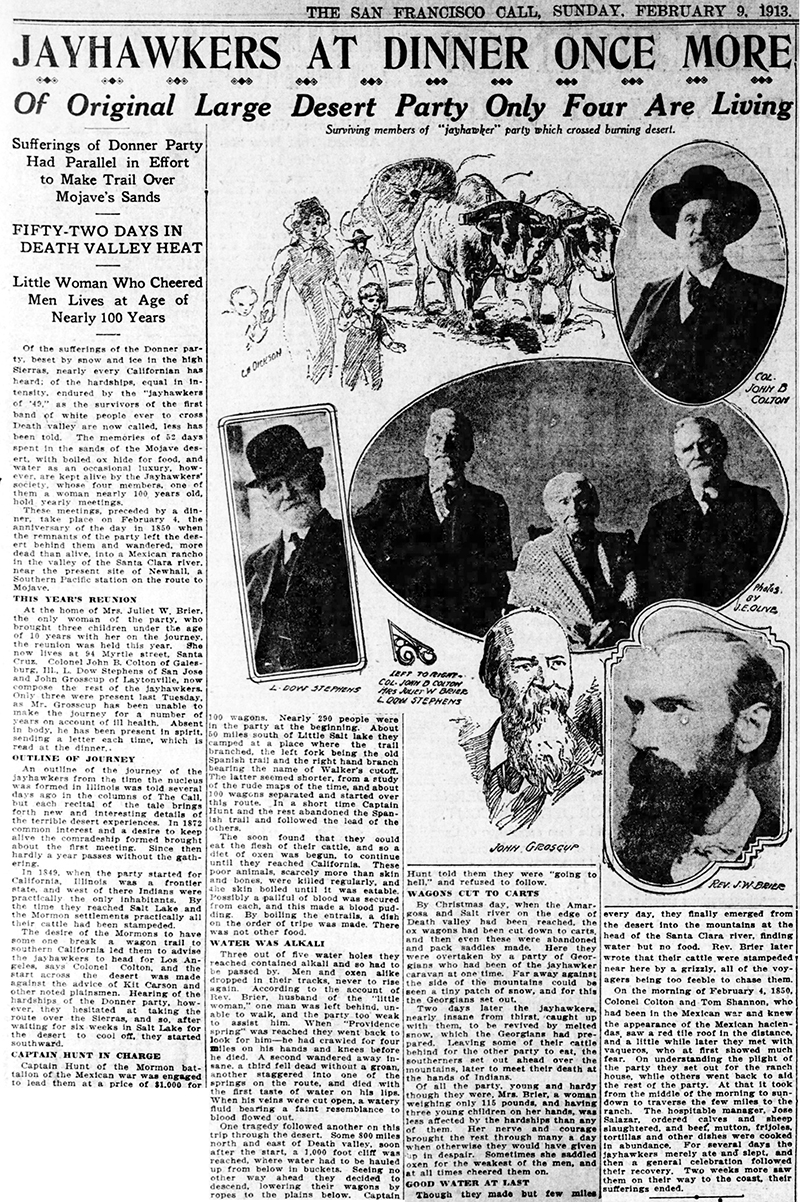

Jayhawkers At Dinner Once More

Of Original Large Desert Party, Only Four Are living.

Sufferings of Donner Party had parallel in effort to make trail over Mojave's sands.

Fifty-two Days in Death Valley Heat.

Little woman who cheered men lives at age of nearly 100 years.

The San Francisco Call | Sunday, February 9, 1913.

Of the sufferings of the Donner party, beset by snow and ice in the high Sierras, nearly every Californian has heard; of the hardships, equal in intensity, endured by the "Jayhawkers of '49" as the survivors of the first band of white people ever to cross Death valley are now called, less has been told.

The memories of 52 days spent in the sands of the Mojave desert, with boiled ox hide for food, and water as an occasional luxury, however, are kept alive by the Jayhawkers' society, whose four members, one of them a woman nearly 100 years old, hold yearly meetings.

These meetings, preceded by a dinner, take place on February 4, the anniversary of the day in 1850 when the remnants of the party left the desert behind them and wandered, more dead than alive, into a Mexican rancho in the valley of the Santa Clara river, near the present site of Newhall, a Southern Pacific station on the route to Mojave.

At the home of Mrs. Juliet W. Brier, the only woman of the party, who brought three children under the age of 10 years with her on the journey, the reunion was held this year. She now lives at 94 Myrtle street, Santa Cruz.

Colonel John B. Colton of Galesburg, Ill., L. Dow Stephens of San Jose and John Grosscup [sic: Groscup] of Laytonville, now compose the rest of the Jayhawkers. Only three were present last Tuesday, as Mr. Grosscup has been unable to make the journey for a number of years on account of ill health. Absent in body, he has been present in spirit, sending a letter each time, which is read at the dinner.

An outline of the journey of the Jayhawkers from the time the nucleus was formed in Illinois was told several days ago in the columns of The Call, but each recital of the tale brings forth new and interesting details of the terrible desert experiences. In 1872 common interest and a desire to keep alive the comradeship formed brought about the first meeting. Since then hardly a year passes without the gathering.

In 1849, when the party started for California, Illinois was a frontier state, and west of there Indians were practically the only inhabitants. By the time they reached Salt Lake and the Mormon settlements, practically all their cattle had been stampeded.

The desire of the Mormons to have some one break a wagon trail to southern California led them to advise the Jayhawkers to head for Los Angeles, says Colonel Colton, and the start across the desert was made against the advice of Kit Carson and other noted plainsmen. Hearing of the hardships of the Donner party, however, they hesitated at taking the route over the Sierras, and so, after waiting for six weeks in Salt Lake for the desert to cool off, they started southward.

Captain Hunt of the Mormon battalion of the Mexican war was engaged to lead them at a price of $1,000 for 100 wagons. Nearly 290 people were in the party at the beginning. About 50 miles south of Little Salt Lake they camped at a place where the trail branched, the left fork being the old Spanish trail and the right hand branch bearing the name of Walker's cutoff. The latter seemed shorter, from a study of the rude maps of the time, and about 100 wagons separated and started over this route. In a short time, Captain Hunt and the rest abandoned the Spanish trail and followed the lead of the others.

They soon found that they could eat the flesh of their cattle, and so a diet of oxen was begun, to continue until they reached California. These poor animals, scarcely more than skin and bones, were killed regularly, and the skin boiled until it was eatable. Possibly a pailful of blood was secured from each, and this made a blood pudding. By boiling the entrails, a dish on the order of tripe was made. There was not other food.

Three out of five water holes they reached contained alkali and so had to be passed by. Men and oxen alike dropped in their tracks, never to rise again.

According to the account of Roy Brier, husband of the "little woman," one man was left behind, unable to walk, and the party too weak to assist him. When "Providence spring" was reached, they went back to look for him — he had crawled for four miles on his hands and knees before he died. A second wandered away insane, a third fell dead without a groan, another staggered into one of the springs on the route and died with the first taste of water on his lips. When his veins were cut open, a watery fluid bearing a faint resemblance to blood flowed out.

One tragedy followed another on this trip through the desert. Some 800 miles north and east of Death valley, soon after the start, a 1,000-foot cliff was reached, where water had to be hauled up from below in buckets. Seeing no other way ahead, they decided to descend, lowering their wagons by ropes to the plains below.

Captain Hunt told them they were "going to hell," and refused to follow.

By Christmas day, when the Amargosa and Salt river on the edge of Death valley had been reached, the ox wagons had been cut down to carts, and then even these were abandoned and pack saddles made. Here they were overtaken by a party of Georgians who had been of the Jayhawker caravan at one time. Far away against the side of the mountains could be seen a tiny patch of snow, and for this the Georgians set out.

Two days later the Jayhawkers, nearly insane from thirst, caught up with them, to be revived by melted snow, which the Georgians had prepared. Leaving some of their cattle behind for the other party to eat, the southerners set out ahead over the mountains, later to meet their death at the hands of Indians.

Of all the party, young and hardy though they were, Mrs. Brier, a woman weighing only 115 pounds, and having three young children on her hands, was lees affected by the hardships than any of them. Her nerve and courage brought the rest through many a day when otherwise they would have given up in despair. Sometimes she saddled oxen for the weakest of the men, and at all times cheered them on.

Though they made but few miles every day, they finally emerged from the desert into the mountains at the head of the Santa Clara river, finding water but no food. Rev. Brier later wrote that their cattle were stampeded near here by a grizzly, all of the voyagers being too feeble to chase them.

On the morning of February 4, 1850, Colonel Colton and Tom Shannon, who had been in the Mexican war and knew the appearance of the Mexican haciendas, saw a red tile roof in the distance, and a little while later they met with vaqueros, who at first showed much fear. On understanding the plight of the party, they set out for the ranch house, while others went back to aid the rest of the party. At that it took from the middle of the morning to sundown to traverse the few miles to the ranch.

The hospitable manager, Jose Salazar, ordered calves and sheep slaughtered, and beef, mutton, frijoles, tortillas and other dishes were cooked in abundance. For several days the jayhawkers merely ate and slept, and then a general celebration followed their recovery. Two weeks more saw them on their way to the coast, their sufferings ended.

|