|

|

Where Once Was Water

Prehistory of the Newhall Ranch.

The people who buy the first homes in Newhall Ranch won't be the area's first residents. The first inhabitants arrived millions of years ago.

By Leon Worden

| Tuesday, August 18, 1998

|

Often, the displacement of prehistoric artifacts by a new housing project is met with a huge public outcry. Ironically, the most detailed information about a specific area often doesn't come to light until it is about to be developed. That's because developers are required to submit documentation about the area before it can be turned into a mall or housing tract. That documentation — the environmental impact report — includes a section on the area's cultural and paleontological background. Prepared by experts, the report often becomes the most thorough accounting of the area's past. This is certainly true of the documentation for the 19-square-mile region that is proposed to become the 24,000-home community of Newhall Ranch. In 1993, the Newhall Ranch Co., a division of The Newhall Land and Farming Co., retained the Ventura County-based firm of W&S Consultants to conduct a scientific survey of the area. The survey was conducted from 1993 to 1995. Archaeologists David Whitley of the UCLA Institute of Archaeology and Joe Simon headed a team that examined all pertinent archival records of the history and prehistory of the site, while paleontologist Rodney Raschke and others did the paleontological research. Then they went digging. Their report comprises the Cultural-Paleontologial Resources section of the Newhall Ranch EIR. It's more than 200 pages of mostly brand-new details on everything from the marine life that once populated the region, to the rise and fall of prehistoric man, to the Spanish conquest and the founding of the sub-mission at Castaic Junction. The information below is drawn from that report. In sum:

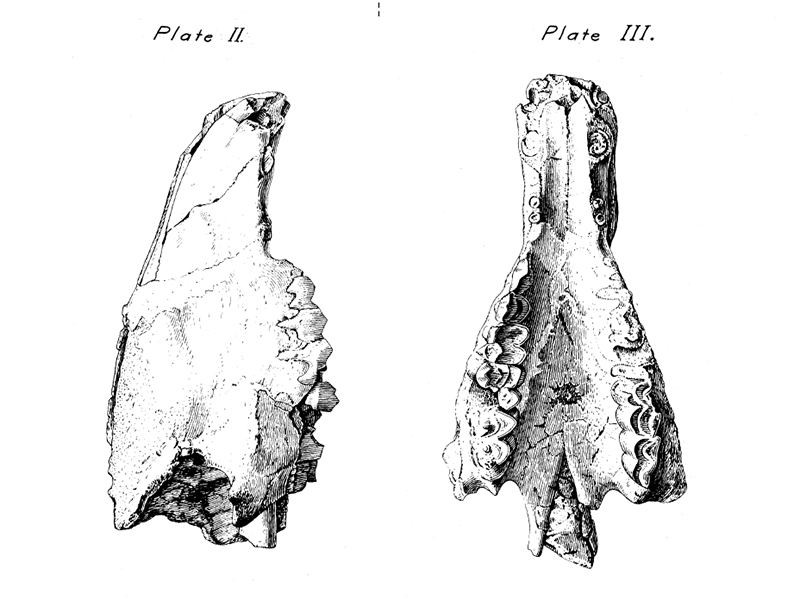

Newhall Ranch is underlain by rocks ranging in age from the late Miocene Epoch to present. The Modelo formation, to the south, is known for the well-preserved fish and bird skeletons, marine mammals, mollusks, plants and microplankton that were deposited there in the late Miocene, 8 million years ago. The formation yielded a fossil walrus, southwest and outside of the project area. As the water began to recede in the late Miocene and early Pliocene (8 to 4 million years ago), vertebrates and invertebrates were deposited in the shale and sandstone of the Towsley formation. East of State Route 14, outside the project area, this formation has yielded fossilized whales, sea cows and a distant relative of the walrus. Invertebrates and the occasional vertebrate were left behind in the Pico formation as the water got shallower and shallower, 4 to 2 million years ago. The end of the Pliocene saw the complete withdrawal of the ocean from the Santa Clarita Valley. The event is recorded in the Saugus formation, which in Simi has yielded vertebrates from the Pleistocene (1.6 million to 200,000 years ago) including extinct horses, large cats, dogs, elephants, turtles, peccaries (similar to wild boars), deer and sharks. Grading for the Valencia Commerce Center revealed an extinct relative of the zebra, among other things, in the Saugus formation. Raschke found the abundance and diversity of Saugus formation fossils in Newhall Ranch to be surprising. Little was found in the surveys of later deposits. A Bison tooth, probably less than 200,000 years old, was found just north of the project area. Raschke concludes that the oldest formations, Modelo and Towsley, have "high paleontological potential" but are not threatened because their exposure on the Newhall Ranch is limited to areas where no development will occur. The Pico and Saugus formations have both high paleontological potential and "relatively higher potential for significant impacts" by development. The newest deposits are only moderately significant, based on their relative scarcity, but development will have a "high" impact on them, the report says. Raschke recommends that a qualified paleontologist be retained to monitor excavations and salvage scientifically significant fossil remains when development occurs. Geological formations with a high potential, such as the Saugus formation, "will initially require full-time monitoring during grading activities." He recommends that samples of rock be collected periodically, before and during grading, and stockpiled for later scientific processing. He also recommends that specimens ultimately be given to a public, non-profit educational institution such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Over time, as animals made their adaptations from sea to land, oak woodlands cropped up where once there had been water. Fossil evidence reveals that the long, gradual "drying out" was spiked with shorter periods of dry and wet times, each lasting about 5,000 years. One extremely hot, dry period began about 9,000 years ago. It covered the western United States and caused the woodlands of Potrero Canyon and other mesas of the Santa Clarita Valley to recede to higher southern elevations. When the dry period ended about 3,500 years ago, prehistoric man migrated west. Whitley and Simon's survey team found eight instances of human habitation on the Newhall Ranch project area. Only three were camp sites — far fewer than the scientists anticipated, when compared to discoveries elsewhere in the Santa Clara River Valley. "We didn't expect this in a million years," Whitley said in a 1995 interview. "On 12,000 acres, we found just three camp sites. It's the lowest population this side of the Mojave Desert." The three sites were significant winter encampments that housed 20 to 30 people each. The other five discoveries included scattered artifacts with nothing below (the artifacts were collected by the archaeologists and preserved), a lithic (stone tool) work site, and a cache cave that had been looted before the turn of the century. All but one of the eight sites was a new discovery. The three encampments date primarily from the Middle Horizon (or Intermediate) Period, 3,500-800 years ago. One was used from 2250 BC to AD 940, another from 160 BC to AD 1160, and another from AD 236 to AD 808. The absence of evidence of early man after AD 1160 was also extremely interesting to the archaeologists. The disappearance coincided with the beginning of another long period of drought that swept the West. At one time, some 2,000 Native Americans populated the Santa Clarita Valley, but only about 1,000 remained when the Spanish arrived in the late 1700s — and none on the Newhall Ranch. Instead they were concentrated in areas to the west, at Camulos and Piru, and to the east, at Agua Dulce. Who were these earliest inhabitants of Newhall Ranch? Nobody is really sure. The Tataviam arrived around AD 450, but who preceded them is unclear. What is known is that they used manos and metates to grind hard seeds, and they used large spear points for big game hunting. Much more is known about the Tataviam, who occupied an area bounded by Piru on the west, Newhall on the south, the Liebre Mountains on the north and Soledad Pass on the east. They organized into a series of autonomous tribelets and spoke a Takic dialect of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic family, similar to that of the Gabrieleños of Riverside County and the Kitanemuks of the Antelope Valley. At Camulos, they mixed with the Chumash, who populated California's south coastal regions.

The Tataviam were hunters and gatherers. Women gathered sage, wild seeds, agave (century plant), juniper berries, acorns and other plant food, which comprised 80 to 90 percent of the Tataviam diet. The cruder manos and metates of their predecessors were replaced with mortars and pestles for pounding acorns into meal. They placed greater emphasis on hunting. The spear points of the past gave way to more accurate and convenient bows and arrows. No longer did they rely on big game; now they could hunt smaller, more plentiful game. New archaeological evidence sheds light on the trade patterns of the early Newhall Ranch inhabitants. The presence of shell beads would indicate a trade route to the coast, but since none were found on the site, Whitley and Simon suppose there may have been an ethnic barrier between the earliest Tataviam and their Chumash neighbors to the west. The presence of obsidian arrow heads and soapstone suggests that they instead traded with people in Agua Dulce and points east. The Tataviam practiced a form of shamanism similar to that of other early California residents, where a spiritual leader got in touch with the supernatural world through trances and hallucinations brought on by the ingestion of jimsonweed, native tobacco and other psychoto-mimetic plants found near rivers and streams such as the Santa Clara. (Such habitats also provided material for baskets, cordage and netting.) In A Guide to Rock Art Sites (1996), Whitley explores the meanings of Native American rock and cave drawings in Southern California and Nevada, similar to those found at Vasquez Rocks, which he says are primarily the work of shamans who recorded their visions so that they might better remember them. Whitley and Simon refer to Bowers Cave, outside the project area at the northwestern boundary of the Chiquita Canyon Landfill. Looted by two local teen-agers in 1884, it yielded the most extensive collection of Tataviam religious artifacts ever found. Most of its contents were taken to the Peabody Museum of American Ethnology at Harvard University, although some have since been scattered as far away as Australia. The archaeologists also refer to the old Tataviam village of Chaguayabit, of which they found no physical evidence. (Although it is not detailed in the Newhall Ranch report, portions of a Chaguayabit burial ground were unearthed in the late 1960s during the construction of the cafeteria at HR Textron, east of Interstate 5 on Rye Canyon Road.) The absence of any Newhall Ranch inhabitants after AD 1160 jibes with the first map of the area, drawn in Spanish in 1843. It labels the mountains of Newhall Ranch as lomas esterillas, or "sterile hills," no doubt because of their stark topography and dearth of human habitation. Whitley and Simon were accompanied on their excavations by representatives of the California Indian Council Foundation to ensure that the proper care and respect was taken in the handling and disposition of any remains found on the site. "Avoidance and preservation" are the primary methods the archaeologists recommend for protecting the prehistoric sites. In the unlikely event any new discoveries are made during grading, archaeologists would be called in. Whitley and Simon conclude that there should be "no unavoidable significant impacts" to the sites as long as their recommendations are put into action. "In fact, if mitigation is properly carried out, a positive impact on cumulative cultural resource information would occur; that is, mitigation measures would result in the acquisition of additional scientific information about the prehistory of the region, thereby serving to clarify our reconstruction of prehistoric lifeways, while the artifacts obtained from the sites during mitigation procedures would be preserved for future analysis and study." What does it all mean? In terms of preserving the paleontological and prehistoric resources of Newhall Ranch, the report presents a dilemma. Leaving the fossils and artifacts untouched would certainly preserve them. However, unless they are further excavated, they cannot be studied, and unless they are studied, no one can learn anything from them or know exactly what it is that should be preserved. As for the prehistoric artifacts in particular, Whitley and Simon recommend a course of action to protect them — taking into account the notion that the presence of only three significant encampments on almost 12,000 acres implies that all prehistoric sites could be preserved without seriously impeding development. Some inferences can be drawn that go beyond the preservation. For instance, the gradual drying out of the region over several million years and the inability of the project area to sustain human life in recent centuries suggests that water will be an issue long into the future. The study is a boon to historians. Not only did it directly result in the discovery of eight (seven new) instances of prehistoric habitation, but the 200 pages of new data expand their understanding of early life within the specific project area and, in their broader application, the Santa Clarita Valley. ©1998 Leon Worden • Originally published in The Signal. |

SEE ALSO:

Tick Canyon Camel (Maxson 1928)

Sand Canyon Whale

Castaic Bison (1950)

Canyon Country Oreodonts (Whistler 1967)

Newhall Ranch Bivalve

Sand Canyon Marine Fossils x3

Fish Canyon Scallops

Pico Formation 2011 (Squires 2012)

Marine Fossils, Newhall Creek x7

Pico Canyon x2

Marine Fossils,

Towsley Canyon x12

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.