|

|

Agua Dulce Man Preserves Tataviam Past

Future interpretive center at Vasquez Rocks to educate about early inhabitants.

By Katalin Szabolcsi

Originally published in The Signal | Sunday, October 29, 2000

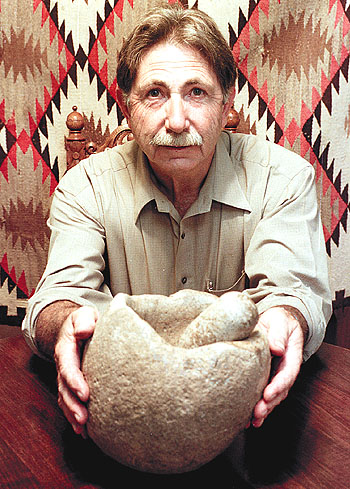

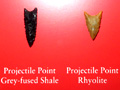

Objects can talk. In fact, they talk volumes if one knows how to listen. The home of Art Brewer of Agua Dulce is full of such objects — artifacts made by the Tataviam Indians hundreds of years ago. An amateur archeologist, Brewer has been collecting these artifacts for more than 30 years. "I don't dig for them myself," he said. "I've been living in this community for decades. People know me and know how much I care about preserving this area's history, and they bring these things to me. "They know I will take good care of them." Brewer's collection includes stone artifacts such as manos and metates (used to grind hard seeds), mortars and pestles (to pound acorns), arrowheads, spear points and small beads. He also has small clay objects that puzzle experts for two reasons: No one knows what they were used for and, according to archeological data, the Tataviam didn't even make pottery. Another curious piece in Brewer's collection is a stone ax, also found locally. Brewer was visited by Dr. John Johnson, curator of anthropology at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, who was very excited about the ax. "There were only three axes like this ever found in California," Johnson said, "including this. It is very interesting." Johnson said the ax is known as a "grooved ax" and is not native to California. Its origin is southern Arizona, and it was made by an Indian tribe there, the Hohokam. "This clearly shows extensive trade," Johnson said. Brewer agrees. "I think that Vasquez Rocks was an extremely important hub of interstate trade," Brewer said. "The artifacts found suggest that many groups of people came here periodically to trade. It is hard to go anywhere in California without passing through Vasquez Rocks." Then there is The Bowl. Found on Agua Dulce resident Mark Meyer's property in 1994, the wooden bowl "might be the most significant artifact ever found in the Southwest," said archeologist Dr. Charles Rozaire.

The 9 1/2-inch by 9-inch bowl is made of oak gall — an abnormal swelling on a tree caused by insects or disease — and it shows traces of several mendings. It had remnants of basketry on the top and bottom, and was coated with asphaltum inside, indicating that it might have been used to carry water. Meyer donated the bowl to the Vasquez Rocks Nature Center, but for lack of an appropriate storage facility it was given to the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society on a long-term loan in 1995. "The deal was, the VRNC would get it back as soon as our interpretive center was built," Brewer said. "But unfortunately this seems to be in jeopardy." Earlier this year Meyer reportedly took the bowl back, and his intentions are not known. Meyer did not return a phone message. Brewer's biggest fear is that "because of improper storage, its condition might deteriorate irreparably. "We (the Vasquez Rocks Nature Center Associates) would like to get it back and take good care of it," he said. "It is an important piece of history and should be on display for everybody to appreciate it." Brewer is president of the VRNCA, a non-profit organization formed in 1991 to build a Nature Interpretive Center at Vasquez Rocks, which was listed on the National Register of Historical Places in 1973 for its archeological and historical importance. "We collected signatures from 3,500 local residents and got a professional rendering by architect Dave Baumont for a small interpretive museum at Vasquez Rocks," Brewer said. "Then we presented the plans to (Supervisor) Mike Antonovich, who thought it was a worthwhile effort." The VRNCA held fund-raisers to get the word out about the project, and in 1998 the County of Los Angeles allocated $1.2 million from Prop. A funds to build an interpretive museum at the park. "No specific site has been picked yet," said Mike Sharp, head ranger at Vasquez Rocks County Park. VRNCA's mission is to educate the public about local history and nature, provide recreational opportunities and preserve the Native American sites at the park. The group intends for the Vasquez Rocks Interpretive Nature Center to be dedicated solely to local history — mainly to preserve and educate about the town's early inhabitants, the Tataviam. Under the tentative plans, the museum will host alternating displays of artifacts, research facilities, a re-created archeological excavation site for children to learn about "digs," and a small life-like Tataviam village setting where visitors can learn about food preparation, see how tools and clothing were made, and discover other cultural features of the tribe. "Preserving history should be the most important thing in the world," said Brewer. "'Without the past, there is no future,' my professor used say, and all I'm trying to do now is make sure our local history is properly preserved."

©2000 Katalin Szabolcsi & SCVHistory.com

|

Bowers Cave Specimens (Mult.)

Bowers on Bowers Cave 1885

Stephen Bowers Bio

Bowers Cave: Perforated Stones (Henshaw 1887)

Bowers Cave: Van Valkenburgh 1952

• Bowers Cave Inventory (Elsasser & Heizer 1963)

Tony Newhall 1984

• Chiquita Landfill Expansion DEIR 2014: Bowers Cave Discussion

Vasquez Rock Art x8

Ethnobotany of Vasquez, Placerita (Brewer 2014)

Bowl x5

Basketry Fragment

Blum Ranch (Mult.)

Little Rock Creek

Grinding Stone, Chaguayanga

Fish Canyon Bedrock Mortars & Cupules x3

2 Steatite Bowls, Hydraulic Research 1968

Steatite Cup, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x5

Ceremonial Bar, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x4

Projectile Points (4), 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig

Paradise Ranch Earth Oven

Twined Water Bottle x14

Twined Basketry Fragment

Grinding Stones, Camulos

Arrow Straightener

Pestle

Basketry x2

Coiled Basket 1875

Riverpark, aka River Village (Mult.)

Riverpark Artifact Conveyance

Tesoro (San Francisquito) Bedrock Mortar

Mojave Desert: Burham Canyon Pictographs

Leona Valley Site (Disturbed 2001)

2 Baskets

So. Cal. Basket

Biface, Haskell Canyon

2 Mortars, 2 Pestles, Bouquet Canyon

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.