|

|

Eyewitness to the 20th Century

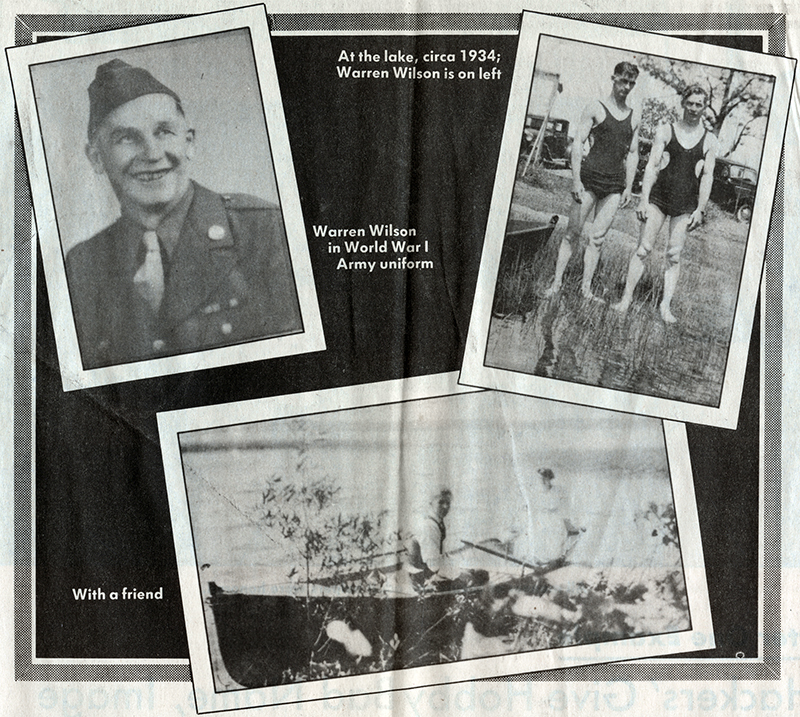

Warren Wilson: Veteran of 2 World Wars.

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Sunday, December 9, 1984.

|

Webmaster's note.

The 1918 William S. Hart movie, "The Border Wireless," although fictional, was based on the true story of the American effort to thwart Germany's attempt to use Mexican recruits to invade the U.S. over land during World War I — action in which SCV resident Warren Wilson was a real-life participant.

Men remember odd things about their first months of army service. Warren Wilson, a veteran of both world wars, remembers the lice. "I joined up in April 1918, just after the war started. They sent me to Grand Rapids and then to Columbus, Ohio. "The first military thing we did in Columbus, Ohio, was to pick dandelions off a lawn. We all got fatigues on, and every day we kept on until we were sent somewhere else. All we did was eat and pick dandelions. There was no military training at all there. "After about a couple of weeks of that, we were put on a train. We had been issued our winter clothing, what they called the olive drab — heavy winter coats and shirts and underwear and pants — and they sent us all the way down to Eagle Pass, Texas, on the Mexican border in our heavy military drab." The weather was hot in Texas, and Wilson and his companions were miserable in their heavy clothing. But things would get worse. "Before we could join our regiment, we were quarantined. We all were in one barracks in our heavy winter underwear, and after about a week, we all come down with crabs. They even infected our clothes. "The next thing they did to us was to take us down to the immigration station on the Mexican border. You had to take all your clothes off, take a bath, and put your clothes into fumigation. All our woolen clothes shrank, and we had the darndest time trying to fit each other after that. Even our shoes were shrunk." Finally, they were issued summer clothing and allowed to join the 3rd Infantry of the U.S. Army. The 3rd Infantry, along with the 1st and 2nd Infantries, had been formed under General George Washington to fight the Revolutionary War. When Wilson joined, the 3rd Infantry was the only one of the three left. "The 1st and 2nd Infantries had lost their colors in battle. When that happens, that's a shameful thing, because we look up to our colors. The colors are the flag, see? The colors are very guarded in the Army, because that's the thing that leads us. That goes first, before the men with the guns even, in the battle. "Even today, the 3rd Infantry does all the services around Washington, welcoming veterans, guard duty, guard at the Unknown Soldiers' graves at Arlington. "Anyway, our duty was to protect the Mexican border all the way from El Paso to Nogales, Arizona. The Germans had paid the Mexicans to join the German army, and they'd been drilled by German officers. They planned to invade the United States from Mexico during World War I. "There actually was a battle fought to keep them from invading the United States. That, you probably wouldn't read in a history book. It was kept quiet, because they didn't want to have people to get scared, see? "One night about 11:00, we got a call to fold up our tents and take all our equipment and get down to a train in one hour. We didn't know; we thought we were goin' across, of course. We didn't know until we got all loaded on the train and there was an Extra come out in the El Paso paper that there was a planned invasion of the United States at Nogales, Arizona. "They had artillery there, and they had cavalry, but they didn't have many infantry; that's why we were sent over. So, we sidetracked everything on the Southern Pacific and they sent us over. We got there just as the battle ended. "The way that battle ended was that the 10th cavalry (composed of black soldiers and white officers) made a charge. They were supposed to get off their horses and take up the line with the infantry, but they didn't do it. They went right into Mexico." Wilson said the 10th cavalry disobeyed orders because they wanted revenge for an ambush in Mexico which had killed most of their men. The ambush occurred during an expedition directed by Gen. John Pershing to track down Pancho Villa. "That is why they wanted to keep it quiet: because we weren't at war with Mexico. We weren't supposed to invade. We were supposed to stay on our side and protect from invasion. "They drove the Mexican army back about five miles and dug trenches. We stayed there to make sure they didn't try it again. We had guards on the water supplies and all the municipal things all the time in order to keep them from poisoning the water or something. So, we stayed there until the Armistice." * * * Wilson grew up in the little lumber town of Baraga, Michigan, on the shores of Lake Superior. "It was wild country, very wild. The wolves used to drive the deer into town. Wolves are too shy to come into town, and the deer knew that, so they would come into town to escape the wolves. "The lumberjacks used to go out in the wintertime and cut the trees down. And they'd stay out there in the camp for months at a time. But every once in a while, they'd get a payday and a couple of days to come into town. They were wild. They'd drink and fight and everything else until they got their money spent, and then they'd go out to the logging camp again and build up another stake. "Most of them were transient; they weren't married. The married men stayed in town and operated the mills. "My father was a painter and interior decorator. He never worked in the mill. He made a good living." His mother had emigrated from Germany with her family, who came across on the boat with four other families. They had obtained land grants while still in Germany and established a colony five miles inland from Lake Superior, calling it Falk Settlement after Wilson's grandfather. "I used to go out there when I was a kid and spend the summer with my grandparents. We'd help a little bit on the farm. They grew potatoes and oats and hay and wheat. They used most of it for themselves. "We had one doctor took care of all the needs — dental needs and everything else. My mother had seven children, and all but the last one were born at home by a midwife. No hospital in the town." Wilson left home at 18. He was working as assistant foreman in a leather factory when World War I broke out and enlisted over the protests of his employer. "I was patriotic. I was 20, and that was the thing to do for a man that age. They had what they called service flags they'd put in the front windows of the homes, and the family would put one star on the flag for each family member serving in the armed forces. My family had three. My sister was a Red Cross worker, and my brother and I were in the service." After the war, he got his job back, although his employers were German. "They got patriotic, I guess, during the war. Before the war, they were sympathizers with Germany." * * * "While I was in the Army, I sent pictures home. My sister gave them to a girlfriend of hers, and she began communicating with me, and I communicated back. When I got my vacation, we became engaged. "We had a daughter nine months and 10 days after we got married, and I became a pretty well-settled-down married man for about 13 years, until we had a disagreement and finally ended in divorce. I was a drifter for about two or three years until I met my honey settin' out there at the table. We've been married 42 years." * * * When the Depression hit, Wilson was working as a bus repairman. In those days, buses were made of wood. His wife operated an antiques store. Wilson lost his job, and since no one was buying antiques, they sold the store, bought 20 acres in the country and raised chickens all during the Depression. "We lived very good; we didn't want for anything. We sold chickens and eggs, and bought our flour, salt and coffee and things that we needed. We didn't have any luxuries; everything was plentiful, but there was no money. Potatoes were 10 cents a bushel, if you could get 10 cents. "Mostly it was trading then. For instance, I didn't have a team of horses. I would trade my labor to my neighbor, who had a team of horses, for him to do my plowing. Everybody just traded like that, because there wasn't much money in circulation." * * * When Pearl Harbor was bombed, Wilson was in Miami, Florida, at a family reunion, eating a big dinner. "I was mad, of course. Everybody was mad that Pearl Harbor was bombed. Everybody was figuring to get in and do something to get revenge on them. People were volunteering like wild. "A Japanese team of arbitrators was in Washington when the sneak attack happened. I don't know exactly down deep what the trouble was they were arbitrating about. I think it had something to do with trade. "Whatever it was, it didn't seem like it was enough to cause a war." After bombing Pearl Harbor, the Japanese "bragged that they'd be invading the United States and that they'd be in Washington, D.C., in one year." People believed war with Germany was inevitable before it was declared. "It was obvious we were going into it, and most people wanted to go into it, because of the way they were invading countries and the way they were treating the Jews. The methods of attack were brutal, you know, and there was almost a hate for Germany in the United States." Wilson tried to enlist and was turned down for medical reasons. But he was drafted shortly thereafter. He was 10 days short of 45, the cutoff point. He was sent to radio school, but before he finished the course, he was ordered to go to work in a defense factory. His wife, Helene, worked in a bomb factory. "You've heard of Rosie the Riveter?" she said. "Well, that's what the women were doing. They were working on drill presses and milling machines and riveting machines, making all these things that went into planes, right along with men." Asked whether people feared that Germany and Japan would win the war, Wilson said: "I don't think anybody figured that Japan or Germany would win at the end. Everybody that wasn't in the army worked on defense. The country was so behind the movement to win the war that there was no thinking that we'd lose it. "The thing that I remember most about World War II was them dropping the (atomic) bomb. I thought it was terrible, but I thought that it had to be done. While it killed quite a few Japanese, it saved a lot of American lives, because they didn't have to invade Japan proper. That would have been costly." After the war ended, Wilson operated a taxi company until 1959, when he became tired of being on call 24 hours a day. He moved to California, worked at Bermite for a few years, and then became a postal clerk. He retired at 70. Now 87, Wilson resides in Newhall with his wife and works at the American Legion. * * * You've seen a lot of changes. Which have impressed you most? "It's hard to say which ones. I've seen before electricity was in the homes. I've seen before indoor plumbing. I've seen board sidewalks instead of cement sidewalks, and I've seen dirt roads for the main streets of the town, before blacktop or pavement. "I remember the first electric streetlights they had, and I remember when car headlights were lit with a match. "I think one thing that impressed me more than anything else was television when it come in. We had our first television in 1956. I think that was one of the big changes in our life." Helene says she is most impressed with washing machines. "I can remember doing washing on a scrub board with two galvanized tubs. I washed sheets and everything in those tubs." Do you think the changes have been good? "I think a lot of the changes have been bad. Television is one thing. The young people learn a lot of bad habits from television, I think — especially crime. They learn to partake of crime from the television. "When the television first come out, these crime pictures were the thing. Of course, they had a battle on them. But it sure taught our young people how to conduct crime. I think that made a big change in the young people of America. "The biggest change in my life, though, was when I got married. We're going to celebrate our 42nd anniversary on the 12th or 13th of this month. We've been very compatible." What's your secret? "It's the second dance for both of us. I believe that probably helped a lot. We did have a few differences, you know, but we finally came to the conclusion that we..." Helene: "I think it's because we're so different." Warren: "Yeah." Helene: "We don't have the same traits at all." Warren: "Well, we are different, but we bear our differences pretty good. Give and take, that's what you have to do." Helene: "What percentage?" Warren: "Even steven." Do you have any advice for young people? "Young people should lay off of all this dope that's going around. That's going to ruin their lives, destroy them. "It's getting worse and worse. Younger and younger children are using it. That's destroying the mind and the body both. "They turn to it every little problem they have, and not only that, it seems like it's the thing to do with the young people, whether they have a problem or not." Do you think kids have changed since you were growing up? "They've changed plenty. They got too much money to spend, for one thing. Their allowance is too big, and this is where they're getting their dope. "When I was a kid, we had our little things we used to do; for instance, on Halloween we used to do tricks they don't do nowadays. But nothing we used to do affected our health and our education. "We had a school with a wood furnace, and we used to have to cut wood from the surrounding forest and pile it up behind the school in the summertime so we had heat in the winter. "One time we went up at Halloween and took all that wood that was in back and piled it in front of the entrance. The next day, we couldn't go to school. They made us pile all the wood back again that day. "About the worst thing we would do is we'd steal somebody's gate and put it up on top of the garage, or take their wagon and run it down the street into somebody else's yard, or tip over these old outdoor toilets. That was considered the highlight of our Halloween. "We used to have gangs, but we didn't do crime. We had a gang we called the Dirty Dozen. What we would do is — we would do little things like maybe steal a chicken or something and go out in the country. Take some potatoes and some bread and the chicken and build a little barbecue out in the woods and have a party out there. Maybe we'd build a little shack and that'd be our headquarters for our meeting. It wasn't like things there are today; there was no crime or anything connected to it. "Our parties were under supervision of the adults. We used to do a lot of singing at our parties, and later on we got to playing cards. This pinochle game had just come out, and that was the thing, to have pinochle parties and popcorn and sing, if the family had a piano, the old-time songs, like 'Don't Sit Under the Apple Tree With Anybody Else But Me' and 'Auld Lang Syne.' And the Christmas songs. Maybe somebody would have a fiddle, and if the home was big enough, we'd have a dance. "In the wintertime there were hayrides. They would go into the barn and throw a lot of hay onto a big rack, and everybody would take two or three blankets along with them. We'd hide in that hay and wrap the blankets over us. "And we'd take a team of horses on a sleigh and drive into the farm country about a mile to a farmer that would invite us. "The games we used to play out there were called 'Post Office' and 'Spin the Bottle.' "These Post Office games were a little wild. Lots of kissing. Sometimes they'd try to go a little farther, too. "The parties would last until about midnight. That was about the longest we stayed out, because it took a while to ride out there and ride back, and sometimes it would be snowing so bad, the horses couldn't pull the sleigh very fast. "That was about the height of partying that I did when I was younger, those sleigh rides. Everybody enjoyed them." What do you think: Were those the good old days or not? "They were. They were the good old days. Nothing like the good old days. We lived simple and well. No complications, much."

This is the sixth biographical profile of The Signal's series of "Eyewitness To The 20th Century." The series continues Wednesday.

Download individual pages here. Clipping courtesy of Cynthia Neal-Harris, 2019.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.