|

|

HISTORY OF THE SANTA CLARITA VALLEY BY JERRY REYNOLDS

[NEXT] [PREVIOUS] [CONTENTS] [SEARCH]24. Wordsmiths

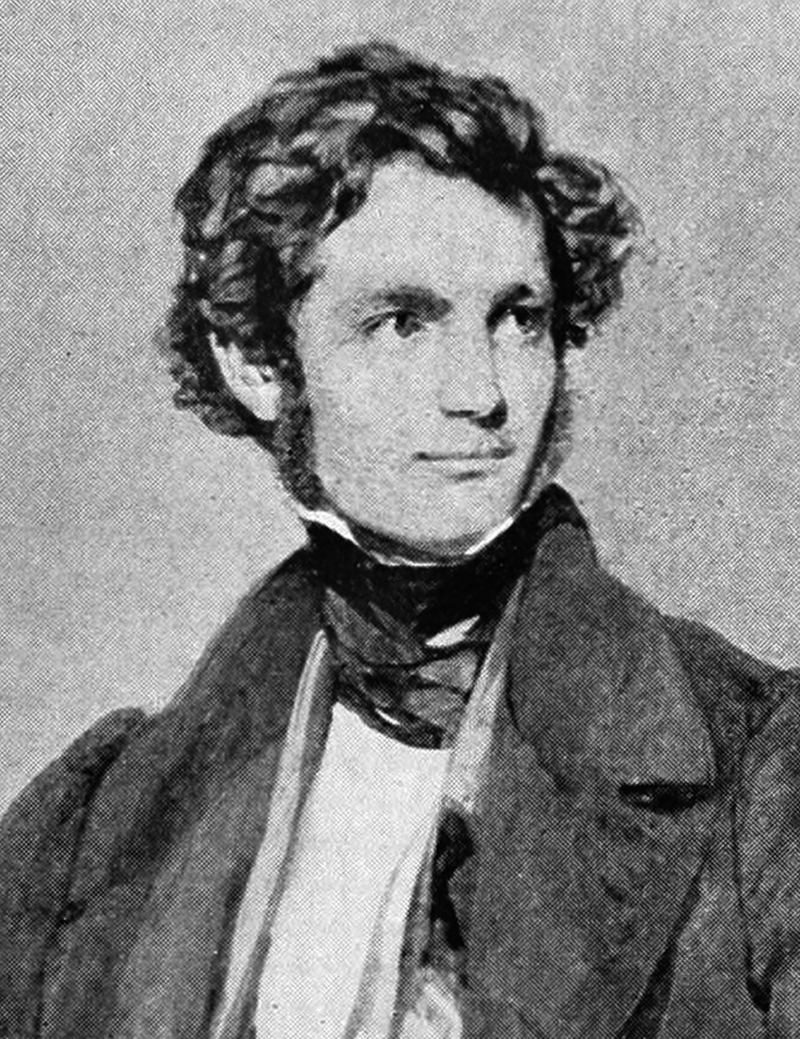

John Woodhouse Audubon.Several explorers and surveyors made their way through the Santa Clarita Valley and left some fascinating etchings and word pictures behind.

The first of these was John Woodhouse Audubon, who arrived at the head of a party of artists, scientists and cartographers during November, 1849. The son of famed ornithologist John James Audubon, he too was a naturalist, artist and explorer of some note. On his return home he published Audubon's Western Journal: 1849-1850, the record of his tramp through the Southwest from Texas to California.

Of Los Angeles he wrote, "This 'city of the angels' is anything else, unless the angels are fallen ones. An antiquated, dilapidated air pervades all, but Americans are pouring in, and in a few years will make a beautiful place of it."

Audubon stayed several days in Los Angeles, went on to San Fernando, and then camped at the base of Frémont's Pass. Early one morning his party started off:

"...Up an arroyo in tall, rush-like grass, where we had only bad water.... The hills are of a friable, whitish clay and sandstone, and after a very steep ascent [we] stood looking into a valley. From a hill higher than the one on which we were, swooped a California vulture, coming towards us until, at about fifty yards, having satisfied his curiosity, though not mine, he rose in majestic circles high above us.... We gradually descended into a beautiful valley to the Rancho San Francisco, and camped in sight of it with good water and plenty of wood. In the morning Rhoades killed the first black-tailed deer that any of the party has secured. We found it very good meat, and quite enjoyed it.... At the rancho we can usually buy fine, young cattle for from eight to twelve dollars."

On November 19, Audubon made his way up Castaic Creek to the area of Gorman, then through Grapevine Pass to the "Tulare Valley."

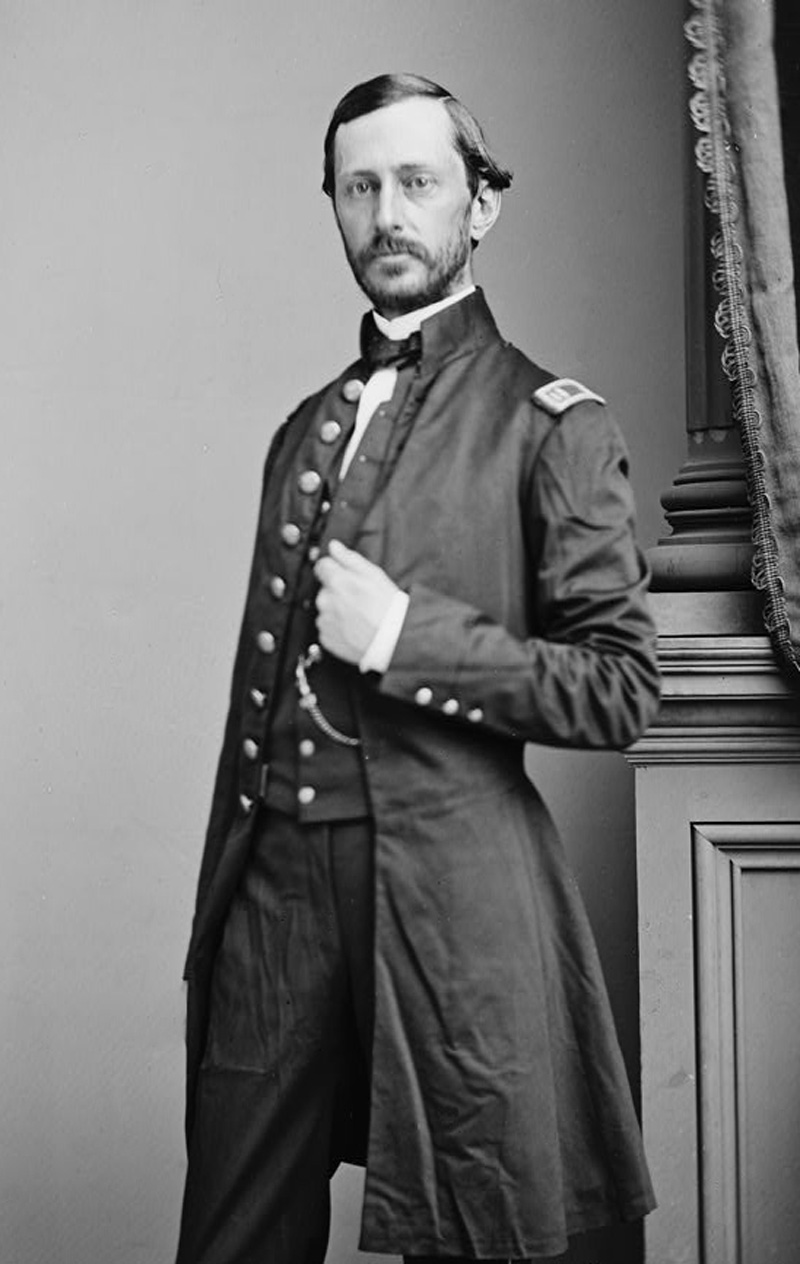

Lt. Robert S. Williamson.Four years later Lieutenant R.S. Williamson surveyed the Santa Clarita for Southern Pacific Railroad maps. He mentioned being lowered into the valley by ropes, then proceeded to scatter new place names like he was sowing seeds.

Not liking "Soledad Canyon," he changed it to Williamson Pass. Soledad Canyon it is today, but most of Williamson's place names are still with us, such as Tick Canyon — he was attacked by the little insects there — Placerita, Lake Elizabeth and Hungry Valley. It was Lieutenant Williamson who misspelled Cañada del Buque, rendering it Bouquet Canyon. For the first time, also, Castac was shown as Castaic, while Islay (Tataviam for "berry") became Hasley Canyon.

This same year, 1853, saw an appraisal of Rancho San Francisco. Two years earlier a board of land commissioners had been created by the U.S. government to approve land titles granted under the Spanish and Mexican regimes. The heirs of Don Antonio del Valle filed their petition in September, 1852. It was later confirmed.

The appraisers found the rancho to be worth twenty-five cents an acre "after taking into account the fact that a great portion of it consists [of] hills that are absolutely useless due to their sterility, and some of it containing good pasture." Cattle were valued at thirty dollars, horses at forty and sheep at four.

They concluded by saying, "Perhaps in the future there may be some change, either increasing or reducing said prices, for in this respect there is nothing really stable in our county."

©1998, SANTA CLARITA VALLEY HISTORICAL SOCIETY · RIGHTS RESERVED.

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.