|

|

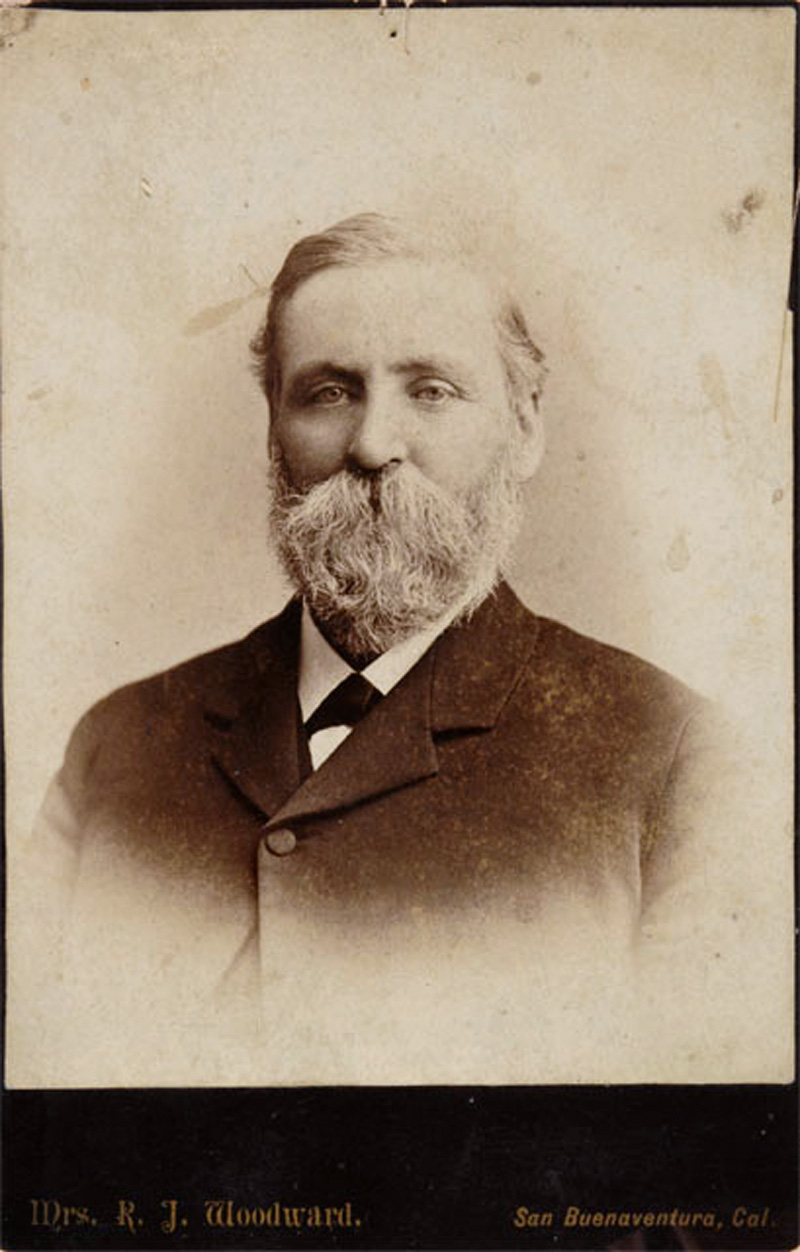

Biography of Rev. Stephen Bowers, A.M., Ph.D.

American Philosophical Society

n.d. (Earliest 1973)

|

Stephen Bowers (1832-1907) was a geologist, archaeologist, journalist and Methodist minister who maintained an interest in southern California, including area fossils and artifacts. His geological and archaeological work was financed by the Smithsonian Institution and the U.S. Department of the Interior. In 1997 a California archaeologist and Simi Valley, Calif., resident Arlene Benson published Bowers' field notes, collected by Smithsonian field ethnologist John Peabody Harrington, under the title "The Noontide Sun: The Field Journals of the Reverend Stephen Bowers, Pioneer California Archaeologist." Bowers was born near Wilmington, Ind., on March 3, 1832, to David and Esther Bowers. One of 13 children, the family moved to a farm eight miles north of Indianapolis when he was 1 year old. A studious lad, he walked or rode on horseback several miles to a small rural schoolhouse. Poor health kept him indoors as a child during the winter months. Realizing that he was not cut out to be a farmer, Bowers decided at an early age to pursue the ministry, and at 23 was ordained a Methodist minister, affiliated with the Indiana Conference. He was dispatched as a Methodist circuit rider 90 miles west of his birthplace in Lawrence County, Ind. In November 1856, just 10 months after beginning his ministry, Bowers married the 17-year-old Martha Cracraft from the farming community of Greencastle. Their first son, Hayden, was named for Bowers' hero, Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden (1829-1887, APS 1860), the leader of U.S. government surveying expeditions to 109 western territories in 1859-1860. From his youth Bowers became a lifelong collector of artifacts and geological specimens. Although he dedicated himself to the pastorate and later also pursued a second career as a newspaper publisher, his primary interest was always archaeology. With the exception of military service with the 67th Indiana Volunteers during the Civil War, Bowers spent several decades in pastoral ministry that took him to churches in Kentucky, Oregon and finally (because of his wife's failing health) to California. In 1874 he moved from his first pulpit in Napa City to the city of Santa Barbara. There Bowers found the lure of the Indian burial grounds on the Santa Barbara channel irresistible. In the summer of 1875 Bowers accepted an assignment as guide for several survey parties of the Army Corps of Engineers, working on both sides of the Santa Barbara channel. Wheeler's party included archaeologist Paul Schumacher, botanist Joseph Trimble Rothrock (1839-1922, APS 1877) of the University of Pennsylvania and Henry Wetherbee Henshaw, an ethnologist and ornithologist with the Smithsonian Institution. The Wheeler survey occupied all of Bowers' time, except Sundays, for three months, and Wheeler's notes make 16 references to him. It was through Henshaw that Bowers came to the attention of Smithsonian professor Spencer Fullerton Baird (1823-1887, APS 1855), who carried on an extensive 12-year correspondence with him. Through Bowers' excavations the Smithsonian would acquire thousands of California and Midwestern fossils and native American artifacts for its collections — 17 accessions over 29 years. Since no trained archaeologist had ever visited the native American burial grounds on the San Nicholas and Santa Rosa Islands before Bowers' 1875 excavation, he was the first to examine the remains of these settlements and remove the skulls, implements and artifacts for shipment to the Smithsonian and other museums, as well as to private collectors. Most of the skeletons and artifacts were from the Chumash tribe. During his three-year tenure as pastor of the Santa Barbara Methodist congregation at the corner of De la Vina and De la Guerra streets, he made one trip after another to the islands, usually accompanied by correspondent Simon Peter Guiberson of the Ventura Free Press and sometimes by his wife Martha and Dr. Lorenzo Yates of Centerville. Although methods of archaeological excavation were crude at the time, and Bowers was not the only untrained archaeologist doing field work, modern historians and archaeologists who are familiar with his activities generally regard him as "a meddler who destroyed fully as many artifacts as he preserved — and rendered the site scientifically useless, as well." They find his "flagrant disregard for orderly methods and his failure to preserve sites" inexcusable. It is unclear how many barrels of native American skulls, utensils and implements Bowers sent to collectors in New York, Washington, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and the District of Columbia, but the Smithsonian alone credits 2,200 to 2,500 of its native American relics to his excavations between 1876 and 1905. Harvard's Peabody Museum recorded 826, and hundreds made their way in public and private collections from Philadelphia to Los Angeles. No doubt, Bowers used questionable methods and was generally too impatient to exercise care in his excavations. Dr. Baird of the Smithsonian and Professor Josiah Dwight Whitney (1819-1894, APS 1863) of Harvard, two of his primary customers, were probably unaware of Bower's methods, although the former was definitely impressed by him. Bowers completed his excavations for the Smithsonian in September 1877 and moved to Indianapolis to accept a temporary call. Sometime in 1878 he returned to California and resumed his excavations. But after his wife and son Hayden died within months of each other in October 1879 and April 1880, he could not bear to continue excavations. Instead, he departed from Santa Barbara to launch a new career as a newspaper publisher in Beloit, Calif., Platteville, Wis., and Falls City, Neb. By October 1883 he had returned to California with a new wife Margaret Dickson to become publisher of the Ventura Free Press. Also serving a the Methodist pastor in the nearby town of Santa Paula, he launched another daily newspaper he called the Golden State. As a Prohibitionist and a Republican Bowers became involved in political controversy in his newspapers and in the pulpit, often teetering on the edge of libel. All the while he found time to continue digging artifacts in the Santa Barbara Channel. In 1899 the aging Bowers was appointed State Mine Examiner by California Governor Henry T. Gage. He had attracted the attention of one of the governor's aides by some earlier pamphlets he had written for the state mineralogist, as well as reports that made use of some of his geological contributions on rocks, fossils and oil-bearing strata. During his tenure Bowers endured the heat of the San Diego County desert to dig fossils in 13 different counties and also undertook an assignment from the U.S. Geological Survey to survey fossils around Riverside. Bowers enjoyed excellent health into his mid-70s and was accustomed to delivering two sermons weekly. However, in the final hours of 1906, while on a New Year's vigil, he fell ill and three days later suffered a stroke from which he died. He was survived by his wife Margaret, his son DeMoss, and daughters Anna Bailey and Florence Cooper. The American Philosophical Society's holdings of his letters show that he corresponded with major 19th-century American naturalists including Asa Gray (1810-1888, APS 1848) and Joseph Le Conte (1823-1901, APS 1873), as well as the Academy of Natural Sciences, the Museum of Natural History, the National Geographic Society and the U.S. Department of the Interior's Geographical Survey. Bowers also received an honorary doctorate from Willamette University in Oregon. The American Philosophical Society purchased a collection of 120 of Bowers' letters in 1973 for $160. The letters discuss "the fossils of southern California, as well as Indian artifacts, skulls, languages, ethnography, religion, etc." The society, headquartered at 104 South Fifth Street in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that "promotes useful knowledge in the sciences and humanities through excellence in scholarly research, professional meetings, publications, library resources and community outreach. This country's first learned society, the APS has played an important role in American cultural and intellectual life for over 250 years."

|

Bowers Cave Specimens (Mult.)

Bowers on Bowers Cave 1885

Stephen Bowers Bio

Bowers Cave: Perforated Stones (Henshaw 1887)

Bowers Cave: Van Valkenburgh 1952

• Bowers Cave Inventory (Elsasser & Heizer 1963)

Tony Newhall 1984

• Chiquita Landfill Expansion DEIR 2014: Bowers Cave Discussion

Vasquez Rock Art x8

Ethnobotany of Vasquez, Placerita (Brewer 2014)

Bowl x5

Basketry Fragment

Blum Ranch (Mult.)

Little Rock Creek

Grinding Stone, Chaguayanga

Fish Canyon Bedrock Mortars & Cupules x3

2 Steatite Bowls, Hydraulic Research 1968

Steatite Cup, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x5

Ceremonial Bar, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x4

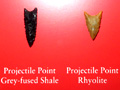

Projectile Points (4), 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig

Paradise Ranch Earth Oven

Twined Water Bottle x14

Twined Basketry Fragment

Grinding Stones, Camulos

Arrow Straightener

Pestle

Basketry x2

Coiled Basket 1875

Riverpark, aka River Village (Mult.)

Riverpark Artifact Conveyance

Tesoro (San Francisquito) Bedrock Mortar

Mojave Desert: Burham Canyon Pictographs

Leona Valley Site (Disturbed 2001)

2 Baskets

So. Cal. Basket

Biface, Haskell Canyon

2 Mortars, 2 Pestles, Bouquet Canyon

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.