|

|

The Haunts and Hideouts of Tiburcio Vasquez.

By WILL H. THRALL*

Historical Society of Southern California · The Quarterly · June 1948 · Vol. XXX, No. 2.

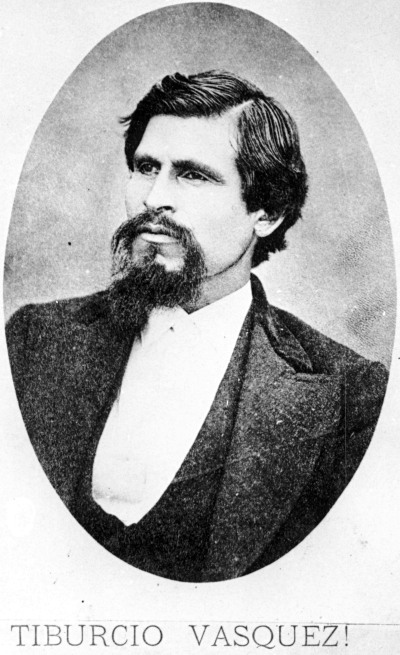

Tiburcio Vasquez | Click image for more

Webmaster's note.The HSSC Quarterly editor calls this "a story never before told in print" — and for history's sake, it might have been better if it stayed that way. "Wildly incorrect" is a term used by the foremost Vasquez chronicler, John Boessenecker, in his critique of this work and another by the same writer ("Vasquez, the Bandit"). See the Errata below.

Foreword

The great reign of terror which followed the gold rush days was not caused so much by the miscellaneous roughs who came into prominence as gunmen but by the organized raids of a succession of leaders who took to banditry to avenge some great injustice or the wanton murder of some member of the family. Such were the two who attained the most prominence, Joaquin Murrietta and Tiburcio Vasquez.

The bandit career of Murrietta lasted only 3 1/2 years but it was fast, furious and spectacular while it lasted and has come down to us as the most prominent and colorful of the two. That of Vasquez and his band lasted for 23 years, but there were spells of inactivity, some of several months, when the officers of the law and those who might be prospective victims wondered when and where he would strike next.

For 60 years the writer has been familiar with the Southern California, both valleys and mountains, in which Vasquez operated, has hiked his trails and camped in his campgrounds. From firsthand information, from many old pioneers and mountaineers who knew, from careful search of the records and from a file of information gathered during many years, this story is written.

It was well known that Vasquez was not a killer, that he repeatedly warned his followers not to kill, and his reluctance to take life, even when his own was in grave danger, was without doubt responsible for the remarkably few killings during his 23 years as an outlaw. The invariable report from those who knew him best was: "Oh, Vasquez was not so bad"; "There were many in those times who were far worse than he"; "Vasquez was a likable fellow and always a gentleman."

Vasquez the Bandit

Tiburcio Vasquez was keen, resourceful, a born leader. He hated the Americano with good reason and always in his mind was a thought, which had activated many of his race before him, that he could help get the Americans out and in some way regain California for Mexico.

At the age of 15 he lived in the town of Sonora [California], in the heart of the gold country; he had made himself a leader of the younger Mexicans and, feeling capable of taking care of himself under any circumstances, had grown bold and arrogant. He had a sister, beautiful and vivacious as young Mexican girls can be, and one night at a dance with him she resented the remarks of an American at the party. Vasquez, claiming that she had been insulted, demanded an apology and in the ensuing brawl stabbed the American.

Fearing the wrath of the Americans and certain retaliation, Vasquez and some of his young Mexican followers fled the town. Soon after this a robbery and murder at a mining camp nearby was laid to him and as he was no longer seen about Sonora it was said that he had joined the band of Joaquin Murrietta, then at the height of his career.

In the mining districts of those days killings were common and, as the victim was perhaps not too well thought of and often the aggressor, they were soon forgotten, so two years later, Nov. 17, 1852, we hear of Vasquez at a dance hall in Monterey where he was the life of the party. When a Deputy Sheriff tried to put him out, as he asserted for making too much disturbance, a shot was fired and the officer was killed. Vasquez was accused, though it was later determined that another of the party probably fired the shot. He was now a hunted man with a price on his head and, gathering together a band of his young comrades and others who were in bad with frontier law, he launched into a career of holdup and robbery which was to cost many lives and terrorize the southern half of California for more than 20 years.

The Last Three Years

The last three years of Vasquez operations were, with two notable exceptions, almost entirely in Southern California. In the Los Angeles area he had many places, strategically located, to which he could retire when hard pressed, among them Chilao and the great boulders of Mt. Hillyer; the gorge of Big Tujunga Canyon; the rough and wild area of Pico Canyon, west of Newhall; the famous Vasquez Rocks north of Soledad Canyon; and the rock-strewn mountainside north of Chatsworth, dominated by the famous Castle Rock.

East Chilao, now the site of Newcombs Ranch Inn, but then deep in the wilderness and little known, made an ideal hideout; the long, narrow valley of West Chilao and Horse Flat with its secret trail, both were excellent pasture for stolen horses, and the great rocks of Mt. Hillyer above Horse Flat furnished an impregnable fortress if hard pressed by the law. Vasquez made this his mountain headquarters for many years and through Chilao went a steady stream of horses, stolen in the San Fernando and San Gabriel valleys, brands changed or blotted out at Chilao, and then on to Yuma and the mining areas to the east and north.

Members of his band frequently stole horses from the United States government at Yuma, re-branded them at Chilao and sold them in the San Fernando Valley. It is told that one of his men once stole a pair of enormous mules, so well known for their size and strength that they dared not offer them for sale. That, after keeping them in the mountains for a time, they were finally taken into a secluded canyon and shot. The best and fastest of these stolen horses were always kept for the use of the bandits themselves.

It was said that Jose Gonzales was guard for the camp and stock, living in a little log cabin near the present site of Newcombs Ranch Inn; that he battled with and killed a big bear when armed only with his knife, and this gained for him the nickname of "Chillio," or as we today would say it, "Hot Stuff." In those days the area was known by that name but down through the years the spelling has been changed, by those who did not know, to the Chilao of the present time.

Vasquez Rocks

Vasquez had placed Clodovio Chavez in charge of part of the band operating to the north of Antelope Valley and they were stealing horses to be exchanged for those stolen by Vasquez band in the south, so that each could dispose of them with less chance of detection. It is told that their usual meeting place was that mass of up-ended sandstone and conglomerate located in the hills between Soledad and Mint Canyons a few miles west of Acton and long known as Vasquez Rocks or Robbers Roost.[1]

As one traverses the maze of narrow passages, twisting and turning in all directions between towering rock walls, many too narrow for even the passage of a horse, some leading entirely through, some to little rock-walled glades, many ending abruptly against a sheer wall and others at the edge of a cliff, high above the road, it is easy to believe even the most extravagant tales of its defense and of the daring and defiance of its master. In the old days the two-mile, rock-walled gorge of Escondido Canyon formed the easily guarded entrance to this natural fortress and this winding path through towering, fantastically eroded cliffs is considered by many the more interesting of the two.

Castle Rock

This enormous block of granite, one mile north of Chatsworth, was another natural fortress and its nearly flat crest, towering high above the west San Fernando Valley, gave an unobstructed view for miles around. Clustered about its foot was an Indian village, mostly built of adobe, its inhabitants all his friends, where he and has band could always find food and shelter and the law could never find a soul that knew him.

One of these old adobes was still standing in 1900 and in the loft was a litter of discarded parts of guns and saddle equipment. There is little doubt that at times Vasquez and some of his band hid out in this old adobe at the foot of Castle Rock and used its towering crest as a lookout. He well knew the trails through the deep, narrow canyons, ideal for hideout or ambush, and from the road's end he [could see] Pico Canyon and the Santa Clara Valley[2] and a clear route east, north or west.

The Big Tujunga

When it became necessary to go north or east Vasquez seems to have used Big Tujunga Canyon more than any other route. There was a fair road up this canyon for 14 miles, ending at a little flat where the Edison service road now crosses the stream and then known as Wagon Wheels Camp, from the front truck and wheels of an old wagon which had broken down there. The last three miles, above the present site of the flood-control dam, was through a narrow gorge with towering walls and many little side canyons, ideal for hideout or ambush, and from the road's end he had a choice of trails to Chilao, Little Rock Creek, or Vasquez Rocks beyond the Soledad.

Vasquez did some gold mining on the Tujunga and Mill Creek and there were other miners on both streams who, if not actually members of his band, were friendly with him. On Mill Creek, not far from the Monte Cristo Mine, he built an arrastra for crushing his ore[3]. The gin-pole, sweep and bed were still in good condition in 1916 when Phil Begue and Tom Lucas, two of the original Forest Rangers, burned everything combustible and washed the gravel caught between the stones of the bed, recovering about $6 worth of nuggets and yellow dust.

The Dunsmere Canyon Den

The advance post and hideout from which he raided the San Gabriel Valley and the whole Los Angeles area was in Dunsmere Canyon, north of Montrose in the south slope of Mt. Lukens. About a mile up from the mouth, where this canyon is split into two main branches, was an enormous oak tree so tipped toward the valley that its big top formed a perfect screen from below, almost completely blocking the canyon.

In back of this natural screen, from which a man or horse could be seen approaching a mile or more away, Vasquez made his camp. From here, by passes to the east, south and west, he could easily reach the whole of Los Angeles County south of the mountains. Back of this camp a faint trail led up and over the ridge to the Dark Canyon-Vasquez Canyon trail, with direct access to both the Arroyo Seco and Big Tujunga and a network of trails spreading across the mountains in all directions.

Many a time, while the posses were frantically searching the mountain trails and camps for this wily bandit, he was laughing to himself and his band right close to Los Angeles and the stock-raising valleys, safe from detection and with a ready getaway route if by chance they should discover his hiding place.

The Raid on Tres Pinos

Aug. 13, 1873, Vasquez and several of his band from the mining district about Sonora staged a raid on Snyder's General Store at Tres Pinos, Monterey County, killing Snyder and Davidson, the hotel keeper. This aroused a tremendous clamor for his capture and punishment and with the officers hot on his trail he scattered his band and, taking only Chavez, Levia[4] and two or three others with him, headed for Southern California. Vasquez had, for some time, been secretly intimate with Levia's wife Rosario and she was now one of the party.

Arriving at Elizabeth Lake, with a posse from the north hot on their trail and another heading in from Los Angeles, they left Rosario with a family there and fled through Vasquez Rocks to Little Rock Creek, headed for the mountaintop country which they knew so well. The officers overtook them in camp on the Little Rock, near the present site of the Little Rock Reservoir dam, where a few shots were exchanged with no damage to either party, and the posse, on unfamiliar ground, was afraid to follow in fear of ambush.

On returning to Elizabeth Lake the officers found that Vasquez had crossed the mountains, reached there ahead of them and, taking Rosario with him, had turned back to Little Rock Creek, somehow passing them on the way. There is scarcely a doubt that he took her to his hideout at Chilao; at any rate nothing further was heard of either for several weeks. Vasquez, on coming out of hiding, started Chavez out to help him recruit a new band and soon found himself at the head of a considerable force. These he sent out in twos and threes on small holdups and stock rustling expeditions.

Kingston Raided

It was now that Vasquez and Chavez began to plan the assembly of the whole band for another big raid, and the unlucky place chosen was the town of Kingston, on the Kings River in Fresno County. On Nov. 12, 1873, they too, with 14 others of the band, rode into this little town and, after tying up the 35 men in the place, plundered it to their hearts content.

The whole southern country was once more thrown into a furor of excitement, indignation and speculation as to what this law-defying daredevil would do next. The band was again scattered and Vasquez and Chavez spent several weeks with friends at Elizabeth Lake and in the San Fernando Valley. During the latter part of 1873 and early 1874 Vasquez and some of his band kept up small-scale robbery and stock rustling, until in February he called his forces together in Tejon Canyon, southwest of Tehachapi, 20 men answering the call.

The Owens Valley Stages

Inyo County and the highways to the south were selected as promising abundant loot with the least danger of reprisal, and the first strike was at Coyote Holes Stage Station on Feb. 25. Here they disarmed the Agent and seven men and compelled them to sit on the ground a short distance away, warning them that anyone seen on his feet would be shot. Vasquez then waited for the arrival of the stage from Los Angeles and robbed its passengers, among them the owner of the Cerro Gordo, Inyo County's richest mine.

Two of the Cerro Gordo freight teams arriving at this time, their drivers were also relieved of their valuables and compelled to join the colony on the hillside. Vasquez and eight of the band then rode into the Mexican settlement of Coso where he made arrangements to leave the Inyo field in the capable hands of his Lieutenant, Clodovio Chavez, while he, with part of his forces, left to care for his interests in Los Angeles County. His next job to attract public attention was only two days later when he and Chavez, traveling alone down Soledad Canyon, met and robbed the Los Angeles stage and passengers on the road between Mill Station and Soledad, following which they hid from the fast-moving posse in the labyrinth of Vasquez Rocks.

Now the manhunt was on again in earnest. Sheriff Morse of Alameda County arrived with 15 picked men to assist Sheriff Rowland of Los Angeles County and his deputies, and every wile that training and long experience could suggest was tried, but no Vasquez could they find, and they finally decided that he had gone back to his old haunts in Monterey County. It was later proved that he was never far from Los Angeles, but in the hills near Newhall, at Castle Rock near Chatsworth, or at the Dunsmere Canyon hideout, very likely at all three, and at all times he was immediately informed of every move of the officers of the law.

The Repetto Ranch Raid

Then came the raid which convinced the people that they were not safe from him, even within the city of Los Angeles, and soon led to his capture, trial and execution, the robbery at the Repetto Ranch, in the hills south of San Gabriel and a few miles east of the city. On the morning of April 15, 1874, Vasquez and four of his band raided the ranch home of Alexander Repetto, a sheep raiser, located near the crest of the hills just to the west of what is now Garfield Avenue in Monterey Park. His information service had brought in the news that Repetto had lately sold a bunch of sheep and had a considerable sum of money on hand.

Repetto, tied to a tree and threatened with death, finally convinced the bandits that the money was not hidden on the place but that all that remained, about $500, was in the Temple and Workman Bank in Los Angeles. Knowing well the desperate man he had to deal with and fearing for his life, he signed a check for the $500 and his nephew was dispatched to Los Angeles with instructions to bring back the cash without telling anyone, and soon, or he would find his uncle dead.

Arriving at the bank the boy insisted that he must have the money, and quickly, and the bank officials, keyed to the hair-trigger times and suspicious of the situation, immediately notified Sheriff Rowland. A posse, under Deputy Sheriff Johnson, was quickly organized and on its way but the boy, fearful for his uncle's life, beat them to the ranch by half an hour, paid over the ransom which, it is said, was all in gold, and before the posse reached the ranch the bandits were well on their way to those mountains that had always furnished them refuge.

The Escape Route

Two teamsters for a Los Angeles hardware firm had that morning delivered to Devils Gate on the Arroyo Seco a load of water pipe for the Indiana Colony (now Pasadena) and on their return trip met Vasquez and his men near Sheep Corral Spring (now Brookside Park). Well knowing that a Sheriff's posse was hot on his trail, the daring bandit took time to relieve them of what money they had and took from one a valuable watch which was returned to him after the capture.

Proceeding on to Devils Gate, the bandits found there a party of 15 prominent Colony men at work on their water supply. Telling them who he was, which was probably not necessary, he went on up the canyon without molesting them and, turning up the Dark Canyon trail, hid his loot, or a part of it, in an old stone wall about half a mile up this canyon. He was now on familiar ground, headed for Vasquez Canyon and the Big Tujunga, on a trial which had been his getaway route many times before.

Sheriff Johnson and his posse followed to a point where the trail crossed the old Soledad Road grade, and as it became dark both pursuers and pursued went into camp, the posse at the road grade and Vasquez and his men at a grassy nook just below the crest of the divide, only a mile apart. Vasquez stated after his capture that several times they could have easily killed all in the posse, but that he restrained his men, telling them that they would have every man in Southern California who could shoot a rifle on their trail.

With daylight the chase was on again, the posse following the crest of the divide, but from the reports it is likely that they followed the road grade rather than the trail, anyway finally turning back because they feared an ambush in the rough country ahead. Now the bandits were on a part of the trail that was in places very hazardous and nearing the Big Tujunga, with that big, open canyon floor and good going in plain sight, they had the misfortune to lose a horse over the cliff where the trail skirts too closely the rim of Apollyon Gulch.

The saddle, retrieved at this time or at some later date, was carried some distance from the scene of the accident and again abandoned. In 1883, nine years later, when Phil Begue, pioneer settler of the City of Tujunga, was a boy of 16, on one of his many hikes through the area, found the saddle and still in the holster an old revolver with the initials T V cut into the barrel. Phil became one of the first and best known of the Rangers of the old San Gabriel Timberland Reserve and this gun one of his treasured possessions.

Lost Again as Usual

When Sheriff Johnson and his posse abandoned the chase on the divide between Arroyo Seco and Big Tujunga, he led his men as speedily as possible through the La Cañada Valley to the mouth of Big Tujunga Canyon, hoping to block that route of escape before the bandits could reach it. As no one found in that vicinity would admit having seen them, it was decided that they must have gone up the canyon, headed for one of their several hiding places in that wilderness top country. So Johnson and his posse took up the trail until, after going over 20 miles, they met someone they could trust who assured them that Vasquez definitely could not have gone through.

All of this time, while the officers were getting farther off the route, Vasquez and his party were hurrying west along the foothills toward Fremont Pass and a safe retreat. By a trail which the officers had reported to be impassable but with which they seem to have had little difficulty, they had beaten the posse to the mouth of Big Tujunga and that night, the 16th of May, found food and shelter with friends in the valley.

Long before daylight, the morning of the 17th, they were on their way, by roads and trails with which they were familiar, west along and through the foothills toward Fremont Pass. Avoiding the too public Pass, with its Toll Gate and Stage Station at either end, they crossed the divide just to the east by Grapevine and Ellsmere [Elsmere] canyons and were seen early in the morning of the 17th, headed north near Lyons Station — and it was so reported to Sheriff Rowland[5].

They were probably headed for Pico Canyon where, in a little settlement of Mexicans and Indians, they would find friends and shelter. From here they could safely cross the Santa Susana Mountains to the Indian village near Castle Rock and then across the San Fernando Valley and Santa Monica Mountains where they finally, after a leisurely three weeks' trip, reached the ranch of Greek George, near the mouth of Laurel Canyon. This was their probable route and the very good reason why the officers lost all trace of them.

Many Friends and Lookouts

There were many in the outlying areas of Los Angeles County whom he had befriended in one way or another, some who were, or had been, members of his band; some who dared not give him any but the best information they knew because the officers of the law were unable to furnish them protection.

The old stage road from Los Angeles to the north went through Cahuenga Pass, passed near the San Fernando Mission, through the canyon which is now the site of the San Fernando Reservoirs[6] and crossed the mountains by Fremont Pass. At Lyons Station, just north of the Pass, Vasquez sometimes attended the dances — and with no lack of partners, as there was always competition among the ladies because, as they said, he was a wonderful dancer and always a gentleman. Then there was Sala's Station, just south of the Pass, in the present site of the Upper Reservoir, where it is said he sometimes spent the night.

Lopez Station and its popular hosts Geronimo and Catalina Lopez are often mentioned in the stories of those times, and Vasquez sometimes stopped there for a meal. This station was about a mile north of the Mission on ground now covered by the water of the Lower Reservoir. Here Geronimo Lopez had purchased about 20 acres of land, had improved it with orchard and vineyard and a large adobe home, which soon became Lopez Station to accommodate those who rode the stage lines and other travelers between Los Angeles and the north. Soft beds and excellent food soon made this a popular place and many prominent travelers of those days were proud to say "I stopped last night with Lopez."

Even at the Hacienda of General Andres Pico, next to the Mission San Fernando, Vasquez was welcomed at times, and there is a story. In the spring of 1874 Charles Maclay and George K. Porter purchased the north half of the San Fernando Valley and some of the adjoining hill country, 56,000 acres in all, for about $96,000. Overtaken by darkness one evening in April and being near the Mission, they stopped for the night at the Pico home where they were quartered in a large room with one remaining vacant bed. After they had retired, another traveler was brought in for this bed, but come daylight the next morning he had already gone. Curious to learn the identity of their fellow lodger, they asked General Pico.

"Why, that was Tiburcio Vasquez," he replied.

"Vasquez the bandit?" they questioned.

"Si, Senors, he whom you call the bandit."

"Do you extend the hospitality of your house to such as he?"

"Si, Senors, for he is my friend. He has many times protected me and my property from those who are worse, much worse. He has promised that no harm shall come to the valley from he or his band, and no harm has come, Senors."

Then there was Jim Heffner at Elizabeth Lake, Geronimo Lopez at San Fernando, Pedro Ybarra in the Big Tujunga Canyon and many others whom Vasquez had befriended or protected in some time of trouble. It would have been hardly safe to refuse him information, under the circumstances and in those times, or to tell him anything but the best they knew.

The Last Days

And now we come to the last days of this outlaw who had terrorized the southern half of California for 23 years and claimed, it may well be truthfully, that he had never killed anyone. The ability of the bandits to go and do as they pleased and the apparent inability of the law to protect was seriously affecting the growth and prosperity of the whole Los Angeles area. The news had gone forth throughout the nation that life and property were not safe from them, even within the city.

The press of the City of Los Angeles was warning that the bandits could, and likely would, raid the city itself unless desperate measures were taken to discourage them. The officers were taking desperate measures, but reports were so wild, conflicting and incorrect that they could not tell who or which to believe and they were well aware that every move of the Sheriff or any of his principal deputies was immediately relayed to Vasquez.

So when it was reported to Sheriff Rowland that Vasquez was living at or near the adobe home of Greek George, on Rancho La Brea[7], he made no move for several days, while instructions were going out to a few carefully selected individuals to accidentally meet at a certain place at a certain time.

The Greek George Ranch

In those days all of the high ground south of the hills and west to the Pacific was comparatively open country, with here and there clusters of trees about some spring or along a little water course. In a very few places, where there was natural water, there were crude habitations. All of the low, flat lands to the Baldwin Hills and west to Venice and Playa del Rey were covered with swamp or willow woods. The Greek George home, partly built of adobe and part of rough boards, stood on a natural terrace, near the foot of the hills, at about the present intersection of Kings Road and Fountain Avenue. A short distance back of the house and between it and the hills there was a little used road leading from the San Vicente on the west, across the Rancho La Brea and into the city, then centered about the Plaza 10 miles to the east.

In front and a short distance from the house was a spring which furnished their water, and growing around the spring a thick grove of willows in which the bandits had tethered their horses, partly hidden, and no doubt where they slept also, being safer than in the house. Through the canyons and over the hills to the north there were trails, known to few except the natives, which furnished safe access to the San Fernando Valley.

The Trap is Sprung

At 1:30 on the morning of May 15, 1874, Sheriff Rowland's specially chosen posse was gathering at the Jones Corral on Spring Street and proved to be Under Sheriff Albert Johnson, in command, Major H.M. Mitchell, W.E. Rogers, J.S. Bryant, Emil Harris, B.F. Hartley, D.K. Smith and George A. Beers, special correspondent of the San Francisco Chronicle. Soon they were in the saddle and on their way, following a route along the hills to Nichols Canyon and a little up the canyon to a Bee Ranch belonging to Mitchell, where they arrived about 4 a.m. in a fog so thick that visibility was practically zero.

From a ridge on the west, as the fog cleared, they had a clear view of the Greek George place and, near the spring, could see two gray horses, one of which they were quite certain was the speedy gray on which Vasquez had made previous escapes. A horseman was seen to leave the house and Mitchell and Smith were detailed to follow him, but the two grays still remained, and it seemed almost a certainty that Vasquez and one of his band were there, possibly more of them hidden nearby.

While planning the attack, and as they were about ready to start, two Mexicans with an empty wood-wagon drove into the canyon from the direction of Greek George's. The deep, high sided wagon box was ideal for their purpose and the driver and his outfit were familiar figures on the road, so threatening the two with death at the first false move, the six climbed in, lay down on the floor, and ordered them to drive back on the road passing in back of the house.

On reaching it they jumped out and surrounded the place without an alarm being raised, burst in the door and found Vasquez at breakfast. Attempting to escape, he jumped through the kitchen window and ran for his horse but was stopped before reaching it by a rifle ball through his shoulder and a charge of buckshot. Wounded in many places and thought to be dying, he was loaded into a wagon borrowed from the nearest ranch and with the other bandit, a young Mexican who had lately joined the band, was taken into the city.

It was found that he was not in a serious condition for all of his many wounds and in due time he was returned to Monterey County where he was tried, convicted, and hanged at San Jose on March 19, 1875. And the Judge who sentenced him to death stated that he did not believe him guilty of the crime for which he was to be hanged.*

*The Judge's sentence delivered in no uncertain terms hardly bears out this last statement. —Editor (J. Gregg Layne).

Errata.From Boessenecker 2010:370-371:

An enthusiastic and oft-quoted writer about Tiburcio Vasquez was Will Thrall (1873—1963), a popular Los Angeles explorer, chronicler, historian, and protector of the San Gabriel Mountains. Unfortunately, some of the Vasquez "history" he compiled was patently false. Thrall, in an effort to demonstrate a strong Southland connection with the bandit leader, claimed, "The last three years ofVasquez operations were, with two notable exceptions, almost entirely in Southern California." That, of course, is wildly incorrect, as Tiburcio spent only a few months in 1873 and 1874 in Los Angeles County. Thrall created a busy life for Vasquez in the San Gabriels. He had him running a gold-mining operation in Big Tujunga Canyon and building an arrastra for crushing ore. He claimed that Vasquez hid out in Dunsmore Canyon in the San Gabriels and at an Indian village north of Castle Rock, near Chatsworth. He created an extensive horse-theft ring, in which Vasquez stole animals from the U.S. government at Yuma, Arizona, drove them to Chilao, in the San Gabriels, and sold them in the San Fernando Valley. Why the U.S. government would have herds of horses in Yuma he did not explain. Nor is there any contemporary evidence that Vasquez ever set foot in Chilao. What is known is that the only time he fled into the San Gabriels, following the Repetto robbery, he needed a guide to lead his band. When the guide failed to appear, Vasquez got thoroughly lost and was almost trapped. This is not indicative of a man who had spent years living in the San Gabriel Mountains. Oddly, Thrall does not even mention two Los Angeles County locations that Tiburcio actually visited — Vasquez Creek and Piedra Gorda, now known as Eagle Rock. He seems to have compiled folk tales and legends and failed to adequately consult contemporary published accounts, of which there are many. Thrall's fictions have been widely accepted, and tourists to this day visit Chilao to see Tiburcio's hideout.

Webmaster's Footnotes.

- Take the Escondido Canyon Road exit off of State Route 14 in Agua Dulce, in the northeastern Santa Clarita Valley, to get to what is now Vasquez Rocks County Park.

- The Little Santa Clara Valley, i.e., the Santa Clarita Valley.

- Arrastra mining is an early method of crushing granite or quartz from the mines to release the gold veins trapped inside. Typically a horse or mule was roped to the end of a horizontal wooden beam that supported a huge stone wheel. The other end of the beam was attached to a pole in the center of a circular pit. The beast pushed the beam around the circle, while the stone wheel crushed the rocks beneath it.

- Commonly spelled Leiva, first name Abdon.

- Grapevine Canyon is unrelated to "The Grapevine;" it is roughly at the confluence of today's Interstate 5 and State Route 14. Lyons Station was where Eternal Valley Memorial Park is today.

- To the immediate west of the Roxford offramp off of Interstate 5.

- In present-day West Hollywood.

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.