Wreckage of Western Airlines Flight 23 which crashed into a 6000 foot high mountain peak 12 miles south of Gorman on November 13, 1946.

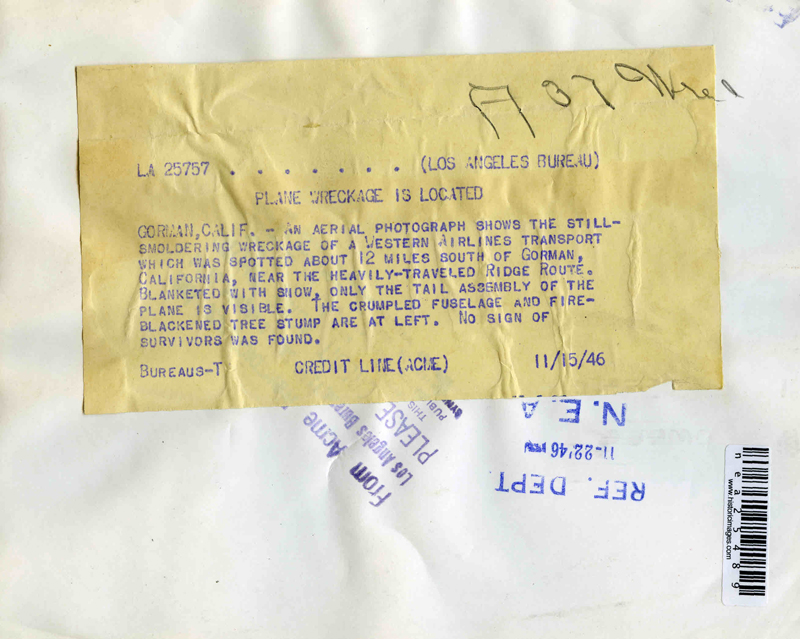

ACME wirephoto, 7"x9". Original cutline reads:

LA 25757 — — — (LOS ANGELES BUREAU)

PLANE WRECKAGE IS LOCATED

GORMAN, CALIF. - An aerial photograph shows the still-smoldering wreckage of a Western Airlines transport which was spotted about 12 miles south of Gorman, California, near the heavily-traveled Ridge Route. Blanketed with snow, only the tail assembly of the plane is visible. The crumpled fuselage and fire-blackened tree stump are at left. No sign of survivors was found.

Bureaus-T Credit Line(ACME). 11/15/1946

Story of Western Airlines Flight 23 Crash by Don R. Jordan

The DC-3/C-47 type aircraft was one of the most popular and reliable passenger aircraft of its day. More than 13,000 were built, and hundreds are still flying in several countries around the world. It is not uncommon to see an old DC-3 sitting on the back ramp at many smaller airports around the country. Some are used for skydiving activities or nostalgic tourist flights, while others sit derelict in the elements awaiting their ultimate fate. Designed and descended from the DC-1 and DC-2 of the early 1930’s they were intended for use by the commercial airline business. But, during World War II the DC-3 received the designation C-47 by the military, and was used around the world in cargo or troop transports roles. After the war, hundred of these old war birds were sold to the airlines for conversion to passenger carrying, revenue generating airliners. It was a task that suited them well, and once again made the airline companies profitable. Because so many thousands of these aircraft were built, and later converted by the airlines, it is only expected that more than a few would ultimately come to grief somewhere along their many routes. Many very famous and important people, including actress Carol Lombard, and singer Ricky Nelson would parish in DC-3s accidents.

Flight 23 was one such converted military transport. It now carried the civilian registration number of NC18645 under its wing and on its tail. It would begin its last scheduled route trip on November 12, 1946 from the passenger terminal at Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada, with a intended destination of Burbank, California, USA. It made five regular scheduled stops in Montana and Idaho, before landing for a layover stop at Salt Lake City, Utah. In Salt Lake the aircraft and equipment were given a routine inspection by company mechanics. Only some very minor discrepancies were noted, so the aircraft was released for further flight. Salt Lake was also a crew change point on this route. When Flight 23 departed Salt Lake City the flight crew was Captain Gerry Miller and First Officer Theodore Mathis. Back in the cabin with the sleepy passengers was stewardess Joan Fauntleroy. On the day of this accident Captain Miller, age 34, had more than 4,885 hours of flight time, with over 4,000 hours in DC-3 type aircraft alone.

While at cruise altitude north of Las Vegas, Nevada Miller called the company control dispatcher in Burbank by radio to report that the right engine was running a little rough on one magneto. Following a discussion with dispatcher W. D. Shugg in Burbank, it was decided to have the station mechanic in Las Vegas inspect the engine before the flight resumed. Arrival in Las Vegas was at 12:18 a.m. Once on the ground the mechanics checked the engine, and then released the aircraft for further flight. The aircraft was also refueled with 520 gallons of fuel. Departure for Burbank was at 1:45 in the morning on November 13th.

Due to inclement weather along the remaining route the following flight plan was issued to Captain Miller:

“Standard Instrument Departure from Las Vegas, cruise at 10,000 feet en route to Newhall, Calif., Standard Instrument Approach on the Los Angeles radio range station, further clearance expected over Los Angeles.”

At 2:35 in the morning, while the aircraft cruised between Las Vegas and Newhall, the Burbank dispatcher called Capt. Miller on the radio to inquire about the performance of the right engine. Miller reported that the engine performed perfectly at takeoff and climb power settings, but the left magneto on that engine was cutting out a little while at cruise settings. It was no cause for alarm, so the aircraft continued along the route. Miller was also informed that the Newhall radio range transmitter was out of service due to modifications being performed.

As the aircraft approached the Palmdale radio range Air Traffic Control (ATC) issued an amended crossing altitude for Newhall. Miller requested to remain at 10,000 feet, but due to conflicting southbound traffic the flight was assigned to cross over Newhall at 8,000 feet (msl). There are two 8,000-foot high mountain peaks in that same general area, and the Newhall radio range was out of service. It was a dangerous situation! With no ground radio transmitter to establish an accurate crossing, Miller would have to estimate his time when over the Newhall radio. It was not a situation any pilot would willingly attempt when flying on instruments at night in mountainous terrain. Miller wisely rejected the clearing, but later accepted a 9,000-foot crossing altitude instead.

The new ATC clearance called for Flight 23 to cross Newhall at 9,000 feet, then turn south and begin a descent so as to arrive over the Los Angeles radio range, and clear weather, at 4,000 feet. From there he would fly visually on the approach to the Burbank airport. This instrument procedure had worked thousands of times for other aircraft performing instrument approaches into the Los Angeles area airports. But it would fail Captain Miller and Flight 23 in a most catastrophic way at approximately 3:41 in the morning on November 13, 1946.

At 3:24 a.m. Miller reported by radio that he was over the Newhall station at the required 9,000 feet. Actually this was only an educated guess by Miller. It was based on his known time over the Palmdale radio, combined with the elapsed time and heading. This practice of determining position is called Dead Reckoning. And this time, due to factors he was not aware of, Miller was dead wrong.

A crosswind of high velocity existed which was unknown to Miller, and was not shown on any of the weather forecasts charts. This high velocity crosswind was encountered after leaving Palmdale, and while on the course for Newhall. This strong wind had been pushing the aircraft steadily off course to the north every since it left the Palmdale area. Now, tragically, instead of being over Newhall as expected, Miller was actually some twenty-five miles north of the position where he thought he was. To make matter worse Miller followed his clearance as directed and turned south. Then he began to descend to his next assigned altitude of 4,000 feet.

At 3:37 a.m., while descending from 9,000 feet, Miller copied his last clearance for the visual approach to Burbank. He was to report over the Los Angeles radio station, and then execute the normal visual approach to Burbank. He was also to report when leaving 4,000 feet, and to report when he had the Burbank airport in sight.

No doubt the passengers and crew were at that moment preparing for a normal landing at the Burbank terminal. It had been a long night, and mostly likely many of the passengers were still fast asleep in their seats. Up front the crew expected at any moment to see the soft glow of lights from the many towns and cities in the Los Angeles basin come into view. But it was not to be.

It is likely, in the pitch dark of the night, that neither crewmember saw the approaching 6,000-foot high mountain peak looming just a few miles directly ahead of their descending aircraft. Impact came at approximate 3:41 a.m. just 100 feet below the summit near Gorman, California. In an instant all on board Flight 23 were killed, and the wreckage of NC18645 lay burned and scattered on the rugged 80-degree granite slope where much of it remains to this day.

The primary cause of this accident was the high velocity crosswind encountered after leaving Palmdale. But, had the Newhall radio range been operational, the pilots could still have held their course so as to arrive over the Newhall station as planned. In the coming years a new system for aerial navigation would be perfected. It was called “VHF Omni-range”(VOR), and would replace the older N and A Range system in use during the 1930’s, 1940’s, and early 1950’s. The new VOR system was extremely accurate, and would allow an aircraft to remain within less than a mile of its intended course or position. Still later GPS (Satellite Navigation) would be used for aerial navigation, and would be even more accurate.

But in 1946 those methods were still in the mind of the science fiction writer. In the coming decades hundred of pounds of navigational equipment could replaced by a small half pound receiver that would fit in the palm of your hand. The accuracy and reliability of such devices was astounding. Until those new methods of navigation were perfected hundred, if not thousands, of aircraft accidents would still be attributed to faulty navigation on the part of the pilot. He would think that he was in one place, when in fact he was in another!

Link no longer active: http://www.donrjordan.com/waflight_23.html