|

|

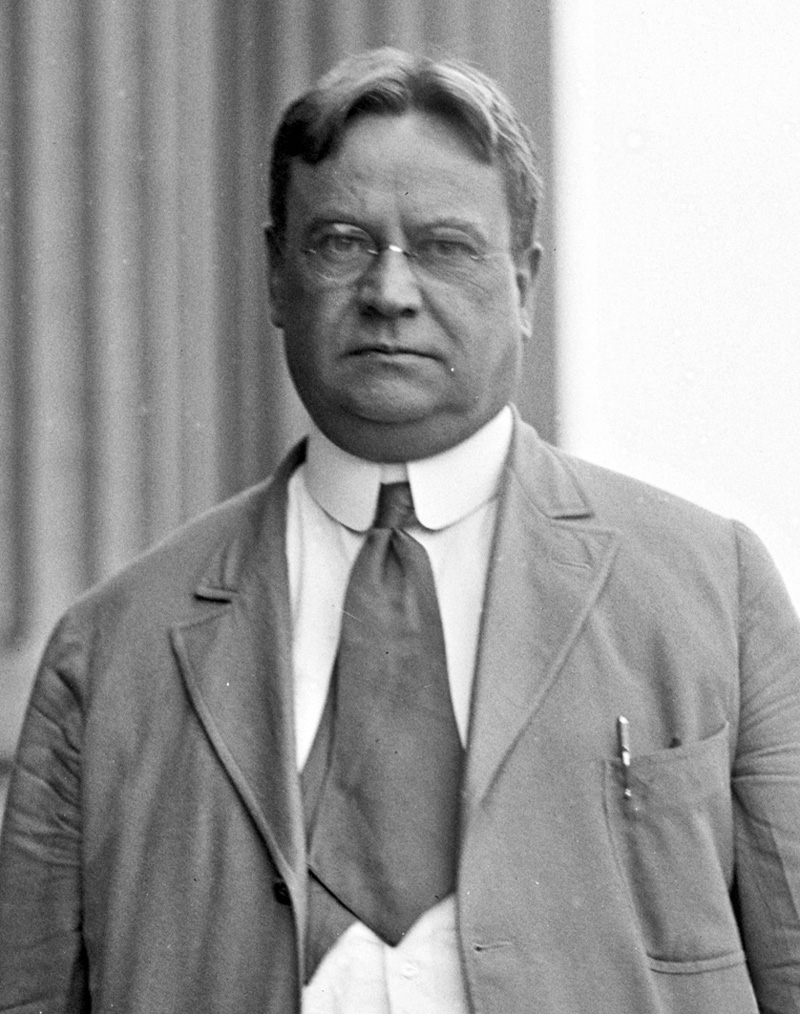

Report to Arizona Gov. George W.P. Hunt

on the St. Francis Dam Disaster

By Guy L. Jones

Member of Arizona Legislature | 1928.

|

Webmaster's note.

The Great State of Arizona gave it the old college try, but there was no stopping California's bull-headed maverick Republican governor-turned-U.S. Senator Hiram Johnson when he set his mind to something. The man who had given Californians the power to make and break legislation and to recall politicians at the ballot box teamed up in 1928 with his GOP Senate colleague from the Imperial Valley, Phil Swing, to push through the Swing-Johnson Act, authorizing the Boulder Dam on the Arizona-Nevada border. Los Angeles had its Owens River water; San Bernardino and San Diego would divert water from the Colorado River, by golly, and get the feds to pay for it. The first hearings on the act, H.R. 5773, were held Jan. 6, 1928. Arizona saw it as an illegal confiscation of its water and fought the bill, as did lawmakers from other parts of the country who considered it a waste of money that would benefit only California. Then on March 12-13, L.A.'s St. Francis Dam in Saugus failed. Arizona Gov. George W.P. Hunt on March 28 directed Arizona legislator Guy L. Jones to trek to L.A. to gather ammunition and quash rumors that the dam had been dynamited. Jones compiled a competent report (this report) on the whys and wherefores of the dam disaster and itemized the findings of L.A. District Attorney Asa Keyes' fact-finding panel. The upshot: "The dam was constructed without a sufficiently thorough examination and understanding of the foundation materials upon which the dam was constructed," and it "should not have been constructed at this location." Arizona commissioners used Jones' report in congressional hearings on the Swing-Johnson Act. "No other conclusion could be reached," the commissioners reported, "than that the utmost care must be exercised in ascertaining the safety of a damsite before selecting it for water storage. This Congress has thus far failed to do in the case of the Boulder Canyon damsite." Arizona's protestations seemed to fall on deaf ears, and some would say the St. Francis Dam Disaster was officially swept under the rug, forgotten, ignored, buried. The House of Representatives passed the Swing-Johnson Act May 25. The Senate passed an amended version Dec. 14, the House concurred Dec. 18, and lame-duck President Calvin Coolidge signed it into law on Dec. 21. Arizona sued the United States, California, and certain other states on grounds the legislation violated Arizona's sovereignty and water rights. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Arizona May 18, 1931. The dam went into construction that same year and was completed in 1936. It was officially renamed Hoover Dam in 1947. St. Francis Dam historian J. David Rogers adds: "St. Francis was built of mass concrete, as was Hoover a decade later, but that's about all the two structures had in common. Hoover was designed and constructed with so much more care, it's as though the two dams were built in different centuries. That said, there is no question that the failure of St. Francis resulted in far greater scrutiny of the Boulder Canyon Project than would otherwise have occurred, and we have Arizona to thank, in some measure, for that additional scrutiny." God Prosper the Commonwealth of Arizona San Francisquito Canyon Dam Disaster (California)

Report to His Excellency Copyright 1928

By Guy L. Jones

Geo W P Hunt

Executive Office Dear Mr. Jones: There has recently occurred in California a great disaster in the breaking of the St, Francis Dam. Many lives were lost and there has been a great deal of conjecture and many theories as to the cause advanced, — some even going so far as to say it was done by dynamite. I wish if possible you could go over there and make an investigation. You might be able to find out the real status of the case. We have built several dams in our state; so far we have never had any trouble, but the breaking of this dam has caused a great deal of uneasiness in our valleys. Our dams have most of them been built under government supervision and have stood the test of time; but there are other dams being contemplated. I feel we will have to, in the course of time, construct a great many dams in Arizona, and we never want to have a disaster if it can possible be avoided. If you can get any light on this subject, I will appreciate it very much.

Yours very sincerely,

Hon. Guy L. Jones, The facts presented in this report were gathered during an examination of the reservoir and dam after the disaster; by conversations on the ground with eminent geologists; by listening to testimony presented to juries and boards of inquiry; by examination of reports ordered made by competent authority; by conversations with survivors; and by an inspection of damaged property through the length of the Santa Clara Valley.

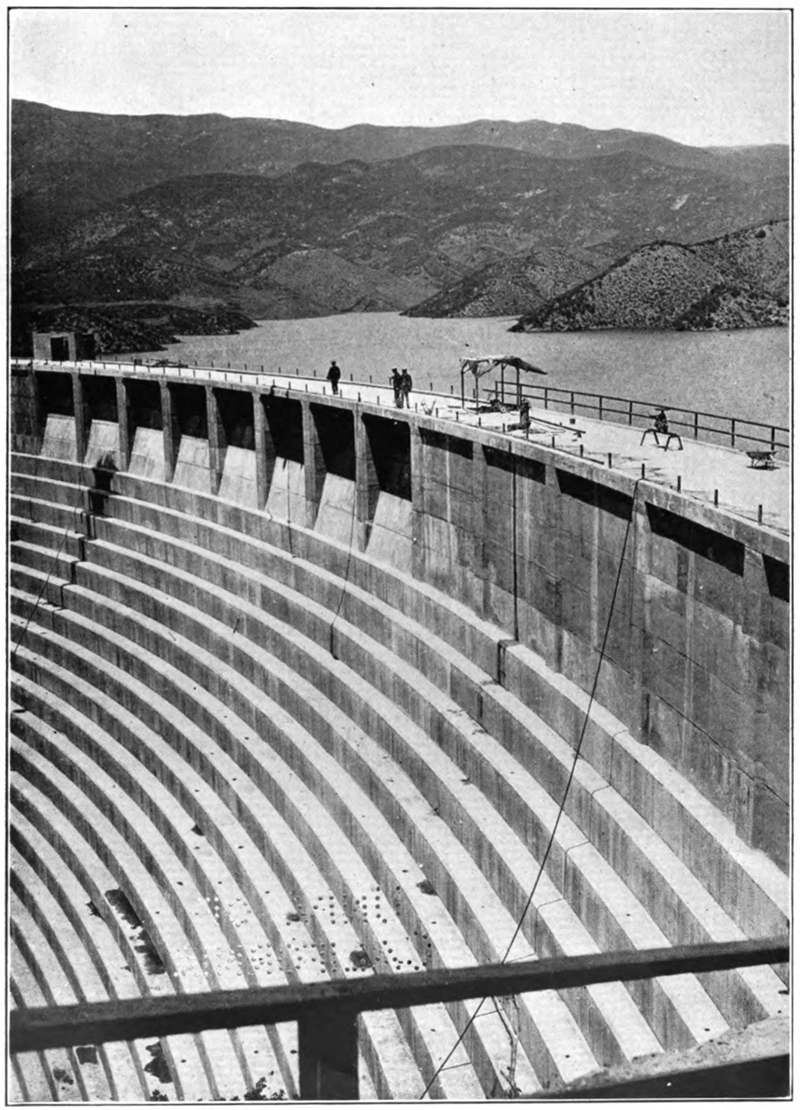

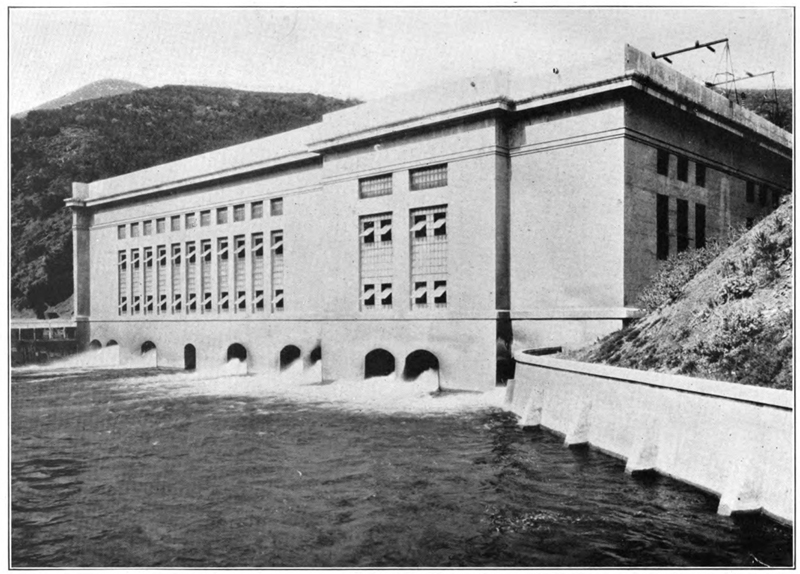

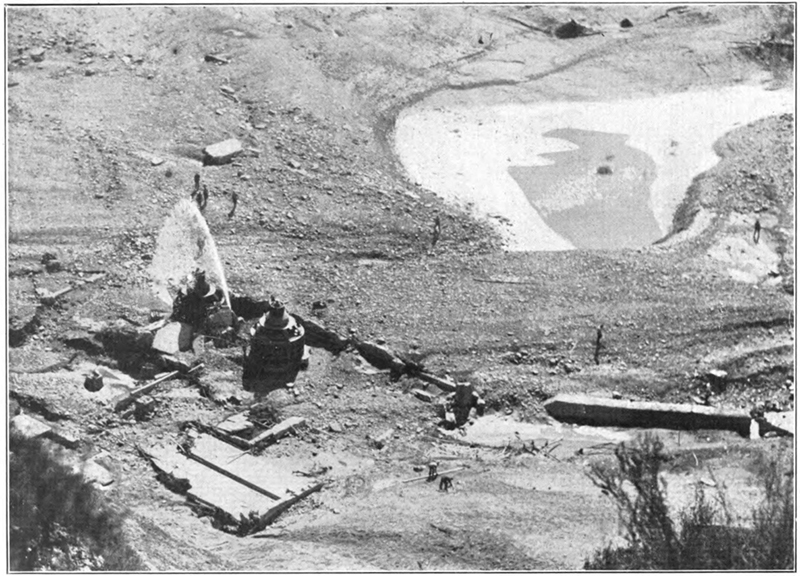

ON SHIFT IN THE POWER HOUSE Louis Burns, operator at Los Angeles Municipal Bureau of Power and Light, plant No. 2, in San Francisquito Canyon on the Owens Valley aqueduct, chuckled to himself as he hung up the telephone receiver, knowing that he too, would have his day off, come Wednesday of next week. That was a good dig he had just given Silvuy; a man could not help feeling a little sheepish when he came on shift after vacation, especially on the midnight shift. He walked over to the chart and made the entry and turned to sit down, when the lights flashed, a blue stream cracked across the front of the switchboard. Burns jumped for the switch to cut No. 2 out of series, dimly conscious of a tremendous roar above the hum of the two 15,000 K.W. turbines which supply power and light to the City of Los Angeles. He thought he heard his helper shout. The windows gave straight inward, then the walls, roof and floor seemed to meet each other in a gigantic convulsion and it was all over. A ninety-foot wall of water, carrying rocks, trees, detrital, swept over the top of the power house. The San Francisquito Dam had broken. "How did you know that it was 11:47, Mr. Silvuy?" asked E. J. Dennison, Deputy District Attorney, Los Angeles County, of the witness. "I was the operator on duty at power plant No. 1," was the answer. "I went on duty at 11:30 o'clock. I called up Burns, as usual, on coming on shift for the midnight check; we balanced loads." "But how did you know it was 11:47?" "The face of the clock was directly in front of me as I talked into the telephone. With my wife, I returned from my day off to Los Angeles and drove up the Canyoh from Saugus. We passed Newhall about 9:00 P.M. It was about 10:00 P.M. when we passed power plant No. 2, and then drove up the hill to the lake road, passing the dam at 10:15. We did not cross the dam but continued along the road that follows around the lake to power plant No. 1. I went on shift at 11:30 and at 11:47 was talking with Burns." Of the thirteen men and their families employed in the operation of the power plant No. 2 who lived in the neat little settlement up a draw nearby, the school teacher and the ranchers and their families from the dam down to Carey's ranch, five miles north of Saugus, there is one single survivor. He was a light sleeper; was continually predicting the dam's failure; was laughed at for his pains. He said he heard his dog bark; heard a noise; jumped out of bed into his shoes, with a yell of warning, and climbed with all his might up the canyon side. He was just high enough to turn and see the black calamity pass beneath him. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT The San Francisquito reservoir was first projected in 1922. Two ranches in private ownership in the canyon comprised most of the area, the balance of which was unoccupied public land acquired by the city of Los Angeles upon application to the Federal Government. The Canyon lies forty-five miles north of Los Angeles, among the California hills, to the left of the road to Mojave, and about sixty-five miles from the sea, near Oxnard. The drainage area of the Canyon's watershed is 37 square miles and the surface area of the reservoir, when filled, was three and a half miles long by varying width. The aqueduct from the Owens Valley came out through the mountain above the site of the reservoir and was passed down through an iron conduit to power house No. 1 near head of Canyon where it again entered the mountain above the level of the reservoir, and through a tunnel of five miles, passed the east side of the reservoir to a point one and a half miles below the site chosen for the dam. Here it again came out of the rocky ridge and through two large iron tubes passed directly down the side of the ridge at an acute angle into the turbine races of power house No. 2 in the bottom of the San Francisquito Canyon. The penstock under power house No. 2 directed the water again into a tunnel, coming out on the other side of the ridge, at an elevation, as the Saugus siphon. From there, it flows through tunnels and exposed pipe to the San Fernando power plant and reservoir, at the head of the San Fernando Valley, above Van Nuys and Lankershim. The reservoir was designed to contain thirty-eight thousand acre feet of water and at the time of the failure of the dam was nearly full. This reservoir differs in relation to the Owens Valley from our subsidiary reservoirs in the Salt River System, at Mormon Flat and Horse Mesa; this reservoir was not in series with the power generating units. It was filled by diverting at power house No. 1 a portion of the water from Owens Valley after that water had passed through the turbine at power plant No. 1. The other part of the water then continued directly through the aqueduct and through the lower power stations, No. 2 and San Fernando. The portion for the San Francisquito reservoir went into this lake. It would not be impossible, however, to have constructed works to utilize this water when released for the aqueduct again. The reservoir was merely an auxiliary water storage device and in an emergency contained sufficient water to supply the needs of the city of Los Angeles for three months. The topography reveals a high range with very steep sides on the east of the reservoir with low, irregular hills on the west. It made a beautiful clear lake. The dam was of the gravity type, arched upstream and keyed into the east bank, on the west running up the slope of the end of the hill, augmented by a low wall across the top of the first hill and a saddle, in order to increase the surface area of the reservoir. Farther west, the ground rose several hundred feet above the high water contour. The dam was 205 ft. high, 176 ft. wide at the bottom, 1225 ft. length at crest, lengthened 200 feet by a retaining wall. From upstream face to downstream toe, the dam was 165 feet thick, at bed rock, with steps up the downstream face with five-foot risers lengthening in tread from top to bottom. The elevation of stream bed was 1630 ft. above sea level. 175,000 yds. of concrete was used, with 1-12/100 barrels cement to the cubic yard. The aggregate was made of stream bed gravel and sand, containing coarse rock run through a six-inch grizzly. The surfaces were floated and rendered impervious to water and the average crushing strength of five samples of the broken concrete was 1758 pounds per square inch. No reinforcing bars were used, nor did good engineering practice demand their employment in a concrete, gravity-type dam of this size. Five thirty-inch diameter drainage pipes were placed at the foot of the dam, controlled by gates from above. The work was begun in March, 1924, and finished in June, 1926, and the reservoir was being filled for the first time. It contained 36,000 acre feet when the dam failed.

GEOLOGY The east wall of the Canyon into which the dam was anchored consists of quartz mica schist with a strike north 55 degrees west or diagonally across the base of the dam. The schist crosses the stream bed and a main fault with a change of dip, and continues up the west bank 65 ft. above the stream bed at the dam site, to the contact with the sespe conglomerate. The anchor-way face was at right angles to the thrust of the dam in place. The west bank is conglomerate in contact with a metamorphosed sandstone and dark basic shale. Two clearly defined faults existed in the west bank, the largest of which was exactly where the west bank began to rise. The cleavage planes under the west side of the dam between the conglomerate, the sandstone, and the mica schist, are very mixed up. Igneous rock thrust into the formations confuses the situation. It is a typical case of the Franciscan sespe familiar to California geologists. Over this was laid the red clay of the California hills to a depth of four feet. The foundation of the dam was prepared by using a hydraulic giant and washing down all loose dirt to a depth of five feet exposing bed rock, and then with drill and pick clearing the surface of all loose rock until a firm foundation was secured. "Did you employ any geologists to study the formation under the site chosen for the dam?" Mr. Mulholland was asked during the course of the inquiry. "No," he replied. "Are you a geologist yourself?" "Well, I don't claim to be, but a man learns something about rock who has drilled fifty-three miles of tunnels through these hills. I have built nineteen dams in my time; I have been consulted in the building of nineteen more. Hind sight is always better than foresight. We thought we had the bed rock when we built this dam. We have never had a failure yet and we have never heard the slightest criticism of the site chosen for this dam. There isn't a square mile of Southern California where there are not prominent faults." As the dam began filling with water, the altered sandstone and the conglomerate on the west bank became saturated with water and the inthrusts of decomposed mica schists began to soften. Where the water percolated into the cleavage planes as the surface of the reservoir rose, and greater pressure continued being exerted through the hydrostatic head, these forces met the bottom of the dam, and created stresses for which the dam was not designed. The conglomerate, which when dry, was hard, softened. In places it was like slick mud. A piece of the altered sandstone and quartz mica schist, thoroughly saturated, broke in the hand.

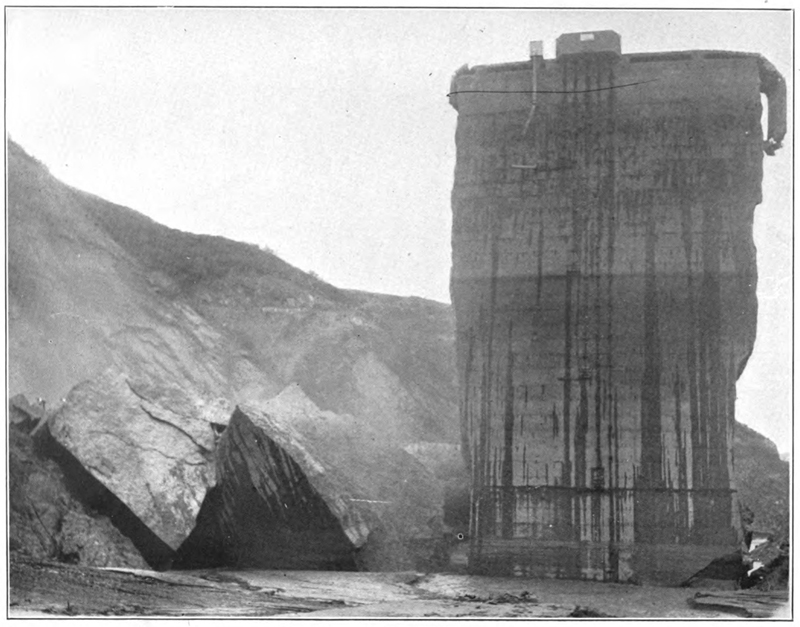

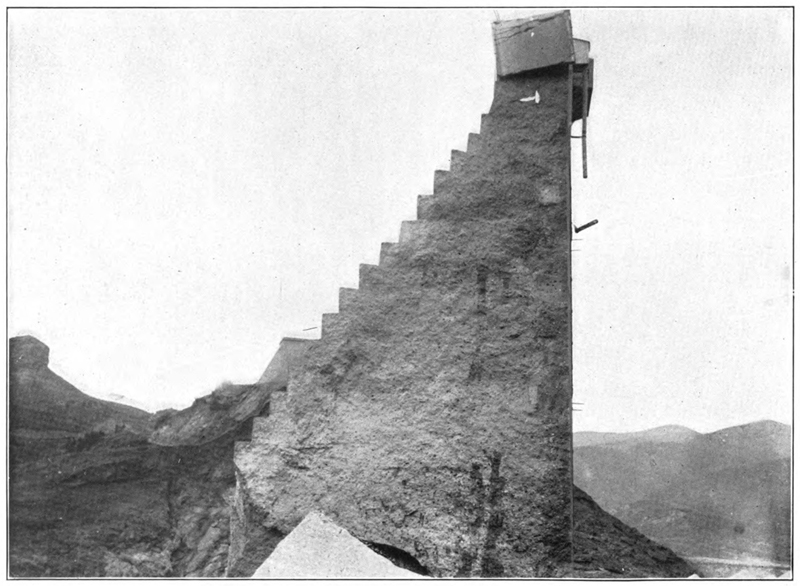

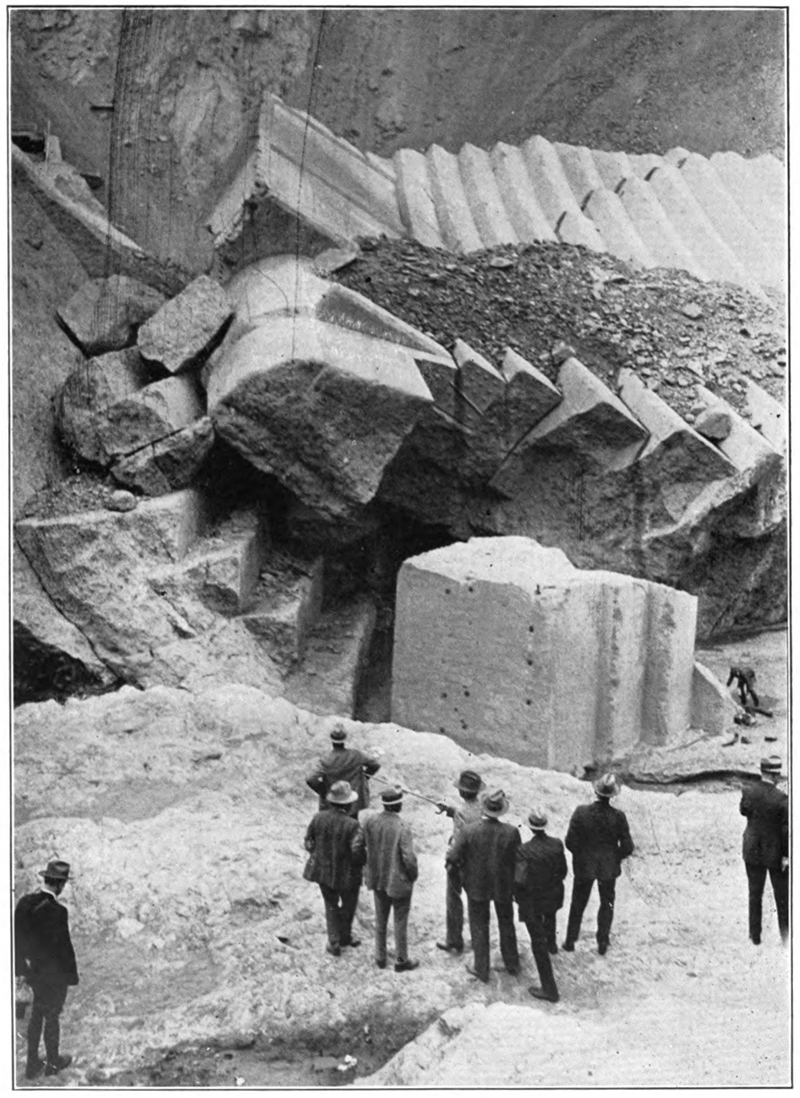

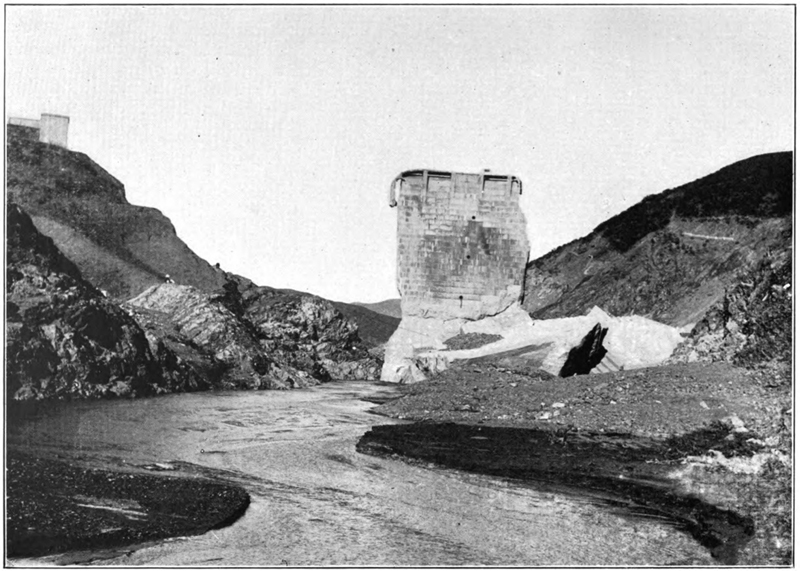

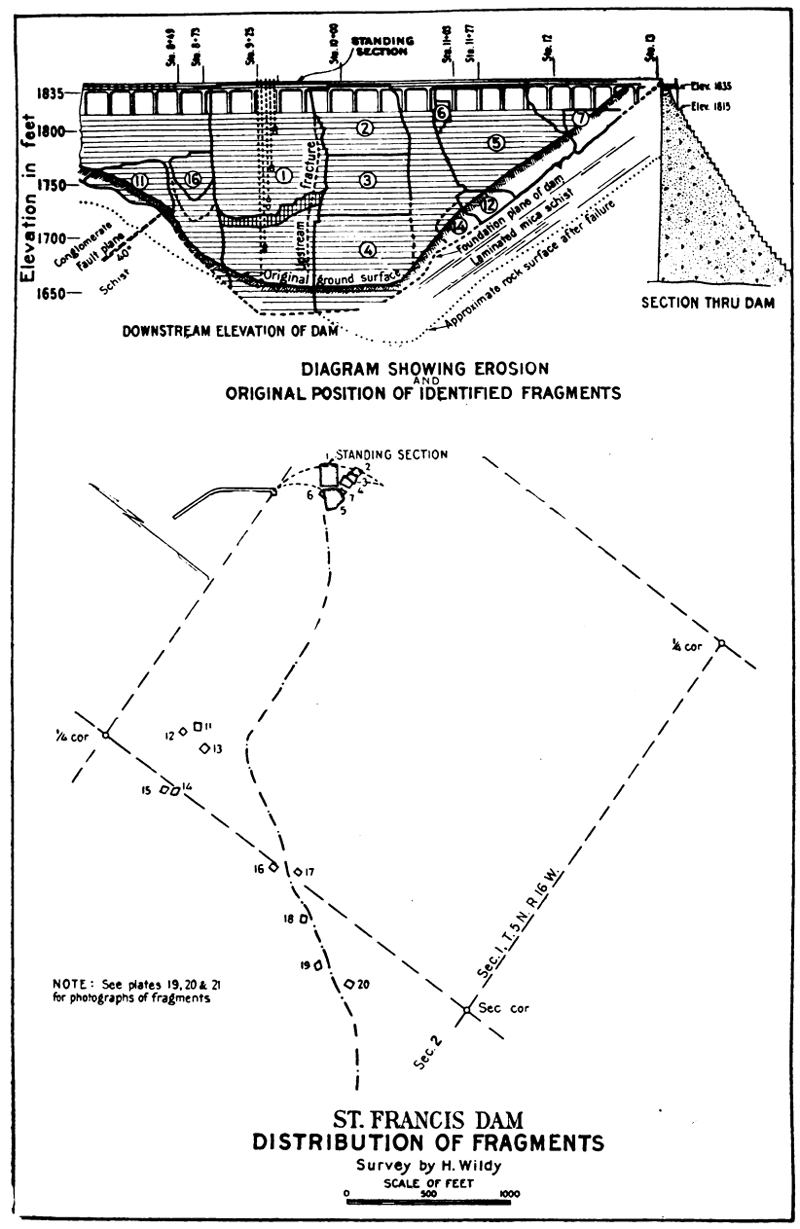

FAILURE In the center of the stream bed stands a section of the dam 205 ft. high, 75 ft. wide at the bottom, 86 ft. wide at the top. The present position of its top is 7/10 of a foot down stream, and the piece has been revolved upon its axis 8/10 of an inch at the corner of its down stream toe. The cleavage upon both sides is sharp. To the east of it are piled several sections, one of which has fallen a few feet upstream from the face of the standing section. Nine pieces from the west side are observable at intervals for one-half mile down stream. The largest of these pieces — 85 feet long by 50 feet thick by 65 feet wide — as large as a six-room house — weight 10,000 tons — lies 1500 feet down stream; at 2500 feet, a piece nearly half this size. These are partly buried in the gravel and detrital with which the stream bed is filled. The back portion of the standing section has been sheered [sic] vertically, suggesting that the standing section, by the force of the collapse, was rocked backward on its down stream toe by the force of the crash; this suspicion is further strengthened by the presence under its upstream toe of a water-soaked wooden ladder which might have been sucked under, while the section tottered down stream, and1 was bitten and crushed to the thickness of paper as the standing section rocked forward again. Clinging to the concrete on the under side of broken bed rock sections of the dam, are areas of the mica schist, proving that the cleavage was through the rock and that the bond between the concrete and the rock was stronger than the rock itself.

A great deal of discussion among the geologists and engineers has followed the identification of the great segments of the dam as they lie half buried in the detrital down the stream. From their position and size, opposite theories are supported from the same set of facts. More than a full day's discussion followed an analysis of the recording instrument's record of the float gauge's movements for the 23½ hours preceding the collapse of the dam. Microscopic and microphotographic studies have been made of this record by eminent engineers, conclusions being reached by one group that the west side of the dam broke first; and by the other group that the east side broke first. During the last three and a half hours, the water level at the face of the dam is shown to have fallen seven-thirty seconds of an inch, and the conclusion is drawn that 74 second feet of water was disappearing under the dam foundations, some 9,000,000 cu. ft.; while the inferential testimony is that the men who would be watching for it down stream, observed that no water was escaping. By this is meant that the caretaker, whose duty it was to be on the lookout for leaks, went home after inspection and went to bed in the camp down stream, below the dam, at 11:30, and that the operator at power house No. 2, who talked with Mr. Silvuy at 11:47, and who, fifteen minutes before, had walked across the bridge over the sluiceway as he was going on shift, had noticed no unusual change in the water in the sluiceway such as 74 sect, feet would cause. At least, he failed to mention it when reporting conditions and checking loads with the operator at the power house No. 1. Of course, every person who was in actual position to observe, was lost in the catastrophe.

No less than seven inquiries into the cause of the dam's failure have been undertaken by official bodies. District Attorney's office of Los Angeles County, the State Railroad Commission, the Governor of California, through a board of five engineers, the coroner's jury of Ventura County, the City Council of Los Angeles, and the Mayor's Commission of Santa Paula, are six of them. The members of the Fact Finding Commission, appointed to investigate the failure of the dam for District Attorney Asa Keyes' office of Los Angeles County, were: Edward L. Mayberry, Walter G. Clark, Col. Charles T. Leeds, engineers; Prof. Allen T. Sedgwick, Louis Z. Johnson, geologists. The engineers appointed by the City Council of the City of Los Angeles, were: Dr. Elwood Mead, former director of the Reclamation Service; Louis C. Hill, consulting engineer, and former Reclamation Service supervising engineer, who built the Roosevelt Dam; Maj. Gen. Lansing H. Beach, U.S. A[rmy] (retired), former Chief, Corps of Engineers. The Board of Supervisors of Los Angeles County secured their report from the consulting engineers permanently employed by the Board. They are: J.B. Lippincott, former engineer of the Reclamation Service, who resigned to come to Southern California and start the building of the Los Angeles aqueduct, 20 years ago; D.C. Henny; and J.W. Reagan, former chief engineer of the Los Angeles County Flood Control District. Gov. C. C. Young appointed for the State's investigating body the following well-known authorities from a list proposed to him by American Society of Civil Engineers: A.J. Wiley, Chairman, Consulting engr., Boise, Idaho. Geo. D. Louderback, Prof, of Geology, University of Calif., Berkeley, Calif. F.L. Ransome, Prof, of Economic Geology, Calif. Institute of Technology, Pasadena, Calif. F.E. Bonner, Dist. Engr., U. S. Forest Service, and Calif. Representative on Federal Power Commission, San Francisco, Calif. H.T. Cory, Consulting Engineer, Los Angeles, Calif. F.H. Fowler, Consulting Engineer, San Francisco, Calif.

CAUSES ADVANCED The most eminent engineers and geologists have been employed. The reports and testimony are voluminous, making some 2,000 pages of printed record of fact, conclusion, recommendation. Four theories are advanced for the cause of the dam's failure. 1. Seismographic disturbance. 2. Dynamite. 3. Percolation and saturation under dam through seepage. 4. Natural surface landslide. 1. SEISMOGRAPHIC DISTURBANCE. A very careful check and re-survey by C.F. Homberg, engineer of the Bureau of Power and Light, who made the original triangulation, shows the dislocation of one of the points in that survey on the top of the west hill. This survey, checked and rechecked, shows that the point, which was an iron pipe, in the cement retaining wall at the west end of the parapet, placed at a distance of 1200 feet from the center of the dam, has moved 7/10 of an inch eastward, or toward the opposite canyon wall. A closed survey and check by two level parties from one U.S.G.S. bench mark to another, shows that this point has risen 3¼ inches. From this, it is concluded that a seismographic disturbance pushed the west hill and the west side of the dam upward, and, pressing across the Canyon, crushed the dam in its vise-like grip, shattering it into the dozen immense fragments which are counted down stream. This theory is strengthened by the spauling off of the section of steps lying against the down stream face of the standing section, in the center of the dam site. Against this, however, is the evidence of the seismograph instrument at Santa Barbara, only 80 miles distant; the instrument at Stanford University and the famous instrument at Georgetown University at Washington, D.C., where the evidence is all negative; no seismographic disturbance was recorded.

2. DYNAMITE. A rope and a piece of paper, with diagram and directions, formed the basis of this suspicion. A newspaper story describing a piece of concrete being broken between fingers by Coroner Nance, and an explosive expert of El Paso, made a chain. Coroner Nance, who did not see the story, stated later it was stone, not concrete, he was breaking. "Mr. Mulholland never made any concrete that will break in a man's finger," testified Mr. Z. Cushing, who, for four years, experted explosives during the building of the aqueduct for both the Bureau and the E.I. Dupont De Nemours Powder Company. "That's the result of an explo- sive." The piece of concrete discovered farthest down stream is identified as a piece from the base of the dam eighty feet down from the top eastern corner at a depth of fifty feet under water. Mr. Frank Rieber, testifying before the District Attorney's inquiry as a geologist and physicist, specializing in the application of the laws of physics to the earth's crust, identified this piece, and from its position drew the conclusion that it was the first piece to go. From the position on the upstream face and its shape, showing that it reached through the entire structure, some powerful external force must have expelled it. The hanging rope, found subsequently, led to an inquiry of the size of the charge needed to start the structure to fail. Mr. Cushing thought that 50 pounds of low velocity gelatin for a minimum, and certainly not more than 250 for a maximum, would have been needed. "Would that not have made a terrific noise, which would have been heard?" asked a member of the jury. "At a depth of 50 feet under water, it would scarcely have been heard at all," he replied. "Every fish which we found, either in pools above the dam or below the dam, was dead when we made our examination," testified Professor Shark of the State Fish Hatcheries' Department. "We were called a week after the failure of the dam by the Bureau of Power and Light." "Do you know from your own experience that a charge of dynamite exploded in water will kill fish?" he was asked. "I do." "Will it?" "Yes." "That is all," finished the attorney for the Bureau. Professor Bailey Willis, world famous geologist and seismographic expert of Stanford University, was pointing out to the writer as they sat together on the fallen debris, a crack in the structure. "Did you hear that dynamite theory?" he asked. "You see this? Oakum caulking in the crack. That's the piece of rope they found." 3. PERCOLATION AND SATURATION of rock under dam through seepage. The entire hillside on the west bank became softened through the percolation of the water into the structure of the altered sandstone and into the structure of the conglomerate. So wide a crack as one-quarter inch filled with recently deposited gypsum or quartz mica sediment can be easily identified in the bare surface at a depth of 20 feet below the foundation upon which the concrete of the west wing was laid. From the faulting between the sandstone and the mica schist at the west edge of the stream bed to the bottom of the mud or red clay with which the hill was overlaid, the entire west wing of the dam permitted the penetration of water thoroughly through the hill. Streams of small size were known to exist on the back side of the dam. These discharged, however, clear water on the afternoon before the dam's failure. One of these was discharging a stream "as large as a man's leg." Mr. Mulholland and Mr. Van Normand [sic], assistant chief engineer, both examined this at noon of the day before. It was clear and they were satisfied that no new or dangerous alteration was taking place under the west wing of the dam. The theory upon which the "Fact Finding Board," consisting of the well-known geologists, E.L. Mayberry, Allen E. Sedgewick and Louis Z. Johnson, the engineers W.S. Clark and Charles T. Leeds, proceeded was that the softest of this west hillside where the conglomerate under the action of water had become little better than a soft mud strata, sustaining its aggregate of desert pebbles, permitted the passage of a very small and rapidly increasing volume of water as a consequence of the pressure of the 80-foot head in the reservoir. This rapidly increasing flow removed the foundation material of the west wing of the dam; a tremendous gouge left the wing in suspense. The weight of the concrete in cantilever shape then collapsed the wing, the water drove it down the hillside and down the canyon, its bending movement shifting the standing section down stream and breaking it off from the east wing. The east wing then collapsed through three major vertical cracks. A part of the force of the water by this time lost down stream, the large segments fell into the river bed against the base of the standing section, where they now lie. The force of the escaping water under the west side struck diagonally across the channel against the base of the east wall, undercutting the schist and producing a very large slide behind what had been the abutment of the east wing of the dam. 4. NATURAL SURFACE LANDSLIDE. Natural slides had been occurring under the water in the reservoir in the mica schist along the east wall up to a quarter of a mile above the dam. They are easily discernible in the bed of the now dry reservoir. Both the strike and dip of the mica schist on the east side favored this action. As the water softened the rock toward the bottom of the ridge, these small slides were occurring during the last year, in all probability. The theory is now advanced that the cause of failure of the dam was that the lip on the down stream edge of the abutment, where the east wing of the dam impinged upon the schist cliff towering over the east side of the canyon, just slid down, giving the east wing the opportunity to slip off the shoulder against which it lay. It then, yielding to the pressure from the west, tilted the standing section to the east, broke it off from the west wing and caused the subsequent collapse of the west wing. The slide, or remaining evidence of the slide, are plain to be seen. The objection to this theory is that the great pieces into which the east wing broke, now lie at the foot of the standing section, partly in front thereof; while the equally large pieces of the west side are found from a quarter to a half mile down stream. ECONOMIC LOSS The cost of building the dam was $1,250,000. The entire valuation of the aqueduct system is approximately $125,000,000, making the dam and reservoir equal one per cent of total value of the system. The water stored was one-fourth of the year's use in Los Angeles. Six per cent interest on the valuation would make the value of water and power to Los Angeles, at $7,500,000 a year. A quarter of a year's storage, which the reservoir contained at time of the collapse would have a value of $1,875,000. Its electric power revenue through one subsequent use, might be a half a million dollars more, so that $3,625,000 might be a very conservative estimate of the economic loss due to the dam's failure. Interruption of water service, there was none. The rebuilding of the power plant No. 2, and the repair of a short portion of the aqueduct may amount to $200,000; to this may be added the loss of revenue from power plant No. 2 until the plant is rebuilt. Property loss and damage, and personal injury and loss of life, are placed at the stupendous total of $12,000,000 and 451 lives. DESTRUCTION IN THE SANTA CLARA VALLEY From the record of the gauge recording device on the dam and the records of the interruptions of service in the power houses above and below, the dam crashed at 11:57 P.M., March 12th, and swept away the power plant a mile and a half below at 12:02 A.M., five minutes later. The rate of progress of the wall of water down the canyon was 26 feet per second, or 18 miles per hour. It reached the sea, 66 miles distant, five and three-quarters hours later. Down stream from the power house, it reached: The Carey Ranch 7 — miles distant at 12:30 A.M. Saugus — 9 miles distant at 1:05 A.M. Castiac [sic] Junction — 5 miles distant at 1:28 A.M. Piru — 12 miles distant at 2:18 A.M. Fillmore — 8 miles distant at 2:55 A.M. Santa Paula — 10 miles distant at 3:45 A.M. Saticoy — 9 miles distant at 4:30 P.M. The Sea — 6 miles distant at 5:45 A.M. At Santa Paula, the stream was twenty-three feet deep; at Saticoy twelve feet. As the river widened still farther, it reached the sea relatively slowly at a depth of about eighteen inches. The destruction at Newhall was to the land of the

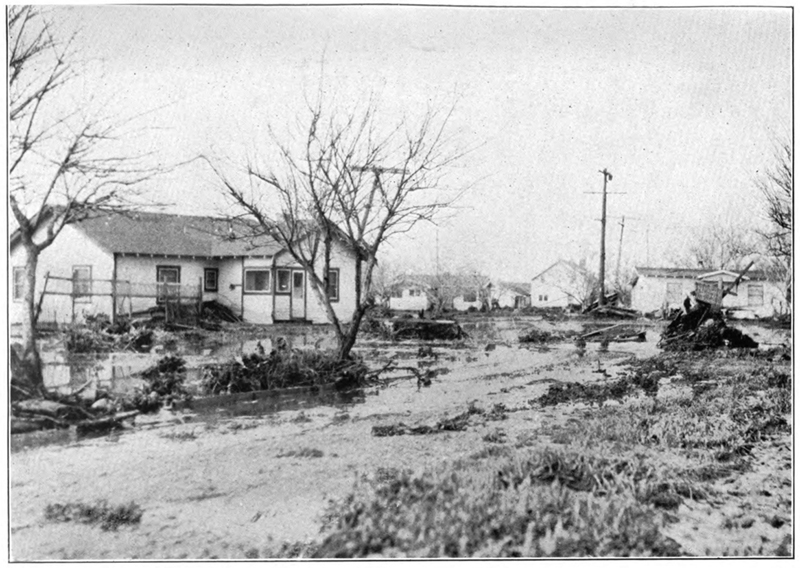

Newhall Ranch, which was overflowed, covered with sand,

through which arroyos were cut and edges of banks broken

off and washed away.

While the destruction of life in the canyon was nearly 100% of all people living between the dam and the Carey Ranch, this total did not equal the number of lives lost farther down and among the men in the Southern California Edison Company's construction camp, where the Newhall Creek joins the Santa Clara River between Saugus and Castiac [sic]. Ninety-one men lost their lives out of a total of 174 names on the pay roll in that division. Asleep on their camp cots and without warning, finding their tents falling about them and the water rushing across the floor where the camp was located on the edge of the steep arroyo, they rushed outside in the dark to find themselves staggering and overwhelmed and swept off into the deep pool which an eddy was filling at the edge of their camp. One survivor said that he owed his life to a tent pole which, in the darkness and confusion, he had seized. All of his tent mates were lost. The destruction to highways, bridges and railway was greatest at this point. Steel spans were carried hundreds of feet down stream; pile bridging was rooted out; concrete retaining walls and piers toppled over. The State highway running north to Bakersfield was 18 inches to 4 feet deep with sand, uprooted trees and brush, a distance of three and a half miles. Ten miles of the Southern Pacific branch line between Castiac Junction and Piru, as well as eight miles of the State highway, were washed away or covered several feet deep with sand and driftwood. A gas station and two houses at the former point disappeared entirely. At the last place down stream where loss of life was recorded, Santa Paula, eighteen people in the lower section of town lost their lives. The river bottom here was a mile wide. In Los Angeles County, the loss of life was largest and the property damage, as calculated in the loss of the dam and the water, was probably the greatest. But in Ventura County the number of people affected, the number of properties injured and destroyed, and the general interruption to business was felt worse. For the purpose of arriving at an estimate of the damage and for fixing a basis of settlement, which the city of Los Angeles quickly offered to do, twenty-three agricultural extension service workers were detailed by the University and by Governor Young for a survey, under the direction of the Horticultural Commission of Ventura County. They find in their report that 190 properties have been damaged in varying degrees and that the total acres of ranch lands injured is 10,658. These are divided as follows:

Oranges — 915 acres In varying degrees of injury, 75 houses in the lower portion of Santa Paula now stand deserted. Some have been lifted and turned on their lots, some have been carried a block or more away from their foundations. According to Mr. C. C. Teague, a prominent lemon grower of Santa Paula, the families in the disaster, aided by the Red Cross, were as follows:

One of the intangible considerations which will also affect the property damage situation is called "river hazard." By this is meant changes in the river channel, due to the flood and to the deposition of sand in the river bed. At some places water is now running over land that was formerly farmed, and some places there is no water where there was water before. Water for irrigation in the Santa Clara Valley is developed by surface seepage and pumping from the gravel beds. Changes will be found to have been made in the source or location of water which maintains the orange orchards from the underground storage in the gravel beds. No discussion of damage will be complete until this serious item of source of water supply has been thoroughly studied. Likewise, in Ventura County, under the direction of Coroner Reardon, Deputy Attorney Hollingsworth presented his evidence before a jury consisting of L.H. Dunning, Oliver L. Reardon, F.T. Parrott, W.G. Moore, J. Lon Hall, Earl Foolweather, Willard Smith, L.D. Eaton, J.H. Shrive, George W. Caldwell, all men of earnest determination to get to the root of the matter. There was heat in the discussion and some sections of public opinion are not satisfied that the builders of the dam should go unpunished. Dr. W.D. Mott, former State Senator from the Santa Clara Valley district, in a heated reply to Governor Young, upon the occasion of his appointment of a commission of inquiry, stated: "The responsibility is that of a selfish city which took the water belonging to us." The water referred to was the normal flow in the San Francisquito Canyon and the flood waters which, in rain storms, were collected on that watershed. As a fact, however, no measurements of either the normal flow nor the flood waters had ever been made so that when a temporary agreement was reached a year ago by which the Bureau of Power and Light was to release a head of 300 miner's inches all the time, public opinion in Santa Clara Valley was satisfied. CONCLUSIONS No one can doubt the high character, of the men employed on the Fact-Finding Commission, nor doubt the interest, intelligence and particular adaptability of the jury to listen to all the testimony about the failure of the St. Francis Dam, which was impanelled by Los Angeles County Coroner, Frank Nance. They are engineers, contractors, geologists, business men, whose services in professional employment are measured by a rate of $100 a day; they are giving their services for nothing. They are: Oliver Bowen, Engr.-Contr., 1144 So. Grand. C.D. Walz, Mech. Engr., 1144 So. Grand. Harry G. Holabird, Appraiser, 621 So. Hope. Capt. B. Noice, Struct. Engr., 1325 Washington BIdg. I.C. Harris, Contr., 606 So. Hill. Sterling C. Lines, Engr. Finance, 621 So. Hope. W.H. Eaton, Jr., Build. Contr., 1317½ So. Van Ness. Z.N. Nelson, Engr. Bldg. Const., Scofield Twaits Eng. Corp., 1100 Pacific Finance Bldg. Ralph Ware, Insurance, 552 Roosevelt Bldg. Conflicting statements were published. Wide circulation was given the statement of Stanley Dunham, construction engineer and superintendent when the dam was built, who said that only an external force could have crashed the dam. Only thirty-six gallons of seepage in twenty-four hours, a negligible amount, had been escaping, the smallest quantity ever checked by him. The dam was dry. The foundations were rock on one side and conglomerate on the other, checked by a diamond drill. Test holes were also filled with water. The first report of the cause of the failure of the dam attributed to Mr. Mulholland and his Chief Assistant Engineer, Mr. Van Norman, was quoted as the giving away of the mountain on the west side of the canyon. This was not part of the dam itself, but was a 1500-foot dike, or secondary dam, which acted as an abutment or anchorage for the main central portion or arch which still stands. As the west side dike gave way, water poured through into the canyon. Mr. Van Norman said: "The rush of the water weakened the dam, and the east mountain side next crumpled, followed by a break on the east mountain anchorage. Water poured through this opening. The two breaks caused rivers of water to pour through the canyon. The reservoir was then emptied of its 36,000 acre feet within a few hours." It is small wonder that the public mind continues confused about the causes of the disaster when it is fed with statements of this kind.

While the rules of evidence were used as a guide in admitting testimony before the boards studying the causes of failure of the dam, the purpose of the inquirers was to get at the facts and to hear the opinions of every qualified witness. An observer present during the hearings felt that no sooner was one reasonable point established than testimony was introduced for the purpose of discrediting the fact brought forward. This was done by the attorneys for the Bureau of Power and Light. The consequence was that while the Bureau brought forward no theory or explanation of its own, it constantly maneuvered to befuddle the jury or investigating board, which, of course, was reflected in the newspapers. Undoubtedly, there will be no finding of criminal responsibility and no criminal prosecution; at the same time, the facts brought out, and the verdict of the Coroner's jury will be an important issue in the next political campaign. The dam was the last word in engineering design, built and designed under the personal direction of William Mulholland, and constructed by city engineers. It was a gravity type concrete, arched upstream, similar to the Elephant Butte Dam in New Mexico, built by the U.S. Reclamation Service. It is fair to quote here the conclusions reached by District Attorney Asa Keyes' "Fact Finding Commission," the names of whose members are given on page 13. This conclusion is as follows: 1. The failure of the dam was due to defective foundation material, some of which, while reasonably hard when dry, became soft and yielding when saturated with water. 2. The defective foundation material referred to herein as conglomerate became softened by absorption and percolation of water from the reservoir and was by hydro-static pressure pushed out from under the dam structure, permitting a current of water at high velocity to pass under this sector of the dam. This current, by eroding the soft foundation material, quickly extended the opening under this portion of the structure to such an extent that a part of the westerly sector of the dam collapsed through lack of support. 3. Following failure in the westerly sector, the escaping water swirled across the downstream toe of the dam to the easterly side of the canyon, cutting away the easterly wall of the canyon below the easterly abutment, causing a slide which broke the already weakened bond between the easterly sector and the side wall of the canyon, allowing the easterly sector of the dam to collapse. 4. A portion of the easterly sector of the dam fell and now lies upstream from the original face of this sector, indicating that this portion failed after the water level had dropped enough to materially relieve the pressure from the upstream face. 5. The top of the central sector of the dam now standing is approximately 7/10ths of a foot downstream from its original position. The present angle of the upstream face indicates that in addition to moving downstream, this sector of the dam has rotated a slight degree, carrying the westward side to the southeast. 6. Examination of the foundation material supporting the sector of the dam now standing, shows a fracture in the schist upon which this sector rests, indicating that the break which permitted the downstream movement, occurred in the foundation materials and not in the concrete of which the dam was constructed. 7. The condition of the foundation under the central sector and the foundation materials now attached to blocks of concrete carried downstream, indicate that the bond between the concrete and the foundation was stronger than the cohesion of the cleavage planes of the foundation materials. 8. The gauge indicates the collapse of the dam occurred between 11:30 and 11:50 P.M. The movement of the gauge after 11:30 is so rapid that it cannot be accepted as an indication of the water level in the lake, but merely as an indication of the water level at the face of the dam. 9. It is the conclusion of this Commission that the dam was constructed without a sufficiently thorough examination and understanding of the foundation materials upon which the dam was constructed. 10. It is the conclusion of this Commission that failure of the dam was due to the incompetent geological formations upon which the dam was constructed. 11. It is the conclusion of this Commission that the dam as designed should not have been constructed at this location. 12. It is the conclusion of this Commission that due to local conditions it is not economically feasible to erect a safe dam at this location. RECOMMENDATIONS Your Commission feels that this investigation would be incomplete without urging strong measures to prevent a repetition of such a disaster. Your Commission, therefore, recommends: 1st. That all dams within the Los Angeles District be examined and reported on by a competent Board of Engineers and Geologists. 2nd. That any dam or dams found to be defective in any way be corrected in accord with the recommendations of the Board. 3rd. That the State Legislature be petitioned to enact legislation which will require a State permit for the construction of any dam for the impounding of water within the State of California. 4th. That the Governor be empowered to appoint a Board, composed of properly qualified Engineers and Geologists, to in future pass upon the design, foundation, conditions and construction of all dams constructed within the State of California, and that no Permit for the construction of any dam be issued unless the design, foundation and conditions be approved by this Board. 5th. That this Board be required to employ a competent superintendent or superintendents of construction, to supervise the work at all time during the construction, to see that the construction proceedings are in accordance with the design and conditions approved by the Board. 6th. That the Board appointed by the Governor receive compensation only for the specific project on which it is called to pass judgment. 7th. That an applicant for a Permit to construct a dam be called upon to pay into the State Treasury a sum sufficient to compensate the members of the Board, and superintendent or superintendents of construction, for their services and expenses incurred in connection therewith. 8th. That the Board and superintendent or superintendents of construction draw their compensation from the State Treasury. 9th. That Federal, State, County or City employes, drawing regular salaries from these divisions, shall not be eligible to appointment on this Board.

GOV. G. W. P. HUNT, CHAIRMAN

Colorado River Commission of Arizona July 15, 1928.

Hon. Guy L. Jones, Dear Mr. Jones: Your report on the failure of the San Francisquito Canyon Dam (California), which occurred on the night of March 11-12 [sic], 1928, was forwarded by Governor Hunt, together with the nineteen photographs and seven engineering drawings accompanying it, to the Commission, for use in the hearings which we secured before members of the Senate and House while we were endeavoring to defeat the passage of the Swing-Johnson bill. No other conclusion could be reached, after examination of the findings of the various committees appointed by authorities in California, than that the utmost care must be exercised in ascertaining the safety of a damsite before selecting it for water storage. This Congress has thus far failed to do in the case of the Boulder Canyon damsite. It must be done before a dam is built at that location. The Commission considers your work very creditable and your interest most praiseworthy. We welcome any assistance from loyal Arizonans, but especially so when it takes the form of information, supported by facts and figures. COLORADO RIVER COMMISSION OF ARIZONA, Very truly yours,

By Mulford Winsor, |

SEE ALSO:

Transcript of Coroner's Inquest

Hall of Justice 1928

Verdict of Coroner's Jury

Arizona Report 1928

Popular Science 1964

• Rippens Story of Dam Disaster (1998)

Vital Lesson for Today (ASDSO 2018)

At Dam Site 3-14-1928

With Van Norman at Dam Site 3-15-1928

Coroner's Jury Inspects 3/1928

Hall of Justice 1928

Fountain 1940s

Aqueduct Memorial Garden Opens at Mulholland Fountain: Story 10-23-2013

Mulholland Fountain & Aqueduct Garden: Photo Gallery 11-10-2013

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.