|

|

Emma Benson, LASD

First Female On-Duty Deputy Killed in U.S. (1919).

By John Stanley and Mike Fratantoni

| Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department

|

On Saturday, Oct. 13, 2012, at the now-closed Sybil Brand Institute, the Los Angeles Sheriffs Museum will honor the 100-year anniversary of the hiring of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department’s first sworn female deputy sheriff, Margaret Q. Adams. Margaret Queen Adams was sworn in by Sheriff William Hammel in 1912. Having separated from her husband, she needed work to support her two children. She served in the Civil Division of the Sheriff's Department for 35 years, retiring at age 72. Saturday's event will also honor the 40-year anniversary of women being assigned to work in patrol and the 20 women trailblazers who were the first to work the streets in marked patrol cars. These accomplishments are incredible milestones for women of the Sheriff's Department. On Oct. 13, those who join us at SBI will learn much more about the women who merit the praise for them, but before these triumphs could occur, hundreds of other women toiled in obscurity, breaking the hard ground to make them possible.

One such woman was Deputy Emma Benson. Until very recently, we knew nothing about Emma. With our discovery of her story, not only did we learn about another early LASD female pioneer, but about a woman who will now be recognized as the first female deputy sheriff to lose her life in the line of duty in the United States and the first woman peace officer to merit that honor in California. Deputy Benson was hired in 1918. She was unmarried and was approximately 41 at the time, although the matter of her age would be handled very delicately after her death. Like Margaret Adams, she was the sister-in-law of the sheriff. In her case, her brother-in-law was Sheriff John Cline. But unlike Margaret Adams, Emma could not be hired by the sheriff simply because she was a close relation. She first completed and passed a civil service exam for the position. By so doing, she thus became the department’s third female deputy sheriff. In 1916, Deputy Nettie Yaw became the first woman to enter the department after completing the civil service exam and was assigned to the department’s Criminal Division. While Deputy Adams worked exclusively in the Civil Division throughout her career, Deputy Benson, like Deputy Yaw, worked more challenging assignments. Notably, Emma was involved in the transportation of female prisoners.

It was while returning from one such escort to the Norwalk mental health hospital on March 20, 1919, that Deputy Benson was killed. The car she was riding in was struck by a Pacific Electric car at the Rio Hondo crossing on Telegraph Road in what today is Pico Rivera. Also killed in the collision was the vehicle’s driver, Deputy Sheriff Harry Guard. Another deputy, Maurice Reyes, was riding as the rear passenger and was severely injured, but he survived. Numerous newspapers described the collision. It was a clear afternoon with good visibility. The railroad crossing wig-wag signals were observed to be operating properly. The papers noted that Deputy Guard was the sheriff’s chauffeur and was considered an excellent driver. In 1919, driving cars was still not something most people did. Deputy Guard had been assigned this task for more than a decade.

From the accounts of witnesses, it appears that Guard underestimated the speed of the eastbound Pacific Electric trolley. A Ford Model T was the vehicle the three deputies were riding in. Given the gross disparity in weight between the trolley and the car, it is easy to understand why Deputies Benson and Guard were killed instantly. It is remarkable that Deputy Reyes survived.

The newspapers noted that Reyes was in charge of the department’s “Spanish cases.” Both of his wrists were broken, as was his right leg. He also suffered internal injuries and a fractured skull. He was not expected to live. However, despite his injuries, Reyes not only recovered, but lived a long life and passed away in 1973. Prior to lapsing into unconsciousness, Deputy Reyes was able to tell Undersheriff Zehner some details of the crash. Approximately 50 feet prior to the crossing, he saw the Pacific Electric trolley and yelled, “Look out! There is a car!” But Guard did not stop. This account matched the statement made by the Pacific Electric car’s motorman, E. Wittman. He said he had no idea how the accident occurred. The automobile shot out in front of him before he could apply the brakes. The trolley ripped the front wheels off of the car and dragged it a considerable distance onto a bridge before Motorman Wittman was able to bring the trolley to a stop. Deputy Guard was survived by his wife, mother and two sisters. He was 38. All of the newspaper articles stated that Deputy Benson was 25. Her death certificate, unlike Deputy Guard’s, lists her age only, and not her date of birth. It was attested to by Sheriff Cline, and said she was “about 39.” Yet the headstone over her grave shows that Emma was born Sept. 30, 1876, which made her 42 at the time of her death. Emma was a single woman. Given the spirit of the day, it was a conceit to make her appear younger than she was. This might also explain why the Los Angeles Examiner newspaper used a photo of her when she was much younger than at the time of the accident. The paperwork acknowledging the line of duty deaths of Deputies Benson and Guard were submitted to Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca for his signature, and as a result, both of these deputies will be recognized at next year’s peace officer memorials. At that time, Deputy Benson will be formally acknowledged as the first female deputy sheriff to lose her life in the United States and the first female peace officer to suffer this fate in California. To honor her life, and the accomplishments of the many women who served the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department with distinction for more than a century, we invite you to join us on Saturday, Oct. 13, 2012, at Sybil Brand Institute.

|

SEE ALSO:

Constable A. Harnischfeger, St. Francis Damkeeper's Father

E.O.W. 3-20-1889

Constable McCoy Pyle

E.O.W. 4-24-1897

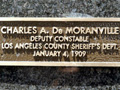

Deputy Charles De Moranville

E.O.W. 1-4-1909

De Moranville's Killer Walks: News Reports 1909

Deputy Ed Brown

E.O.W. 9-14-1924

Deputy Ed Brown

E.O.W. 9-14-1924

Constable Jack Pilcher

E.O.W. 6-4-1925

Constable Jack Pilcher

E.O.W. 6-4-1925

Deputy Arthur E. Pelino

E.O.W. 3-19-1978

Deputy Jake Kuredjian

E.O.W. 8-31-2001

Deputy David March

E.O.W. 4-29-2002

Kuredjian, March

Sacramento Memorial

Deputy David March Memorial Interchange

Matthew Pavelka BPD

E.O.W. 11-15-2003 SEE ALSO:

Deputy Emma Benson

E.O.W. 1919

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.