|

|

George Moran Sues 'Two Black Crows' Partner Charles Mack

Vaudeville Actors; Newhall Resident (Mack)

Click image to enlarge

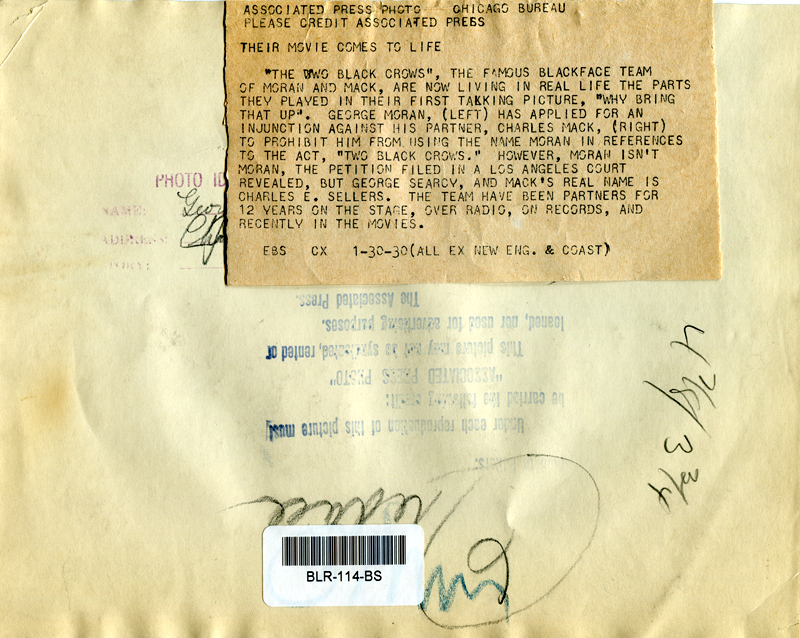

Associated Press wire photo (1930) from the archives of The Baltimore Sun, showing the blackface comedy duo of George Moran (left) and Newhall resident Charles Mack — known as Moran and Mack, aka The Two Black Crows. Moran was dissatisfied with the salary he earned for his role in the first movie featuring the Two Black Crows, 1929's "Why Bring That Up?" Moran walked away from the act; Mack responded by hiring Bert Swor to replace him and dubbed him the new "Moran," thus preserving the name of the act. Moran filed an injunction in an attempt to block Mack from using the "his" name. But just whose name was it? Original AP cutline on this wire photo of Jan. 30, 1930, reads:

ASSOCIATED PRESS PHOTO CHICAGO BUREAU

THEIR MOVIE COMES TO LIFE The Baltimore Sun ran this news item in its Feb. 9, 1930 edition, as indicated by the date stamp on the back (not visible in this scan; it's covered by the cutline, which is folded over it). What they're actually doing in this photograph, which appears to be a studio production still that was repurposed as a wire photo, is not explained. It looks like they're holding some sort of construction blueprints. Moran and Mack — more correctly, Searcy and Sellers — resolved their disputes. They appeared in at least four more films together and were traveling together from New York to Los Angeles when their car crashed in Arizona. Mack died. Moran and others in the car survived. The barcode on the back of this photograph is that of the 2013 photo seller.

About Charles E. "Charley" Mack. Charles Mack was born Charles E. Selders in White Cloud, Kansas, on Nov. 22, 1887, but he grew up in Tacoma, Washington. He was half of the "Two Black Crows" blackface vaudeville team with George Moran, and he built a compound of three houses in Newhall where he lived in the 1920s and '30s. By his own account, Mack played professional baseball as a young man in Olympia, Wash., where he was known as "the man in the iron mask" (he was a catcher). "The street car company owned the ball club," he writes, "and in my spare time I was a conductor on the cars. This so electrified me that I got a job as an electrician in a Tacoma theatre, my first experience in show business." "Sometimes the actors ran out of juice," he continues, "and I supplied it to them in the shape of new acts. After a while I thought that as long as the actors liked my stuff I might as well write an act for myself and be an actor. So I scraped some black off the kitchen stove and went on the stage. I didn't have nerve enough to do it whiteface." Mack — who signed his name "Charley Mack" — hired John Swor as his first partner and eventually hired Moran to replace him when Swor left. "Since then I have called my act Moran & Mack — The Two Black Crows. Vaudeville audiences both here and in England seemed to like it," he writes. Among their notable appearances were with W.C. Fields in vaudeville, and in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1920 and Earl Carroll's Vanities on Broadway. "Phonograph records, based on my acts, made noises in about 7,000,000 homes," he writes. "I also got into a lot more million living rooms through the radio." "The Two Black Crows" became a weekly radio show in 1928 and centered around corny (and usually non-racial) jokes and gags. Like their 1929 Paramount comedy of the same name, one of their catch phrases was "Why bring that up?" It was Mack's retort when Moran would remind him of something better left forgotten. Another was, "Who wants a worm, anyhow?" — Mack's retort when Moran would tell a parable ending in the admontion, "The early bird catches the worm." Mack also wrote a novel in 1928, "The Two Black Crows in the A.E.F.," which Paramount turned into the 1930 Mack & Moran picture, "Anybody's War." Meanwhile, Newhall was close enough to Hollywood yet remote enough to serve as a getaway. Mack built himself a unique gingerbread home in the French Norman style on 8th Street, west of Market Street, around 1924, and added two smaller cottages at the end (top) of 8th Street. Collectively the compound was known as Crowland. Mack entertained the likes of William S. Hart, Noah Beery, his partner Moran, and many other celebrities. Moran and Mack's entry into movies at the height of their popularity caused a rupture. Moran reportedly sued Mack in a salary dispute over 1929's "Why Bring That Up?"; the court ruled that Mack owned the act and could set the salaries. Moran left and Mack replaced him with John Swor's brother, Bert Swor, who became the new "Moran." George Moran sued in January 1930 to block the new duo from using "his" name, but court documents showed that Moran wasn't George Moran's real name; it was George Searcy. The turmoil in the partnership was short-lived. Charles Mack and George Moran appeared together in at least four more films from 1930 to 1933, and Moran was in the car when Mack died in a crash in Mesa, Ariz., on Jan. 11, 1934. Also in the car was film pioneer Mack Sennett, who had attempted a comeback in 1932 when he directed a Mack and Moran picture, "Hypnotized." The group, which included Mack's wife Myrtle and daughter Mary Jane, was reportedly en route back from signing a contract with Columbia in New York. The others weren't seriously injured. Following Mack's death, W.C. Fields lived in Mack's main 8th Street house for a short time (circa 1935-36). Moran tried to revive the Two Black Crows with different partners, without success; he did appear in two later W.C. Fields films: "The Bank Dick" and "My Little Chickadee" (both 1940); "Chickadee" is said to have filmed in a house at Monogram Ranch, later called Melody Ranch, in Placerita Canyon. That same year, Monogram exec Ray Johnston purchased Mack's main house on 8th Street. He sold it in 1943. "Our" Charles Mack should not be confused with 1920s actor Charles Emmett Mack, who died in a 1927 car crash. Further reading: 8th Street Home Popular with Vaudeville Greats. Further reading: Architect Sues Mack for False Claims About 8th Street House Designs, 1931.

LW2337b: 9600 dpi jpeg from original 8x10 print purchased 2013 by Leon Worden. |

Charley Mack

Newhall House Story

Letter Authorizing Construction 7-16-1929

Mack's 1928 Novel

"Why Bring That Up?" 1929 (Mult.)

"Anybody's War" 1930

Moran & Mack Lawsuit 1930

Paramount Ad 1930

In Character 1931

Architect Sues 1931

Sues Ex-Secretary for Embezzlement 1932

Wm. S. Hart & Charley Mack in Newhall 1933

Wallace Beery, Hart, Moran, Mack in Newhall 1933

With Wm. S. Hart in Newhall 1933

With Moran ~1933

W.C. Fields at Mack House ~1935

Main House

22931 8th St.

Other Mack Hous

23021 8th St.

Other Mack House

23031 8th St.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.