|

|

The Bogus Story of Tom Vernon and the Sweetwater Incident.

By Carl W. Breihan.

Golden West magazine | July 1967.

|

Webmaster's note.

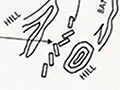

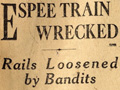

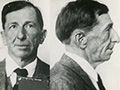

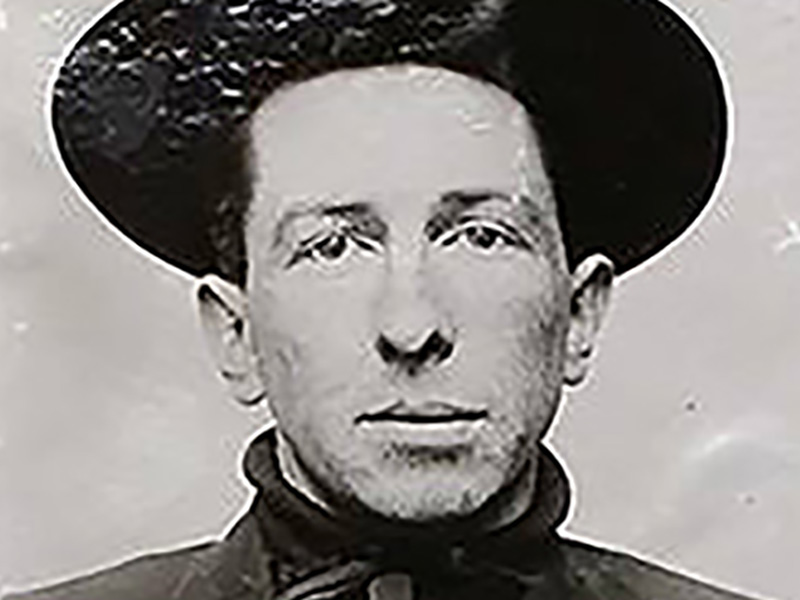

The last line of this story reads: "Never has a TV thriller equaled the actual experiences of Tom Vernon." We would offer a different ending: "Never let the truth stand in the way of a good yarn." This story is bogus. It takes an already bogus story — the fabricated justification for the murder of Jim Averell and Ellen Watson — and compounds it with additional layers of absurdity. Yes, there really was a Jim Averill (actually spelled Averell), who was an upstanding citizen of Carbon County, Wyo., having been appointed postmaster by the president of the United States and justice of the peace and notary public by the Wyoming governor. Yes, Averell really did live with a woman named Ellen Watson — a divorcee whom he had secretly married. Yes, there really was a Cattle Kate, but she wasn't Ellen Watson. She was Kate Maxwell, a madam who lived a horseback-ride away from the Averells. Yes, Jim and Ellen (aka Ellie and Ella) really were killed by a powerful cattle syndicate on a (false) charge of cattle rustling, after the syndicate made a dubious claim to a few dozen head of unbranded calves (aka mavericks or dogies) that Ellen branded — after having purchased them. Yes, both before the killing and afterward, the syndicate purposefully conflated Ellen with Kate, falsely accusing Ellen of being a prostitute and Jim her pimp, as part of the syndicate's campaign to discredit and drive out homesteaders who legally fenced in formerly open-range land that the syndicate was using but didn't own. The lynching was really about land rights, not cattle rustling. There were partisan overtones, as well, Averell being a Democrat and the cattle barons being Republicans. (The Sweetwater incident was one of many precursors to the Lincoln County War and provoked at least two Hollywood films including the 1980 box-office flop, "Heaven's Gate," starring Kris Kristofferson as James Averill [cq].) And yes, there really was a boy who witnessed the execution and got away. Raised by Ellen as her adopted son, he was 11-year-old Gene Crowder, son of a down-on-his-luck rancher named John Crowder. (He was twice the age of our Tom Vernon, who had nothing to do with anything and was nowhere near Wyoming.) An even older boy, a 14-year-old ranch hand named John DeCorey, was also on scene. He, like other witnesses who feared for their safety, fled the area afterward. How did the murder of two homesteaders get turned around to make it their fault? Quite simply, it was the work of the reporter Edward Towse, who broke the story in the Cheyenne Daily Leader, the region's largest newspaper. The Leader was controlled by the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, whose members eliminated the Averells — who were becoming a bigger and bigger problem for the stockmen by actively promoting the settling of the Sweetwater Valley by other homesteaders. Rather than the hanging of cattle rustlers, which they weren't, their lynching would have been more justly treated as a cop killing, considering that Averell, who had been a sergeant in Gen. George Crook's 9th Infantry, was the duly appointed law in those parts. (See the excellently researched Hufsmith 1993 for the full account.) The rest of the story, as told here, was hatched from the mind of a two-bit drifter and inept horse thief (he kept getting caught) who was known to the California penal system as Thomas Vernon. Today we would call it identity theft. It's a mish-mash of two people — apparently Gene Crowder, and a flash-in-the-pan rodeo star named Jesse "Buffalo" Vernon — whose identities were stolen by Vernon (whose real name may have been Walter Brugler, originally from Pennsylvania). No credible history of Jim Averell and Ellen Watson suggests they had a child of their own or reports the presence of a boy who would have been 5 at the time. What we do know is that one night in 1929, Tom Vernon derailed a train in Saugus., Calif., and robbed its passengers, then fled to Wyoming and did it again before he got caught. Did Vernon, alias Brugler, steal Gene Crowder's story while he was robbing that second set of passengers in Wyoming? Or did he already know it? The "Cattle Kate" story was the stuff of pulp novels (passed off as non-fiction) and widely told. Either way, he knew it fluently when he inserted himself into it shortly after his capture. For nearly three decades in Folsom Prison he stewed on it, massaged it, embellished it, then tried to peddle his story to newspapers and magazines in his final years while he was living in a Sacramento flophouse. At last, things were looking up for old Tom. Some newspapers picked up his story, and then Golden West magazine published the whole saga in its July 1967 edition. One month later, on Aug. 18, Tom Vernon died. For decades after that — before there was such a thing as the Internet with open access to searchable databases of birth, death, census and prison records — a fictitious amalgamation of "Buffalo Tom Vernon Averill" wormed its way into Santa Clarita Valley history. Heck, there were even newspaper stories (quoting Vernon) to back up magazine articles about this multitalented and pitiable soul. At the end, we take it back. Golden West magazine had it almost right. Rarely has a TV thriller equaled the imagination of Tom Vernon. Nobody would believe it. Nor should they.

Tragedy on the Sweetwater.

Golden West magazine | July 1967.

Many a young TV viewer today concocts a gruesome day dream as he wonders how much hardship he could have endured if he had lived in the days of the Indian frontier battles. But no such daydream has ever equaled the true experience of Buffalo Tom. This was the boy who was exposed to murder by supposedly civilized white men and miraculously saved by supposedly savage Sioux Indians in the Dakotas. Tom Averill grew up to become famous as Tom Vernon, the buffalo rider in the Wild West Shows which were staged throughout the world by Buffalo Bill Cody. Knowing that his life story was too fabulous to be easily believed, Tom went to considerable trouble to document his claims regarding his birth and the death of his parents. It was Tom's aim in life to vindicate his mother and father from the false and scandalous reports which the cattle barons spread in their campaign to sweep the plains of homesteaders so as to keep an open range. And Tom succeeded in correcting the record. He even left to posterity a list of names of the Wyoming cattle syndicate members who had engaged the killers to do their bloody work. Until Tom was eight years old he lived in a neat little log cabin behind a general store which his father, Jim Averill, had established on the Old Oregon Trail near Independence Rock, in Carbon County, Wyoming. He played in the lush bottomlands of the Sweetwater River and thought that life was wonderful on the green prairie where his parents had each homesteaded 160 acres. His mother, Ella Averill, the daughter of Missouri pioneers, had the pluck of the best pioneer women. She labored beside her husband to improve their home year by year. They raised vegetables, cows and horses. The haphazard business at their store developed more and more as numerous homesteaders moved into the region. It looked to the Averills as though their hard work had put them on the road to success, and all their neighbors within a radius of fifty miles respected them for their fortitude. But the range had previously been open to the roaming cattle of the big outfits. Now, as each homesteader fenced his 160 acres to meet the government's requirements, he was marked as an enemy. There was no doubt that enough homesteaders and enough fences would wreck the business of the cattle barons. Therefore these men ruthlessly undertook to discourage the settlers. There was only one way of preventing new pioneers from staking claim to this land: frightening the homesteaders already here into leaving, and making it clear to others that the dangers were too great to surmount. It was not difficult to hire men without scruples who would, for a price, carry out a campaign of threat. Nevertheless, the threats did not intimidate the hardy settlers, who felt that the final chips were down, and grimly waited to be dealt the last hand. Then it was that the organized cattlemen resorted to tangible harm, creating horrible examples of what awaited settlers who dared to enter the region. Tom was not too young to sense the grip of fear as various settlers stopped at the general store, which was also a post office, to make purchases and confide their troubles to Jim and Ella Averill. He listened with the same dramatic suspense that a boy of today watches a TV story about cowboys beating rustlers to the draw. It was exciting, but it seemed far away from reality, and Tom did not take it too seriously for a long time. Finally, however, even a boy of eight could not ignore the evil undertones, especially when threats were acted upon, bringing murder and ruin. When one after another of the homesteaders had been threatened with death if he did not move westward, and later had been found dead in a gulley, nobody could consider such a string of disasters as isolated incidents. The homesteaders soon realized that a systematic campaign was directed against them and none of them was exempted from the attacks of their powerful opponents. The crime of the settlers was in their making use of a part of the range which the cattlemen were determined to keep for themselves. Regardless of government approval of their claims, regardless of the hardships by which they had paid for their 160 acres apiece, their rights as landowners on the prairie were never to be respected by the big cattle barons. Whenever Tom heard about fences torn down and cattle driven off to places where they were never seen again, he felt both defiant and vengeful. Constantly he heard about whole wheatfields or barleyfields that were burned in the night. Barns and dwelling places were repeatedly left in ashes. In order to save their lives the settlers had to flee. Gradually, Tom was consumed with fear and furious anger at the same time. One of the reasons for this complex of emotions was his helplessness to do anything to correct the injustice. Even the grown-ups failed in all their efforts to forestall the arson and murder of the hired guns. Jim and Ella Averill steadfastly refused to run when they were threatened, and Tom looked upon them with wonder at their courage. Jim Averill was a short, thick-set man who relied upon his own integrity and who, even when recognizing the danger which hovered over the whole region, believed he could win out against the cattle barons. His wife stood shoulder-to-shoulder beside him and practically stiffened his spine by her own courage. Tom's fear almost evaporated when he saw his parents refusing to join settlers who left in their last wagons. He admired the way they stood by their rights, ready to face whatever battles they had to fight in order to protect their homestead. Jim Averill was a well-read man, and one of the reasons that the cattle barons first marked him as a danger to their plans was that he had read and digested the laws which defined the rights of homesteaders. The killers could frighten men who were not entirely sure of their legal rights, but Jim Averill could answer them back by quoting a pertinent section of the Wyoming code. Worst of all, Jim Averill subscribed to eastern newspapers. He read the false reports which the big cattlemen spread against the homesteaders. According to them every settler was a thief and a liar. In turn Jim Averill wrote letters to the newspapers correcting the false reports, explaining the case for the homesteaders, and his letters were printed in the same columns. However, his feeble voice was not equal to the organized campaign in the newspapers. It was merely accepted by the cattlemen in Wyoming as a warning that Averill was a man they had to blot out. They recognized him as the spearhead of the opposition to their unjust monopoly of the land. The homesteaders were acquainted with the Board of Livestock Commissioners who were always finding some excuse to prove that their fences were in the wrong place or that they had not legally proved up on their claims. Even though the homesteaders had government papers to back up their claims, they were constantly flouted by men who sided with the cattle barons. There was another organization called the Cattlemen's Association, but this was composed of the same men who made up the membership' in the Board of Livestock Commissioners. First one group claiming to be from one "official" combination and then another group claiming to be from the other would ride up to a ranch and demand what they called their rights. The average settler was completely confused by the legal accusations hurled at him, and if he held out for a while it was only to meet more deadly measures. After their threats the cattlemen sent their hired guns to use fire as a deadly hint that a settler had better not stay. If the burning of all his possessions did not convince him, then he was shot when he went to round up his cattle. Widows and children, after such episodes, usually found some way of getting out of the prairie, and it did not matter to the big outfits where or how they went. Their whole object was to clear the prairie so that their cattle could roam on a never-ending pasture, otherwise they could not retain their power and importance. One "accident" after another made the prairie a hell of fear, and no man with a family dared to risk their welfare. Family after family withdrew toward the west, hoping to find government protection in some spot not being stifled by the big cattlemen. Jim Averill decided that the homesteaders ought to organize for their own protection against the Board of Livestock Commissioners and the Cattlemen's Association, so one day he called a meeting in his trailside store. Settlers from many miles around came, to discuss ways in which they could get government protection or in which they could help one another to continue on their farms. But the only result of this meeting was that Jim Averill became more than ever the marked target for the barbs of the syndicate. The settlers had brought their families through, hundreds of miles on starvation rations. They had fought Indians and had seen their loved ones die of wounds or sickness before they arrived on the prairie. They had continued to starve and had worked with a superhuman effort in order to prove up on their acres. Moreover, they were still without comforts and still lacked bare necessities. But they were willing to hang on, through natural miseries, in the hope of eventual success. However, to live through evil attacks by men determined that they should never enjoy the land on which they labored, regardless of their legal rights, sickened them. For a piece of their own land they were willing to suffer, but against the "bloated octopus" of their organized enemies they felt helpless, and they chose to flee. Despite (even because of) Jim Averill's newspaper letters, and despite his letters to the Land Office in Washington, the situation became more and more desperate. After all, near neighbors had been burned out or shot, one family after another had been glad to get away in a bare wagon after their other possessions had been destroyed. The Averills still held out, but they felt the pressure increasing as one effort after another was made to catch them in a position that would justify one of the henchmen in killing them or in dragging them off to jail. Once a stranger was brought into the store by Black Mike, a man in the employ of the cattlemen. The stranger had been told that Ella Averill was Cattle Kate, a rustler and woman of loose morals. He made advances toward her which might have been calculated to inspire Jim Averill to start shooting. Jim himself would then have been shot from behind, the blame left upon him for having drawn first. But in this instance Jim beat the stranger with his bare hands and thus got rid of him. Another time Black Mike tried to encourage Jim to sell whiskey to an Indian. That would have been another excuse to march Averill off to jail. Tom saw one family after another come by to explain their leaving the range, then never saw them again. "They've burned me flat," was part of the usual farewell. "Just before dawn the fire started in the barn and the house at the same time. It started from burning arrows shot into the hay and through the house windows. The fields are black now. You better git, too, Jim. They'll git you next." "I'm staying," said Jim Averill. "We're staying," said Ella, standing beside her husband. Tom wanted to go along with this last family, because without them there would be no children for him to play with. But he was thrilled at the heroism of his parents. Besides, he had a hazy idea that he might grow up in time to conquer the organized cattle barons before they could do much more damage. As each family stopped at the store to say goodby, Tom heard the halfhearted remark: "If any mail comes, save it till you hear where we're at." None of the retreating families had any idea where they would go next or what they would do. Simply, they could no longer buck the opposition of the iron-willed cattlemen. Each time Ella Averill went out to the wagons to talk with the women, they were crying. They had begun to be afraid they would never again find a place of safety. Tom watched as his parents bade farewell to all the families whose land ringed the store in a radius of fifty miles. Before long the Averills were alone, their only hope of any communication with human beings lying in the trail by which travelers would be likely to pass. What Tom as a little boy could hardly understand was the crudest part of the enemy campaign: they had taken to smudging cattle brands and claiming that the homesteaders had rustled their cattle. Accusing them of being ruthless was the worst threat of all. Whenever a man was shot from behind, the cattlemen could always say he had been caught rustling and had run when accosted. No other explanation was necessary, and there was no defense for the accused. Jim Averill said, "I'll see that they don't plant any blotched brands on me. I've got eighty cows and twenty head of horse, right branded and registered, and everybody knows what I got. I'll ride fence every day if I have to." The next news to come was that Jim and Ella Averill had been reported as outlaws. The claim was that they had made a deal with a tribe of Indians and had been driving stolen cattle by the hundreds to the Dakotas. Jim Averill considered this with a determination to find a way to clear his name — but when he heard that it was rumored he and Ella had never been married, then his anger couldn't be controlled. "They better stay off that tack!" he shouted. But he could not name the "they" and he could not shoot or strangle his vague mysterious accusers. Next there was a night fire in the store — most accidental, of course, though Jim Averill found that a kerosene-soaked rag had started it while he and his wife and son were asleep. He decided not to make any accusation, since he could not name the arsonist. But he had heard the flames crackling in time to rise and save the barn, and as soon as possible he rebuilt the store and the hut in which the family made their living quarters. When settlers rode over to help, Jim Averill said carefully, "Must have been a faulty flue." One of the ranchers said, "Yeah, I've done a pile o' traveling before I hit the Sweetwater. And I heard a lot about them bad flues all the way." Then he swung into the saddle and added, "There's gonna be a powerful lot o' bad flues from here on. You folks got my sympathy." Jim Averill — he begged lynchers to free Emma. The next thing that happened was the loss of Jim Averill's eighty cows — through a broken fence, though that fence had been whole the day before. He trailed them to a gully where he found the eighty of them shot dead. Jim kept his horses close to the barn after that, feeding them the hay that should have been kept for the winter. He never let himself sleep at night but roamed about with his rifle, doing all he could to protect his place. But the rumors continued, and the thing Jim Averill suffered most about was the spreading tale that his wife was Cattle Kate, a rustler and a bawdy woman. There was no way he could fight back. Finally a dust cloud in the distance turned out to be fifteen riders booted and spurred, wearing leather chaps and flat-crowned hats with thongs under their chins. These were no ordinary cowboys but strangers brought to the prairie on salary from the cattle barons. And today their leader was Black Mike, the most notorious of all the hired thugs. They came raging into the store, and Black Mike said, "We give you warning enough, Averill. So now we've come to arrest you for rustling and for blotching brands and running other people's stock into the Dakotas. We're the law." "Law nothing!" said Averill. But the men trussed him up, and they did the same to his wife. When young Tom tried to defend his parents by kicking and biting at the men, he was knocked aside. Through dirt and tears he saw Black Mike reach for him and grab him by the collar. Kicking and screaming, Tom was tossed across Black Mike's saddle and pressed against the horn, the wind jolted out of him. He was roped and forced to ride along with the marauders after they clattered out of the store, dragging Jim and Ella Averill whose hands were tied behind their backs and whose legs were hobbled. The riders got their three victims into the shadow of a cottonwood grove, and then for the first time the boy knew exactly what had been planned for his parents. He saw his mother lifted to the back of a horse and the thongs cast from her ankles. Black Mike said with a sneer, "Ladies first." One of the horsemen drove alongside Ella and placed a noose over her head. He coiled the long rope and tossed it over a limb of a cottonwood tree. Another man seized the dangling end of the rope and dropped two half hitches over the horn of his saddle. Jim Averill cried out, "There's no good swinging a woman. Let 'er go — swing me if that's what you want." Black Mike answered, "She's in this as deep as you. And after you two we'll take your young whelp and swing him by the fetlocks and bash his head on a wagon hub. That'll get rid o' the whole layout. Ain't leavin' no whelps in this coyote den." At this Tom's mother let out a piercing scream. "Pull that critter up an' let 'er swing," Black Mike commanded. The man who had tied the rope to his saddle spurred his horse, while another man struck the horse on which Ella had been seated. The rope horse swung sideways and braced all four feet just as Ella was unseated. She hung, her face swollen and black, her legs jerking spasmodically, while young Tom looked on in frenzy. While they lowered the dead body one of the men removed the hobbles from Jim Averill's feet in preparation for swinging him, too. Jim made a dash to escape. But he was tumbled by the crowd and beaten with gun barrels, so that his broken jaw hung bleeding when young Tom got his next sight of him through the melee. Tom cried frantically, "Dad, Dad! I'm here!" But he was completely helpless. Black Mike heaved a fist at him and he landed against a tree trunk yards away. When he was able to open his eyes, he saw his father swinging. The rope horse again plunged and blocked with stiffly braced legs. Jim Averill's legs jerked wildly at first, then more and more slowly, until there was only a rigid twitching. Black Mike watched the hanging man as if he were in a trance. But when he was sure that Averill was dead he turned to young Tom. In spite of Tom's kicking and screaming, Black Mike got him by the shoulders, then swung him upside down, seizing his ankles. He swung the boy like a pendulum, and Tom was no longer able even to scream. He felt himself giddying back, aimed at a tree trunk, and he knew his head was about to be bashed. But suddenly two hands caught at Tom's shoulders in the middle of the final swing. "Let go, Mike. I don't go for kid killing," cried one of the men. Tom was almost out of his mind. He had given himself up and by now had lost all sense of hope. But he heard what the men were saying about his parents: "Leave 'em for the buzzards." Black Mike was still arguing about Tom: "He's a witness. What you gonna do with 'im?" "We'll ditch Mm when we get to the Dakotas," said the other man. "Let the Injuns find him. It's their funeral what they do to 'im." Tom was then hoisted to the saddle in front of the man who had saved him, and he was almost too numb from pain and anger to think straight. He was frozen silent, but he was shivering so that he could hardly sit on the front of the saddle. The men took him back to his parents' home and held him roped while they looted the place. In the barn they caught his own pony and tied him to the saddle. In the meantime he watched the men opening his father's stock of whiskey and gulping down the stuff as they packed as much of the other merchandise as they could into their saddle bags. And then he saw them set fire to the store and the barn. The crowd moved off, Tom on his pony dragged along by a rope which one of the riders held. All he knew now was that they were headed for Dakota where they would throw him to the Indians. He was beyond fear for the time being, almost crazy with grief and horror. The blows he had received were so painful that several times he blacked out. But he was being dragged along, and the men made camp twice before they spotted a dugout with a rotted log roof. "Here's a good place to leave the runt!" cried one of them. They talked about the nearby Indian tracks and decided that the boy might be found sooner or later if they left him here. Black Mike, however, insisted on tying Tom inside the dugout with a piece of chain and some wire to make it impossible for him to escape by himself. When Tom was secured and the riders had left, he was trying to muster up the strength to call for help — when he saw Black Mike sneak back to the dugout and grin at him. Black Mike aimed his gun and fired. In the dugout the explosion roared like doomsday, and Tom felt hot pain in his throat. He blacked out for many hours. When he regained consciousness his feet and legs were stiff and he was shivering in the dark and the cold. He tried to stir. At the rattle of the chain he suddenly remembered the whole terror, while pangs shot through his body and the pain in his jaw and throat seemed unbearable. In spite of the pain he tried to shout. He shouted at intervals, every time he could make himself brave enough to stand the pain which was caused when he used his throat. After daylight had seeped into the dugout he heard what may have been a footstep, or it may have been only the snapping of a twig. He was afraid it meant the approach of some wild animal, and a new terror overtook him. But in the full flood of sunlight he made out the head and shoulders of a human being slowly crouching down to look at him. Evidently his weak shouts had been heard. At last he saw that the head had a ragged scalp lock from which hung a single eagle's feather. The face beneath it was streaked with white and vermilion paint. Tom's terror mounted. Without realizing what he was doing, he felt that he ought to run, unreasonable though that was. And the slightest movement of his limbs made the chain rattle. Evidently that frightened the Indian. At any rate, the head and shoulders disappeared. Tom lay in rigid silence, and minutes later the Indian returned. Tom saw the Indian creeping toward him and he held his breath in the worst fear he had yet experienced. The Indian carefully inspected the way Tom was tied, and working the wire with his teeth and his fingers, he was able to free the boy. He carried Tom into the sunlight and unfastened the thong on his wrists. He tried to get Tom to stand, but Tom fell in pain and exhaustion. Thereafter the Indian carried him against his musky brown hide, and for the first time Tom realized that he was safer with this savage than he had been in a long, long time. When Tom saw the hides stretched between the tepees on poles, he knew that he was in a Sioux hunting camp. He saw brown children and square-faced squaws gather around to peer down at him. He was placed on a hide on the ground. A band of braves came running to inspect him, and their leader was wearing an embroidered vest. This leader attempted to say some words in English, and though Tom could hardly make his sore mouth speak, he managed to say, "Black Mike shot me." Inquiringly the Indian pantomimed the shooting of a rifle, and Tom nodded. A buxom squaw lifted Tom in her arms and carried him into a tent, placing him on a mat of buffalo skins. She bathed the gun wound in his neck and crooned over him. Then she placed hot poultices on his jaw, and he felt soothed by the fragrance of herbs. A few days later the Indians managed to call Dr. Glennan from the U.S. Eighth Cavalry. Gradually Tom grew stronger under the loving ministrations of Morg, the squaw. He learned that the Indian in the beaded vest was Chief Iron Trail and that the one who had found him in the dugout was called White Eagle. Dr. Glennan explained that it was necessary for him to remove the bullet from the back of Tom's neck where it had lodged after striking his jaw. This was evidently such a painful operation that Tom never afterward remembered it. He probably blacked out while the doctor was working on him. Dr. Glennan had the idea that if the man who had shot Tom ever heard that the boy was alive, he might come back to kill him. Therefore, he cautioned the Sioux to guard Tom carefully. Everybody seemed to doubt that Tom could have come from such a faraway place as Sweetwater, and he did not have enough strength to insist. Actually, he was unable to talk to anybody about the horror he had witnessed. Whenever he was questioned he found it impossible to force his lips to report all that had driven him nearly out of his mind. Tom regained his strength and learned to like the Indian children who played with him and told him the Indian names for things. Within six months he was as tanned and as wild as his playmates. One day when he seemed to have completely forgotten the old terror, he saw his playmates disperse like quail and disappear in the undergrowth along a stream. But We-No-Na, an Indian girl, grabbed him by the wrist and tried to drag him to safety. Then Tom saw that a horseman had suddenly appeared — and that it was Black Mike. He pointed to his jaw scar in order to make it clear to We-No-Na who this man was. She shrieked like a screech owl, just as Black Mike dismounted and grabbed the rawhide band around Tom's waist. He tossed Tom across his saddle and put his foot into his stirrup to remount. Tom sank his teeth into Black Mike's hand and started to kick. During the renewed screeching of the children, and while Tom was fighting furiously, Black Mike heaved himself into the saddle. Suddenly a husky voice cried, "Let him go!" Black Mike started to grab his whip. But an Indian named Pete hurled himself from his own pony and with one arm around Black Mike's neck dragged the desperate killer off his horse. Tom, too, tumbled off and rolled over and over until he was out of the way of the hooves. Then Tom saw Black Mike fighting for his life, while Pete clung to him and slowly choked him to death. They rolled about in the struggle while Black Mike tried to get his spurs into Pete's legs. But Pete's wiry legs hugged Black Mike's abdomen while his hands were relentlessly at his throat. It seemed an age to Tom before Black Mike lost his strength. His eyes popped and his mouth sagged, his thick tongue bleeding in streams through his teeth. At last Tom saw the final quiver in the legs of that hated Black Mike and the last stiffening tremor of his arms. Pete slowly released himself from the heavy carcass, and by that time other Indians had arrived on their swift horses in answer to the screams of the children. The whole Indian village rejoiced savagely for Tom's sake, for by now he was one of them. And he grew up among them, learning from them to ride so well that he seemed to be part of his horse. They also taught him to make a lariat "talk," and for miles around he was known for his exceptional skill in training wild horses. When Buffalo Bill Cody was preparing one of his Wild West Shows, he engaged one hundred Sioux as well as Tom to put on an act. But Tom was only fifteen years old at that time, and it was necessary for Buffalo Bill to contract him through a legal guardian. The star of his show, the famous crackshot Annie Oakley, volunteered for that task. She was Tom's guardian until he reached the age of twenty-one. As soon as he reached manhood, Tom established his identity. He learned, among other things, that after he had been carried away from the cottonwoods where his parents had been lynched, cowboys had reported finding the smoky ruins of the Averills' store. The bodies of the Averills were not found in the embers. Therefore Tom C. Grant, who was known as Silver Tip, formed a posse of the settlers in the Sweetwater Valley and they rode out as a search party. They found the forlorn corpses in the cottonwood grove and gave the Averills a decent burial. But they had long puzzled as to the fate of Tom. When Tom was famous as Buffalo Tom Vernon, appearing in Madison Square Garden and many points west, he made public the names of the cattlemen who had hired Black Mike and the other marauders. But there was little satisfaction in this, since none of them was ever punished. In fact, some of them had amassed fortunes as members of the guilty syndicate, and they had left their riches to their kin. But the pioneers who had laboriously proved up on claims had been left impoverished with nothing to bequeath to their own loved ones. Nevertheless, the record stands. The only survivor of the Sweetwater Massacre was at least worthy of his brave parents in terms of his own courage and skill. He long performed throughout the country as a buffalo rider and a trainer of wild horses. Never has a TV thriller equaled the actual experiences of Tom Vernon. ◊

LW2992: pdf of original magazine purchased 2017 by Leon Worden. Download original images here.

|

Passengers / Earliest Known 11-10-1929

Daybreak 11-11-1929

Newsreel Footage

Loren Ayers x5

Boynton Story

Pollack Story

LAT 11-11-1929

Vernon Captured

Mugshots 12/1929

Extradition 12-12-1929

AP 12-19-1929

REAL: Tom Vernon Prison Records

REAL: Horse Theft 1920

BOGUS: Tom Vernon Letters 1929-1963

BOGUS: Tom Vernon's Fake Photo ID 1962

BOGUS: Vernon's Own Story in 3 Parts

BOGUS: Cattle Kate Story 12-7-1929

BOGUS: Vernon Retells Story in 1953

BOGUS: Sweetwater Incident 1967

BOGUS Sideshow: Lester F. Mead

'Confessor' 11-1929

REAL: Buffalo Vernon 1884-1939

1957-1958 x3

Pardon 1964

Death Cert. 1967

After the Wreck

No. 5042 x3

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.