|

|

Click image to enlarge

| Download archival scan

From left: William S. Hart, Ione Reed, George Palmer Putnam (Amelia Earhart's widower), Horseshoe Ranch, Newhall, California, 1938 (est.). Original BW print, 8x10 inches. Reed inscribed the photo (over Hart's shirt): "To [illegible] / From Bill & George too / We think you are swell / Sincerely, Ione Reed."

Publisher George Palmer Putnam made good on William S. Hart's invitation to visit him at his ranch in Newhall while Putnam's wife, Amelia Earhart, was away circumnavigating the globe. But when Hart invited him by letter in February 1937, neither man knew Amelia would be away forever — or that when Putnam finally accepted, he'd be bringing another woman to the party. The meeting must have occurred during the spring or summer of 1938, roughly a year after Earhart flew into the heavens. That is when Putnam had a short-lived relationship with Hollywood stuntwoman Ione Reed, who had recently gone through a stormy breakup with her stuntman boyfriend Cliff Lyons. Putnam was no stranger to Hart's Horseshoe Ranch. He and his missing wife had spent many an evening sitting on Hart's porch, watching one of Hart's Great Danes chase the "moon-struck bunnies" on the lawn, and viewing old Hart re-runs in the actor's living room.[1] On their own, Putnam and Hart probably had much to talk about. At the turn of the 20th Century, Putnam cut his publishing teeth as a swashbuckling newspaperman in Bend, Oregon, which was then the Western frontier. (While we generally reserve the term "swashbuckling" for the Santa Clarita Valley's own Scott Newhall, George Putnam fit the mold, from his feisty editorials that eviscerated politicians to his boosterism of his adopted community to his run for mayor — in Newhall's case, of San Francisco; in Putnam's case, successful. Putnam could have been the prototype.) Later, after World War I, when Putnam took the helm of the family company in New York, G.P. Putnam's Sons, he focused on publishing the adventure books of headline grabbers — from the African safaris of Martin Johnson (who, of local note, died in a 1937 plane crash in the mountains above Newhall) to the polar explorations of Admiral Richard E. Byrd, whom Putnam later used as a consultant on Earhart's flights. He even sold a story to Jesse Lasky at Paramount that became 1927's "Wings," first winner of a Best Picture Oscar. Five years later, Putnam was chairing Paramount's editorial board. Lady Lindy Dismissing certain earlier accounts as biased — "people either loved or loathed George Putnam" — Earhart biographer Mary S. Lovell[2] argues that Putnam was totally devoted to Earhart, whose career he managed. "Without George Putnam, my generation would have not heard of the name Amelia Earhart outside of aviation circles," Lovell writes in 1989. Many other female aviators (whom the author identifies) "are remembered with respect by those interested in American civil aviation, but I suspect few others would recognize their names. Yet all these women were contemporaries of Amelia and had to their credit great 'firsts' in aviation that at the time made headline news." Putnam was naturally drawn to intelligent and adventurous people. When their careers intersected in 1928, Earhart's cool poise and lanky, Peter-Panish figure (his words[3]) so reminded Putnam's employees of Charles Lindbergh that they dubbed her "Lady Lindy." But the way she handled herself, coupled with her "obvious ambition and dedication to her work and her enthusiasm for the future of aviation" — a common interest — although Putnam personally didn't like to fly — worked a magic that neither person anticipated or necessarily sought.[4] Their close work from 1928 onward fractured previous relationships as Putnam left a wife and Earhart a fiancé to be together.[5] During their courtship and subsequent marriage from 1931 to her disappearance in July 1937, there was no one else for George Putnam — even though Earhart had written to him when they married that she didn't desire or expect that kind of faithfulness.[6] It was a peculiar and unsolicited prenuptial agreement of sorts from a fiercely independent, feministic, career-minded woman. Putnam spent the remainder of 1937 — and went well into debt[7] — pursing and financing searches of the heavily shark-infested equatorial island chains where her plane could have gone down. In December 1937 he joined a sailing expedition to Central America. Lovell states that Putnam had a "commission to produce an illustrated book" that took him to the Galapagos Islands:

The expedition covered many weeks, and it was spring before he returned. "George," a friend was to tell me, "was capable of the full gamut of emotions." [The friend was Bob Lee, a writer who worked for Putnam.] His grief for Amelia was deep and real and it is not lessened by the fact that during those final weeks at sea he found solace in a relationship with Ione Reed, one of the women in the expedition. Given George's passionate nature it was hardly surprising that he would succumb in the confined nature of the expedition to a pretty and intelligent young woman who also found him extremely attractive. The two were discreet and the relationship continued for some months after their return[.][8]

Books and Boa Constrictors

It is unreasonable to believe Putnam and Reed had never met before boarding the boat. Contemporary news articles offer a different sense of the trip's purpose and destinations. Under a 4-column photograph showing a beaming Putnam and Reed with ship's captain Asa J. Harris at the helm as they're setting sail December 16, 1937, the Los Angeles Times described it as a zoological expedition to the South Seas:

The expedition will explore Mexico, Central America and Ecuador's Galapagos Islands in search of rare animals, birds and reptiles and will be gone three months. Collections will be presented to the California Zoological Society's Zoopark.[9]

The article doesn't explain what scientific knowledge the Hollywood stuntwoman brought to the table, only that Putnam compiled "a mystery box of a dozen books" for her to read en route. Upon their return, a syndicated article from April 1938, dateline Hollywood, put an entirely different spin on the trip:

Ione has just returned from the thrill trip of a lifetime — an expedition into the steaming Panama jungles. She was chosen to accompany the scientific party headed by George Palmer Putnam, husband of Amelia Earhart, because danger is a business with Ione. Palmer [sic], whose party cruised to Central America aboard Tay Garnett's yacht Athene, selected Miss Reed as a member of the group making the trip because he felt her courage would be an asset in filming motion pictures in the jungle. Reed is quoted as saying she rode a "20-foot-long sea elephant" and wrestled a boa constrictor on the trip before the party proceeded up river more than 100 miles in native canoes.[10] Any attempts at discretion by the new couple were for naught. Both being celebrities in their own right, Ed Sullivan reported at the top of his syndicated Hollywood gossip column of July 2, 1938: "Amelia Earhart's husband, George Palmer Putnam, and Iona Reed [sic], cinema stunter, are a combination."[11] Another Other Woman Rarely did Putnam miss an opportunity to turn an adventure into a book deal. Back in the States in 1938 he formed a separate boutique publishing firm, George Palmer Putnam Inc.,[12] at 6253 Hollywood Boulevard. In early 1940 it published "Stunt Girl," a romance novel coauthored by Rose Gordon and Ione Reed, written around Reed's experiences as a stuntwoman.[13] By that time, Reed was no longer part of Putnam's personal life. Lovell continues in her Earhart biography:

[E]ventually it seems George found her company irritating and drove her off in a somewhat cruel manner by deliberately provoking arguments and constantly finding fault.[14]

This characterization is sourced to 1941 correspondence between Janet Mabie and Amelia's mother, Amelia "Amy" Otis Earhart, whose observations are tainted because both harbored grudges against Putnam. Mabie was the ghostwriter of Putnam's 1939 book about Amelia, "Soaring Wings," for which Putnam failed to credit her as agreed; while Amy, who never liked him, believed Putnam had gone to court for access to Amelia's meager funds too soon — before Amy was ready to accept that her daughter wasn't coming back. For several preceding years, Amy had relied on Amelia for a regular monthly check.[15] There is another, simpler explanation for Putnam and Reed's estrangement. In the fall of 1938, Putnam met and was smitten by Jean-Marie Cosigny James, a Beverly Hills socialite who was in the process of divorcing her attorney husband. Earhart was declared legally dead in January 1939, Jean-Marie's divorce was final in May, and Putnam married her three days later. Putnam rented out his Los Angeles home to actor Eddie Albert (he needed the money), and the new couple moved to a mountain cabin above Lone Pine. Then came Pearl Harbor. Putnam enlisted in the Army Air Force and served as an intelligence officer. When he came home on leave, Jean-Marie filed for divorce — a move she later regretted. One gets the sense that having a husband who decides to go off to war at age 55 wasn't the type of marriage Jean-Marie signed up for. Depressed, Putnam returned to service and used the opportunity to chase rumors of Earhart sightings on Saipan. "His feelings were never shallow, not for any of his wives," Jean-Marie said in a 1988 interview. "He couldn't stand not being married, not having a companion. He needed that background in his very busy life."[16] He would marry once more before his death in 1950. So, who was Ione Reed? A Starlet is Born Ione Novelle Reed entered the world February 11, 1903, in the hamlet of Cade (now Cade Chapel), outside of Wortham, Texas. She achieved notice as a pianist at nearby Frost High School where she graduated in 1920. She drove out to Hollywood in 1924 with her mother, Lucy Jane, and her brother, Kenneth. They rented a bungalow near the Fox Studio at Western Avenue and Sunset Boulevard where Kenneth's riding ability landed him a part in a Western drama.[17] Ione reportedly walked onto the set and into the Fox picture, "The Blizzard" (1924). Ione's career would take off, but Kenneth's evidently did not.[18] That same year, Ione caught a break when she caught the eye of judges of a swimsuit competition at Balboa Island, Newport Beach.[19] Selected entrants got a screen test from American Vitagraph Co. Rival studios were always on the lookout for fresh talent to pit against Mack Sennett's Bathing Beauties at Pathé Exchange.

Piecing together Reed's biography is challenging because popular anthologies offer cursory and conflicting data.[20] What we can surmise from all sources is that Fox must not have signed her to a contract. It's possible Reed spent quite a bit of time in the Santa Clarita Valley in 1925, because she was cast as the female lead (often opposite Al Hoxie) in several Westerns directed by J.P. McGowan and released by W. Ray Johnston's Rayart Pictures. McGowan and Johnston were already using the SCV for outdoor locations in the mid-20s. It's hard to know, though, because the 1925 films are "lost," as are 75 percent of all films from the silent era.[21] Sources agree Reed played the female lead opposite Pete Morrison in a pair of 1926 Westerns called "Chasing Trouble" and "Bucking the Truth" for Carl Laemmle at Universal.[22] She starred opposite Hoxie in a 12-chapter serial in 1926-27 and had other leading roles through 1930 when she costarred in a pair of Bob Steele vehicles, "The Man from Nowhere" and "Western Honor." The latter were directed by McGowan, distributed by Johnston and Trem Carr's Syndicate Pictures, and were almost certainly filmed in the Santa Clarita Valley.[23] At the time, Reed was rooming at the Patrician Apartments at 1835 Wilcox Ave., off of Franklin Avenue in Hollywood.[24] The building still stands (2018). A Sidestep to Sound

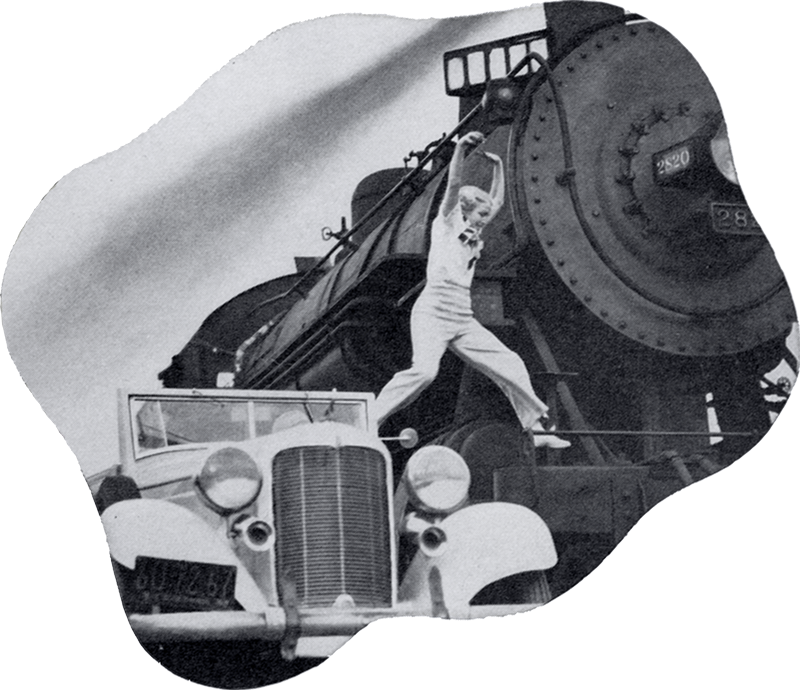

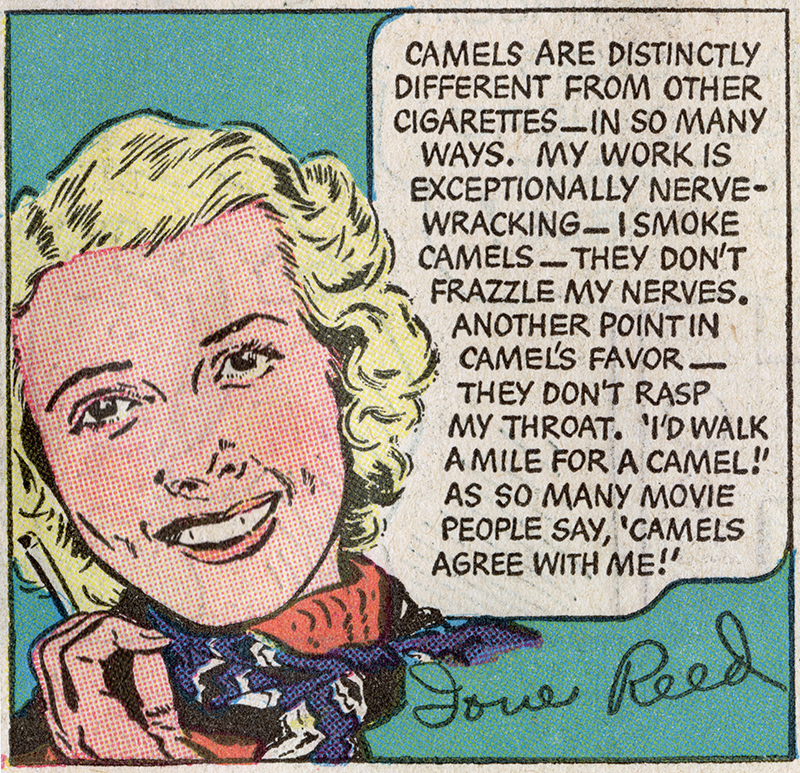

The Bob Steele features were her last starring roles. Stunts were performed by Cliff Lyons (1901-1974), whom Reed had gotten to know well from working together on earlier McGowan pictures. At some point their relationship became more than professional.[25] Lyons would have a heavy influence on her next career move. As the 1930s dawned, Reed wasn't quite the 21-year-old bathing beauty who could pass for 18. She had matured into a handsome woman. Moreover, it was the beginning of "talkies," and she spoke with a sweet Texas twang.[26] (Click here to hear her.) Reed transitioned into stunt work, and by all accounts, she was good at it. Her specialties were auto-to-train transfers and runaway buckboard stunts,[27] although she also worked with lions, bears and elephants.[28] Stunt work was uncredited back then, so a complete list is lacking. But we know she doubled Claire Trevor (of later "Stagecoach" fame) in 1934's "Elinor Norton." Reed looked a lot like Trevor, seven years her younger. Even without screen credits, Reed must have been sufficiently well known to the public for her stunt work in the 1930s, because R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. saw fit to capitalize on her celebrity by using her name and likeness in an ad campaign for Camel cigarettes. The advertisements identified her not as "actress" but as "movie stunt girl." The ads suggested Camels relaxed her after a round of life-threatening escapades.[29] (Although Amelia Earhart once endorsed Lucky Strike cigarettes, the aviatrix was a non-smoker[30] — as well as a teetotaler.)

In 1935, Reed had a minor on-screen role in a Gene Autry picture, "Melody Trail" (filmed in San Bernardino), followed in 1936 with more Claire Trevor vehicles, "My Marriage" and "Song and Dance Man." Her next known work was on "The Buccaneer" with Fredric March. The film premiered in January 1938, but shooting took place from August-October 1937, before Reed left on her South Seas adventure with George Putnam. Her biggest picture from a production standpoint was 1939's "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" when she doubled Maureen O'Hara. After that, there was just one more known credit when she played a bit part as a nurse in the war picture, "First Yank Into Tokyo," released September 5, 1945, three days after Japan's formal surrender. By that time, Reed had given up acting because, she said, a doctor had diagnosed her with an allergy to makeup. Safety First Or was it all those years of hair coloring? She's a brunette in a photograph that accompanies a syndicated 1945 news article about her. It wouldn't have been atypical for her to have dyed her hair blonde when she was trying to break into pictures in the 1920s. But that's speculation. "When my doctor told me back in 1941 I couldn't use makeup for a year, my sister bet me there wasn't anything else I could do to earn a living," Reed recalled. "The next week when I heard that a radio plant was hiring people for 35 cents an hour, I applied and was given a job as a hot tinner"[31] (a soldering job). She went to work as the safety supervisor for Brooklyn-based Lewyt Corp., which had started out making vacuum cleaners but transitioned to military equipment during the war. "It takes split-second timing to dodge in and out of heavy traffic, race a car across the path of a train and fall head-first down a steel flight of steps, and this same sense of timing, which I have learned through acrobatic dancing, has helped me no end in my safety work at the plant," she said in a 1945 interview.[32] A member of the American Society of Safety Engineers, Reed didn't stray from her roots while at Lewyt. In addition to inventing new safety protocols, she was in charge of entertainment. She managed an annual musical stage production featuring company employees, which was used as a benefit for the troops.[33] How she ended up in New York in 1945 is unknown, but she must have stopped home in Texas after the war because she brought something — or rather someone — back to Los Angeles with her. In 1935, Ione had been living in a single-family home she owned at 12208 Riverside Drive in North Hollywood. (It is now an apartment building.) At the time, her mother, Lucy Jane Reed, a seamstress in a retail drapery store, was living with her. They were still there in 1940.[34] Evidently, Ione held onto the house during war, because she was back in it in 1948 — only now she was Mrs. Ione R. Goodwin, wife of Garrie Lathum Goodwin, a Texas oil man two months her junior.[35] Next, sometime between 1954 and 1956, the Goodwins moved to 10223 Variel Avenue in Chatsworth (now condominiums).[36] Garrie Goodwin died March 6, 1966. His last known address was in Newhall.[37] For now, we don't know whether Ione lived with him in Newhall. We do know she eventually moved back to Texas. She was 82 when she died in Dallas on August 11, 1985.[38] Was it Ione's derring-do that was attractive to George Palmer Putnam in 1938? Did she fit a type? Or was her personality too much of a reminder of Earhart's adventurous spirit? We can only guess. —Leon Worden 2018 Genealogical and additional research assistance by Tricia Lemon Putnam (no relation).

1. Putnam, George Palmer. "Soaring Wings: A Biography of Amelia Earhart." New York: Harcourt Brace, 1939; Manor Books 1972 edition, pg. 234-236. 2. Lovell, Mary S. "The Sound of Wings: The Life of Amelia Earhart." New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1989. Introduction. 3. Putnam, op. cit: 91. 4. Lovell, op. cit.: 105. Didn't like to fly: pg. 135. Also Putnam, op. cit, pg. 230: "I am subject to the most convincing seizures of air sickness." 5. Lovell paints a softer picture of Earhart's separation from Sam Chapman (pg. 138 ff.). By November 23, 1928, when Earhart publicly announced she had terminated the 5-year engagement, their lives had already grown apart. Chapman would remain a dear friend. It was a different story in the Putnam household. By the summer of 1929, George's romantic entanglement was undeniable to his wife of nearly 20 years, Dorothy Binney Putnam, who packed her bags and walked out on him — while Earhart was at the house for a "celebrity-studded outdoors barbecue" (pp. 152-153). Dorothy soon remarried (pg. 157). 6. Ibid: 165. Lovell says Earhart wasn't head-over-heels in love with Putnam when they married, but within a fairly short time, her love for him blossomed. That said, the couple spent much time apart, and there were persistent rumors (about Earhart). 7. Ibid.: 203. Despite appearances (and sloppy news reporting), Putnam was no millionaire. Just prior to the 1929 stock market crash, the patriarch of G.P. Putnam's Sons died, and his heir, a cousin to George, drove the company in to the ground. George never recovered his investment. He actually needed the income from Paramount and subsequent ventures (he left Paramount around 1934). He, along with "angel donors" such as J.K. Lilley (of Eli Lilley) and Vincent Bendix, helped finance Earhart's various airplanes and work expenses (pg. 226 ff.). In December 1938, George had to sell his house to remain solvent (pg. 304). See note 30. 8. Ibid.: 300. 9. "Putnam Sails for South Seas," Los Angeles Times, December 17, 1937, cover of Part II: City News. 10. "Stunt Girl Thinks Job is Prosaic" by Alexander Kahn, as published in the Pittsburgh Press, April 29, 1938. 11. "Hollywood" by Ed Sullivan, as published in the New York Daily News, July 4, 1938. 12. Lovell, op. cit: 301. 13. "Stunt Girl Heroine," Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1940. 14. Lovell, op. cit: 300. 15. Ibid.: 193. Uncredited ghostwriter: pg. 305. Amy's resentment: pp. 302-303 ff. Meager funds: The gross value of Amelia's estate was $59,108. Debts and expenses, including Amy's upkeep, came to $45,329, leaving a net distribution of $13,779 (pg. 304). 16. Ibid.: 308. Regret: pg. 320. 17. "Graduate of Frost High School Will Be Elevated to Stardom," The Corsicana (Texas) Daily Sun, January 13, 1930. 18. "Movie Stunt Girl Visits Brother Here," Dallas Morning News, November 11, 1938. The article announces Ione's visit to her brother Kenneth at his home in Dallas. 19. "Screen Chance to be Prize Offered Winner of Parade of Bathing Girls at Balboa," Santa Ana Daily Register, April 25, 1925. Reed was a winner the previous year. 20. Further, her name does not appear at all in places where one might expect to encounter it at least in passing, such as the multi-volume "History of the American Cinema" series from University of California Press; the autobiography of Yakima Canutt (with whom she worked); the biography of J.P. McGowan (with whom she worked); or the story of Mascot Pictures (many of whose players intersect with Reed's career); much less the autobiography of William S. Hart (which was published in 1929 and whose retirement from the screen coincided with her start in pictures) or the 1939 Amelia Earhart biography by George Palmer Putnam (who had no reason to include her and every reason not to). She doesn't even get a mention in Mollie Gregory's "Stuntwomen: The Untold Hollywood Story" (University Press of Kentucky, 2015). 21. Patrick Loughney, Director, The PHI Stoa (The Packard Humanities Institute, Santa Clarita facility); previously chief of the Library of Congress' National Audio-Visual Conservation Center. Personal conversation, September 18, 2018: Nothing remains of 75-76 percent of all motion pictures made between 1913 and 1930. 22. Katchmer, George A. "A Biographical Dictionary of Silent Film Western Actors and Actresses." Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company Inc., 2002. The entry for Ione Reed (pg. 318) is remarkably incomplete. 23. "The Man from Nowhere" and "Western Honor" are presumed to be lost films. Johnston and Carr's Syndicate Pictures primarily filmed in Placerita Canyon. They would soon reorganize Syndicate into the first iteration of Monogram Pictures Corp. McGowan was using the Santa Clarita Valley extensively during this period. The cast and crew include additional members who routinely appear in the credits of locally made films. 24. 1930 U.S. Census, enumerated April 18. Ione Reed roomed with Ian Francis J. Reed, age 50, and his wife Marjorie G. Reed. We don't know her relationship to the couple, if any. Ian Reed emigrated from England in 1910; Marjorie was born in New York. Ione's parents were from Texas and Mississippi. Other motion picture professionals lived in the same building. Also: The Corsicana (Texas) Daily Sun, op. cit., mentions her address. 25. "Beth Marion" by Boyd Magers. Blog post on WesternClippings.com (accessed September 2018). A B-Western heroine in the 1930s, Marion quit the business in 1938 when she married Cliff Lyons. Magers quotes her: "I met Cliff in Lone Pine when Ione Reed was his girlfriend. They were having a big fight then, and she was going on about him. So I knew all about him from her. We all ate together one night in the dining room at the Dow Hotel. That was all [emphasis in the original]. I just met him. At least six months later, he called. ... He said he had straightened up all of his affairs because he had decided to marry me." 26. Freese, Gene Scott. "Hollywood Stunt Performers, 1910s-1970s: A Biographical Dictionary," Second Edition. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company Inc., 2014. Note: The vital statistics for Reed do not match other sources and do not fit known facts. Unfortunately, the erroneous information in this work has been widely replicated on the Internet. 27. "Ione Reed." Episode of "The Daredevils of Hollywood" radio program hosted by Hanley Stafford, aired May 23, 1938, on CBC (CJRC, Winnipeg) and NBC-Blue (KERN, Bakersfield). The subject speaks on the program. 28. "Three Seconds from Death," Popular Mechanics Magazine, November 1938. 29. For example, a 4-color comic strip, at least two different full-page Life magazine ads (one) and (two), and newspaper advertisements like this one in the Valley Evening Monitor, McAllen, Texas, July 25, 1938. 30. Putnam, op. cit: 192. While this is generally true, it is part of the Earhart legend that Putnam created during and after her lifetime. An early news article that was published soon after their initial meeting, a week prior to her first transatlantic flight, offers a slightly different take on her tobacco use: "She smokes a little but does not care particularly about it" (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 10, 1928). The subsequent Lucky Strike endorsement was to help raise funds ($1,500) for Admiral Byrd's Antarctic expedition. It was customary for adventurers such as Earhart, Byrd, Lindbergh and Martin Johnson to fundraise from friends and associates (Putnam, pg. 197). Theirs were costly endeavors. Earhart subsisted largely on her income from the lecture circuit ($250 per, in the 1930s) and from lecturing at Purdue University. 31. "Stunt Girl Now Teaches Safety to War Workers" by Rosellen Callahan, as published with a photograph and a Brooklyn dateline in the Shamokin (Penn.) News-Dispatch, June 19, 1945. 32. Ibid. 33. "Lewyt '45 Show April 22," The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 15, 1945. 34. 1940 U.S. Census, enumerated April 2. 35. Index to Register of Voters, Los Angeles County, 1948. Texas oilman: Selective Service Registration Card, Garrie Lathum Goodwin, February 16, 1942. 36. Index to Register of Voters, Los Angeles County, 1950, 1954 and 1956. 37. Social Security Administration. Social Security Death Index, Master File. Social Security Administration. Ione's mother, Lucy, died July 4, 1961, in Ventura County. Although Ione is buried in Dallas, both her mother and her husband are buried in Forest Lawn-Hollywood Hills, albeit in different sections. 38. Ibid.

Hart and Earhart. Legend has it that Amelia Earhart used to land at the Newhall Intermediate Field, aka Saugus Airport, in the 1930s. Everybody did; it was a popular landing strip for light aircraft in the 1930s and '40s. At least we know one of her planes landed there. It's how she ended up meeting William S. Hart. "Paul Mantz [Earhart's business partner and mechanic] had borrowed AE's Lockheed Vega one day," Earhart's widower wrote in 1939, "and in the course of a landing at the Newhall field had flown lower than he should over Bill's home." The writer, George Palmer Putnam, continues:

"Damn near shook the bricks out of the chimney," Bill sputtered later. He roared out of the house and got the number of the plane — NC965Y — which he promptly communicated to the sheriff. In due time the complaint caught up, via the local Department of Commerce inspectors, with the plane and pilot. "Before the trouble was straightened out," AE used to tell the story, "the plane's owner, being myself, went with the offending pilot to call on Bill. Paul to square himself, I because I wished to meet a man who liked to live on a hilltop and didn't want to be disturbed — both admirable ambitions."[1] Hart was "among [the] friends in California whom AE liked most," Putnam writes, and the sentiment was clearly mutual. Columinst Hedda Hopper wrote in 1941 that Hart counted a photograph of himself with Earhart, and a small American flag she gave him, as his most prized possessions.[2] "We'd sit on the porch while the evening shadows lengthened and little rabbits stole out of the brush romping noiselessly across the green lawn," Putnam writes. One of Hart's Great Danes "persisted in giving fruitless chase to the moon-struck bunnies." Describing Hart's Horseshoe Ranch as a "treasure-house of relics of its owner's bright yesterdays," Putnam remembers: "One of the last evenings AE and I spent there, Bill ran off for us a couple of his silent pictures — 'Tumbleweed' [sic] and one other. ... 'Amelia,' he said when the lights went up, 'I never made a bad picture.' She said she was sure of that."[3] In October 1936, Hart mailed Earhart a letter in which he said he was sending her a buffalo coat that had been used by the U.S. Army during the Indian Wars of the 1870s. She hadn't acknowledged the gift by February 1937 when Hart mailed her another letter, asking whether it fit. It's unlikely she ever acknowledged it. The following month, March 1937, she made her first aborted attempt at a circumnavigational flight of the globe; in June she took off for her second and last attempt.

We know she received the coat, because in early 1937 she gave it to a friend for safekeeping. At the time, Earhart and Putnam were staying on a friend's dude ranch in the foothills of Wyoming's Absaroka Mountains. The friend, Carl M. Dunrud (1891-1976), was building them a small log cabin near his Double Dee Ranch in Meeteetse. They had commissioned the cabin while vacationing with Dunrud in 1934.[4] In 1937, Earhart gave Dunrud a number of items she evidently intended to use later. Among them were the buffalo coat Bill Hart gave her and the leather jacket she wore on several of her historic flights. But there was no "later." When he got the news July 3, 1937, Dunrud stopped work on the cabin. Dial up the clock 30 years. One day, Dunrud walked into the Buffalo Bill Historical Center (now the Buffalo Bill Center of the West) in Cody, Wyoming, and handed over the items Earhart had given him to a close friend, Harold McCracken, the museum director. Among them were the flight jacket and the buffalo jacket from Bill Hart[5] — who, coincidentally, had been invited to the opening of the museum back in 1927. (Hart was in Montana at the time, but it's unknown, for now, if he got there.) More years passed, and somehow or another, the buffalo jacket was misidentified as having belonged to Buffalo Bill. John Rumm, the museum's curator from about 2008-2015, previously with the Smithsonian Institution, corrected the error.[6] There is at least one other item Bill Hart gave to the famous aviatrix. It is a copy of his 1929 autobiography, "My Life East and West," which he inscribed to "a great American, Miss Amelia Erhart," her surname misspelled. The inscription is dated 1936. We don't know, but it's possible he sent it with the coat. We do know she received it, because it's got her bookplate in it: "From the Library of Amelia Earhart." At some point fairly early after her disappearance, it ended up in the library of Miles Standish Slocum, a prominent Pasadena book collector who focused on the literature and history of the American West. After Slocum's death in 1956, it passed down eventually to his granddaughter.[7] In August 2018, by way of the granddaughter's nephew, Bryan Woodhall of Custer, South Dakota, the book came home to Newhall where it started.

1. Putnam, George Palmer. "Soaring Wings: A Biography of Amelia Earhart." New York: Harcourt Brace, 1939; Manor Books 1972 edition, pp. 234-236. 2. As published in The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise, April 4, 1941. 3. Putnam, ibid. 4. Lovell, Mary S. "The Sound of Wings: The Life of Amelia Earhart." New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1989, pp. 204-205. 5. Rumm, John. "Her Plane Vanished. Her Flight Jacket Didn't." Blog post, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, March 17, 2014. 6. Baskas, Harriet. "The Surprising Home of Amelia Earhart's Flight Jacket." Blog post, Stuck at the Airport, September 30, 2013. 7. Bryan Woodhall, personal communication, August 2018.

LW3410: 9600 dpi jpeg from original photograph purchased 2018 by Leon Worden.

|

Honored by Sioux 1926

Little Bighorn Anniversary 1926 x2

Dam Disaster 1928

With Charlie Mack in Newhall 1930s

With Wallace Beery, Moran & Mack in Newhall 1930s

With Lina Basquette 1932

Real Estate Instructions 1932

Watson Photo

1920s-1930s

At Saugus Rodeo 1933

Letter to M. Perkins 1933

With Freddie Bartholomew 1935

"Smiling" Bill Hart 1936

LA Times Feature 1936

Letter: Gift of Buffalo Coat to Rudy Vallee 1936

Letter: Gift of Buffalo Coat to Amelia Earhart 1936

Brown Derby 1938

Hart, Ione Reed, George Putnam 1938

With Andy Jauregui 1938

Guns on Radio 1941

Robert Taylor Photo Shoot 1941: BTK Gun, Fritz's Grave (Mult.)

With Dan White ~1945

With Horses 1940s

At Home 1-7-1946

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.