|

|

|

Tataviam plain-twined twined basketry fragment with coating of asphaltum, from lower Piru Creek area. Juncus wefts; warps unknown (probably juncus). L.A. County Natural History Museum (NHMLA) collection, on display (in 2018) at the La Brea Tar Pits Museum in Los Angeles. Photographed through plexi case with various camera settings. Shanks and Shanks (2010) reference this fragment in their discussion of this twined water bottle at pg. 56: "In the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County there are archaeological basketry specimens collected by Richard Van Valkenburgh from Piru Creek in Tataviam territory. The most complete twined basket is a distinctive low, broad bottleneck-shaped water bottle [which] is unlike neighboring Chumash or Gabrielino/Tongva water bottles and almost certainly is Tataviam." Could this fragment be the missing piece of the water bottle? Van Valkenburgh explored and recovered artifacts from several caves in the Piru Creek drainage area from 1932-1936 on behalf of NHMLA; see Lopez (1974).

About Tataviam Basketry. When it comes to Native American basketry — woven bowls, baskets, trays, water bottles, etc. — none is rarer than basketry made by Tataviam people of the Santa Clarita Valley. As of 2018, no basketry from any era can be irrefutably attributed to a specific Tataviam individual (known by name). The closest we come is Sinforosa Fustero, the last Tataviam weaver (and speaker), who died either in 1912 or 1915, depending on the source. Three baskets in the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society collection are sourced to Sinforosa; two of them she might have collected but did not make (one from the Lake Tahoe area, the other from Arizona), and the third is of uncertain origin. It's possible she made it. A small number of baskets, perhaps a few dozen, in private and public collections were made by known and unknown weavers in bordering areas where Tataviam individuals lived alongside people from other indigenous cultural and linguistic backgrounds (San Fernando Valley, Fillmore-Santa Paula, Tejon). The known-by-name weavers weren't Tataviam, and no unattributed basket from the borderland is recognized as distinctively Tataviam. As of 2018, all 100-percent certified Tataviam basketry is archaeological, and all was made prior to the end of the Spanish Mission period in the 1820s. By "all" we mean a dozen specimens. Twelve. Twelve for-sure Tataviam basketry items are known today. (We repeat "as of 2018" because new discoveries continue to be made.) The "Tataviam Twelve" are: * The nine storage baskets, bowls, hoppers and trays in the Peabody Museum at Harvard University. They were found by boy ranchers in 1884 in a small cache cave high up a mountainside near present-day Val Verde. They were purchased shortly thereafter by Stephen Bowers, who was collecting native California cultural materials for the Peabody. The materials, including sacred ceremonial items, were secreted in the cave — with the intent of later recovery (never effected) — most likely in 1802 or 1811, the years in which Spanish soldiers raided the local Tataviam villages and brought their inhabitants to the San Fernando Mission. Today the cave, known as Bowers Cave, is on the grounds of the Chiquita Canyon Landfill. It is not covered in garbage and probably never will be, considering its elevation. The cave has been excavated several times and is devoid of any cultural materials. All "Bowers Cave" basketry is coiled with a juncus weft on a deergrass bundle foundation (Muhlenbergia rigens), although three specimens alternate a deergrass foundation with a 3-rod juncus foundation, which is typically a Chumash characteristic. Two basketry items additionally use sumac (Rhus trilobata) as a weft material. The coiling direction is to the right, and the fag ends (the starting end of the weft stitch) are bound under. Rims are self-rims (or missing) except for one specimen with some plain wrapping. Only one basket has any decoration; it is encircled by "block-step" designs that are visible on the interior and exterior and are made of (mud-)dyed juncus. These are important diagnostic markers which are perhaps more helpful in identifying what isn't Tataviam than what is, because, other than the occasional 3-rod foundation, these traits are common to almost all basketry from the so-called "mission" region that stretches from the Santa Clarita Valley-southern Antelope Valley, on the north, to northern Baja, Mexico, on the south. Thus, the corollary: If it's a coiled basket and it doesn't have these characteristics, then it's not Tataviam. Then again, if it's a juncus basket with bound-under fag ends on a 3-rod foundation, it's highly likely to be Tataviam. (Please contact us immediately if you find such a thing.) As for the form and function of the storage baskets, bowls, trays and hoppers, they're not distinctive. The shapes and uses are fairly standard throughout the Southwest. * This twined water bottle from Piru Creek, which resides in the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum. Collected by Richard F. Van Valkenburgh in the 1930s, it is diagonally twined (up to the right) with juncus wefts on juncus warps, coated in asphaltum (local tar) for waterproofing. * A plain-twined basketry fragment from Piru Canyon, with an asphaltum coating, in the L.A. County Natural History Museum collection. Possibly also collected by Van Valkenburgh in the 1930s. On display at the La Brea Tar Pits Museum. * This 7-inch-diameter coiled basketry fragment found in the 1970s in a rock shelter (small cave-like feature) at Vasquez Rocks. Round and flat, it was probably the base to a long-disintegrated storage basket. (Vegetal material doesn't survive outside of caves, and sometimes not even then.) Like the Bowers Cave material, it coils to the right with juncus wefts on a deergrass foundation and bound-under fag ends. Privately owned by Roger Basham, retired chair of the Anthropology Department at College of the Canyons, as of 2019 it is in the process of being transfered to the L.A. County Department of Parks and Recreation for safekeeping and display in the Interpretive Center at Vasquez Rocks — from whence it came.

LW3494: Download original images here. Digital images by Leon Worden, April 18, 2018.

|

Bowers Cave Specimens (Mult.)

Bowers on Bowers Cave 1885

Stephen Bowers Bio

Bowers Cave: Perforated Stones (Henshaw 1887)

Bowers Cave: Van Valkenburgh 1952

• Bowers Cave Inventory (Elsasser & Heizer 1963)

Tony Newhall 1984

• Chiquita Landfill Expansion DEIR 2014: Bowers Cave Discussion

Vasquez Rock Art x8

Ethnobotany of Vasquez, Placerita (Brewer 2014)

Bowl x5

Basketry Fragment

Blum Ranch (Mult.)

Little Rock Creek

Grinding Stone, Chaguayanga

Fish Canyon Bedrock Mortars & Cupules x3

2 Steatite Bowls, Hydraulic Research 1968

Steatite Cup, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x5

Ceremonial Bar, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x4

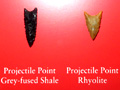

Projectile Points (4), 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig

Paradise Ranch Earth Oven

Twined Water Bottle x14

Twined Basketry Fragment

Grinding Stones, Camulos

Arrow Straightener

Pestle

Basketry x2

Coiled Basket 1875

Riverpark, aka River Village (Mult.)

Riverpark Artifact Conveyance

Tesoro (San Francisquito) Bedrock Mortar

Mojave Desert: Burham Canyon Pictographs

Leona Valley Site (Disturbed 2001)

2 Baskets

So. Cal. Basket

Biface, Haskell Canyon

2 Mortars, 2 Pestles, Bouquet Canyon

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.