|

|

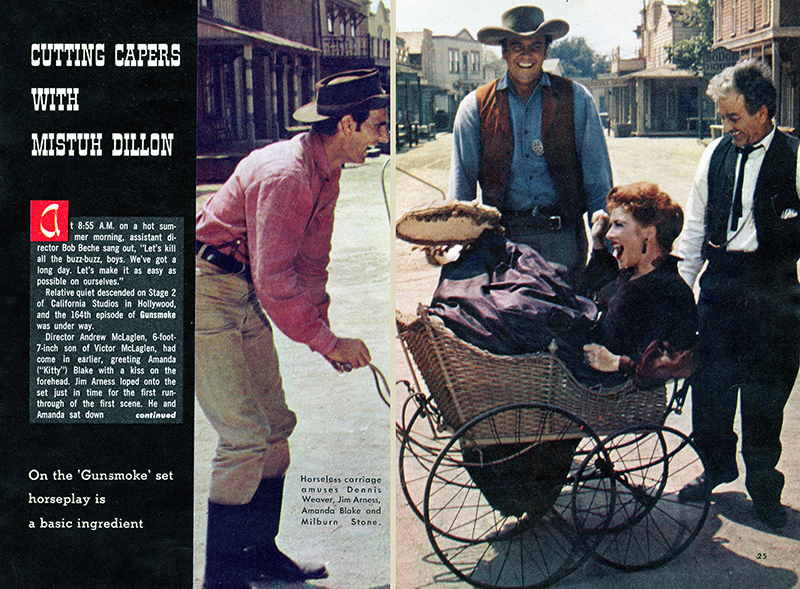

Cutting Capers With Mistuh Dillon.

On the "Gunsmoke" set, horseplay is a basic ingredient.

TV Guide | September 12, 1959.

|

Webmaster's note.

The action in the story below takes place on a sound stage in Hollywood. The action in the photo takes place at Gene Autry's Melody Ranch movie town in Placerita Canyon.

At 8:55 a.m. on a hot summer morning, assistant director Bob Beche sang out, "Let's kill all the buzz-buzz, boys. We've got a long day. Let's make it as easy as possible on ourselves." Relative quiet descended on Stage 2 of California Studios in Hollywood, and the 164th episode of "Gunsmoke" was under way. Director Andrew McLaglen, 6-foot-7-inch son of Victor McLaglen, had come in earlier, greeting Amanda ("Kitty") Blake with a kiss on the forehead. Jim Arness loped onto the set just in time for the first run-through of the first scene. He and Amanda sat down at a table in Kitty's Long Branch saloon, scripts in front of them. Because they are so familiar with the characters they play, the show's four regulars don't bother to learn their lines as written. They read a script to get the feel of it, then read it through again at a weekly Monday conference, with the director and producer sitting in. The actors change the lines — a word here, a phrase there — to be more "comfortable." When the director calls for the first "take," they have the dialog down pat. The early-morning run-throughs, when everybody is fresh, are occasionally enlivened by quiet horseplay. In the initial scene this particular morning, a "Big Daddy" sort of character has caught his errant son swilling whisky in the saloon and is running him out of the place, intent on lambasting him out on the street. Marshal Dillon rises and follows them. * * * As Arness rose from his chair on the first run-through, Amanda put her hand on his arm and ad-libbed solemnly, "Matt, be careful." "No," said McLaglen, painfully recalling the dialog from a Maverick parody of "Gunsmoke," "I wouldn't say that if I were you." "Oh, well," Amanda said. "It was just a happy thought." Arness, grimacing and fussing over his script, suddenly came to a line that appealed to him. "Hey," he said, poking Amanda, "I can get a lot of sex appeal into this line." "I can't stand it," she groaned. "All right, boys," McLaglen called out, "let's go. Let's fade in on Matt." "This will be a picture," Beche shouted. "Lose all your watches, duck your cigarets, beer 'em up. Let's go." The scene, involving numerous cues, went off without a hitch on the first take. "Cut and print it," McLaglen shouted. The actors broke for cool spots inside the cavernous studio. Arness sprawled out awkwardly on a cot in the small portable dressing room on the set, his knees pulled up, his big hat resting on his chest. "I've got a good deal," he said. "I had a five-year contract with CBS, but we broke it off at four and wrote a new one. Now I own a chunk of the show and I'm setting up my own production company. We'll continue with 'Gunsmoke,' maybe even to a seventh season. We'll also create and develop a couple of series." * * * Arness had recently made the jump from actor to company president, and the effects were showing. The 'Gunsmoke' cast and crew were giving him the needle, addressing him as "Mr. President" and asking permission to speak. Later in the day, when he stood alone in the middle of the long indoor Western street reading a line, the crew broke into a calculated storm of wry applause. Arness swept his hat off and bowed low, grinning amiably. It was a slow day and a rather dull one. The smell of fresh straw and three horses lay heavily in the atmosphere. Desultory gin-rummy games continued from morning until night. On other days, in other seasons, the "action" on the set had been a bit livelier. There was the time, during a tense scene, that Arness, as Dillon, handed a note to Dennis Weaver, as Chester, with the order to "Read this." Weaver took a look at the note and exploded with laughter, destroying what would have been a perfect "take." What Arness had done was to scribble something unprintable across the paper. Weaver got his revenge not long after. With the help of some of the crew he jacked up Arness' sports car so that the rear wheels were an inch off the ground. Arness, not noticing, jumped into the car to head home after the day's shooting. The wheels spun, the car stood still and Arness — for a horrified moment — envisioned an astronomical repair bill for a new transmission. On this summer day, the regulars had little to do but walk through their parts. The acting chores fell to "Big Daddy" Peter Whitney and Richard Rust, playing his son. Whitney was to beat Rust with a thick leather belt — actually a piece of soft felt. McLaglen carefully mapped out each swing of Whitney's arm and each resulting twist of Rust's body. They walked through the action, slowly, several times. After two false starts before the camera, they got into the swing of it. McLaglen nodded approval, then said, "Cut and print it." * * * In his upstairs dressing room, Milburn Stone — Doc — stretched out on a bed. "I'd be just as happy to see this show go on for the next 10 years," he said. "I love this character of Doc. There are any number of character actors who could play the part just as well as I do and even better, but I don't think anybody understands Doc as well as I do. "Actually, he's pretty much based on my own grandfather, who came from Kansas and lived right around the time this show is played, around the 1870s. The stooped walk is his, and so is the brevity of his speech. "We're a pretty comfortable group on this set. After all, we've been working together almost five years now. We all know one another pretty well, but we don't see much of each other away from work." Knowing each other pretty well can provide opportunities for memorable pranks. Once "Gunsmoke" producer Norman Macdonnell was summoned to the set by an assistant director. "We've got trouble — it's Milburn Stone," Macdonnell was told, as he hurried down from his office. He found the crew standing by, ashen-faced, while at the far end of the Dodge City street Stone and director John Rich were arguing bitterly. Macdonnell clapped his hand to his head, visualizing the whole show falling apart. Just as Stone and Rich were reaching the swinging point, they turned to the perspiring Macdonnell and sang "Happy Birthday." Stone — recalling the occasion — chortled and walked downstairs. * * * Down on the set, Amanda had partially unzipped her long, tight Western gown to let the studio air play across her back. Dennis Weaver sat in a canvas chair beside McLaglen and quietly went over the next scene. McLaglen, normally a mild-mannered man with the gait of a large sleepwalker, was getting a little edgy He had been through a 20-minute discussion with Arness on how one short scene should be played and had to bow, finally, to the stubborn insistence of the company president. "Big Jim sort of loused that one up," an observer noted, "but I'll bet you 2-to-1 that Andy gets it right back the way he wanted it, once it's in the cutting room. Jim's really a very decent guy," he added, almost defensively. "He's just feeling his oats." Production No. 164 was wrapped up by 6:30. The last scene involved Weaver and Stone, and the two pros waltzed through it effortlessly. "That's it," McLaglen said, pleasantly, if a little wearily. Another top-rater, they hoped, was in the can.

LW3541: TV Guide pages purchased 2019 by Leon Worden. Download individual pages here.

|

Legacy: James Arness

(SCVTV 2006)

Series Announcement 1955

James Arness 1950s

Prank Open 1955

Dennis Weaver, James Arness 1956

Dell No. 679 (Gunsmoke No. 1)

James Arness, Amanda Blake at Vasquez Rocks

TV Guide May 1957

Argosy Feature 1959

Jim Garner and "Gunsmog" 1959

Horseplay on the Set 1959

Memo: Use of Firearms 1974

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.