|

|

Coming Soon: "The Shepherd of the Hills."

LIFE Magazine | April 21, 1941.

|

Saugus rancher Harry Carey co-stars in the John Wayne vehicle, "The Shepherd of the Hills" (Paramount 1941), drawn from a 34-year-old novel by Harold Bell Wright.

Movies "Shepherd of the Hills" Filmed After 34 Years. The benign old man working at the card table below is writing his 18th novel. He is 70 years old. To a generation coming of age in a fearfully complex world his name brings, at best, a faint and amused smile of doubtful recognition. But to their parents he will be remembered as a landmark in an era now coated with the shimmer of nostalgia, a beautiful bygone day when peace and prosperity seemed like permanent and indestructible blessings. This old man is Harold Bell Wright. It was in 1908 that he first started on his strange and astonishing literary career. An itinerant sign painter turned preacher, he had written his first novel as a parable to be delivered in weekly installments from his pulpit. When published between covers, "That Printer of Udell's," to everyone's surprise, sold 500,000 copies. "The Shepherd of the Hills," four years later, rolled up a sensational sale of 2,000,000. Like other bestsellers of that happy decade (Gene Stratton Porter's "Freckles:" 2,000,000 copies; John Fox Jr.'s "Trail of the Lonesome Pine:" 1,255,-000), Harold Bell Wright's books were hearty, naive melodramas of the big out-of-doors whose chief virtue was that they brought to a heterogeneous people the beauty of the remote corners of their land. Otherwise, to modern concepts, these works seem almost bare of merits. The writing is lurid and overwrought. The characters are stalking cardboard figures, crudely symbolizing weakness or strength, courage or cowardice, good or evil, each brushed in solid with a single flat paint. The women are paragons of youth, health, beauty, charm and purity. The action goes galloping along, heedless of reality, from thrilling gun duel to breathless escape, from knock-down fist fight to hair-trigger rescue. But a generation of readers as yet unfamiliar with the austerities of a Hemingway, a Dos Passos or a Faulkner found such moral tales as "The Winning of Barbara Worth," "The Calling of Dan Matthews" and "The Re-creation of Brian Kent" so engrossing that, all in all, 10,000,000 copies of Wright's books were sold. Of his 17 novels, eight have been made into movies, some of them twice. The last, soon to be released by Paramount, is a Technicolor version of "The Shepherd of the Hills" (on opposite page), which, for all its mountain scenic splendor, has even in a restrained adaptation, the dated sentimentality of its 34-year-old book.

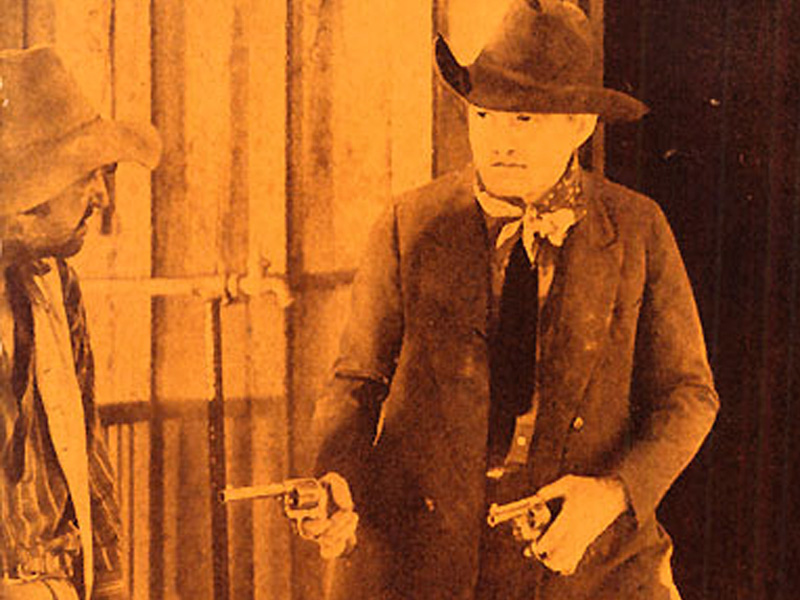

About "The Shepherd of the Hills." Saugus rancher Harry Carey portrays the title character in 1941's "The Shepherd of the Hills" from Paramount Pictures. Top billing went to John Wayne. It was his first Technicolor movie. Wayne (1907-1979) had caught the tail end of the silent period as an uncredited extra and graduated to leading roles in a series of black-and-white "B" (low-Budget) Western "talkies" that were filmed in Placerita Canyon in the early-mid 1930s. A generation ahead of him, Carey (1878-1947) was a big star as a middle-aged man during the silent period — maybe not as big as William S. Hart or Tom Mix, but a popular headliner nonetheless. He was one of the rare actors who transitioned smoothly from silents to sound (unlike Hart, who never did, and Mix, who did so awkwardly). The same year a young John Wayne got his break in "Stagecoach" (1939), audiences were reintroduced to a more mature and sagacious Harry Carey as president pro-tem of the Senate in "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington." It is this seasoned version of Harry Carey that cuts an imposing figure throughout "The Shepherd of the Hills:" patient when he needs to be, romantic at heart, yet strong and determined when the situation calls for it. It's hard to imagine better casting. Wayne later reminisced:

"[Carey] had a style that has now become the way of acting in our business. He tried to play it down a little and be kind of natural. You have to keep things going and try and get your personality through, which is what Harry could do. I loved him, because I'd known him for years, and I was a young man and he was an older man" (quoted in Eyman 2014:112). The film "provided Wayne's first opportunity to work with a boyhood idol," biographer Scott Eyman writes (ibid.), "and unlike Tom Mix, Harry Carey wasn't a disappointment.

"If John Ford ("Stagecoach") was the tough, demanding coach whose approval Wayne craved, Carey and his wife, Ollie, were surrogate parents who offered something approaching unconditional love. Their temperaments were well matched: Harry Carey was calm and good-humored, Ollie Carey was salty and plainspoken." (Author Eyman dedicates his John Wayne biography to their son, Harry Carey Jr.) "The Shepherd of the Hills" also introduced Wayne to director Henry Hathaway, who would influence his career. Hathaway directed Wayne in several more pictures over the next two decades, among them "The Sons of Katie Elder" (1965) and "True Grit" (1969). Principal shooting for "The Shepherd of the Hills" took place at Big Bear, and as usual, Duke Wayne found trouble — or rather, trouble found him, in the person of Marlene Dietrich (1901-1992). They had just co-starred in the aptly named "Seven Sinners," and "Wayne's co-workers knew they were having an affair," Eyman writes (pg. 110), "as did his friends (and) the FBI" — which had its eye on Dietrich because of some allegations she was a Nazi sympathizer — which she decidedly was not. In any event, this time, Olive Carey came to the rescue. Eyman provides the anecdote:

Trailing Wayne to the location at Big Bear was Dietrich, who stayed at Arrowhead, about twenty miles away. One morning a panicked Ward Bond sought out Harry Carey's wife, Ollie. Duke was missing, said Bond, and he didn't want to even think about what Hathaway would do to a star who failed to show up. Ollie Carey knew very well where Wayne was. She got in her car and headed for Arrowhead. Snow had fallen the night before, and she was driving slowly when she came around a bend and saw a man walking toward her, "a tall, lanky figure, and of course, it was Duke." He quickly got in the car and she asked what happened. Wayne explained that he'd started back from an evening with Dietrich, but his station wagon had hit a slick spot in the road and gone over an embankment. Wayne had jumped out before the crash, and had set out for Big Bear on foot. They got back to the location just as Hathaway was setting up his first shot. "I don't think he ever knew what was going on between Duke and Marlene," said Ollie Carey. But Hathaway knew. "They had quite a thing going," he remembered in 1980. "I don't think he realized that I knew the extent of their relationship, but I was aware of what was going on" (op. cit.: 111-112). A remake of a successful silent picture, 1941's "The Shepherd of the Hills" was adapted for the screen by Grover Jones and Stuart Anthony from a 1907 novel by Harold Bell Wright that reportedly sold 2 million copies. Betty Field (1916-1973) plays the love interest; in addition to Ward Bond, the credited cast includes Beulah Bondi, James Barton, Samuel S. Hinds, Marjorie Main, Marc Lawrence, John Qualen, Fuzzy Knight, Tom Fadden, Olin Howland, Dorothy Adams, Virita Campbell and Fern Emmett. Uncredited cast includes C.E. Anderson, Hank Bell, Henry Brandon, Nora Bush, Jim Corey, Douglas Deems, William Haade, John Harmon, Selmer Jackson, Carl Knowles, Bob Kortman, Ann Kunde, Charles Middleton, and Glen Walters.

LW3563: pdf of original magazine pages purchased 2019 by Leon Worden. Download individual pages here.

|

FULL MOVIE:

Broken Ways 1913

FULL MOVIE 1938

Fan Reply Card <1928

Marriages

Marked Men 1919

A Fight for Love 1919

Harry & Olive 1919

Overland Red 1920

Canyon of the Fools 1923

The Seventh Bandit 1926 (Mult.)

Satan Town 1926

Burning Bridges 1928

Trader Horn 1931

The Vanishing Legion 1931 (Mult.)

The Devil Horse 1932

Rustler's Paradise 1935

Last of the Clintons 1935

Port of Missing Girls 1938

With U.S. VP John Garner 1940

The Shepherd of the Hills 1941 (Mult.)

Hollywood Walk of Fame

Nat Levine 1988

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.