|

|

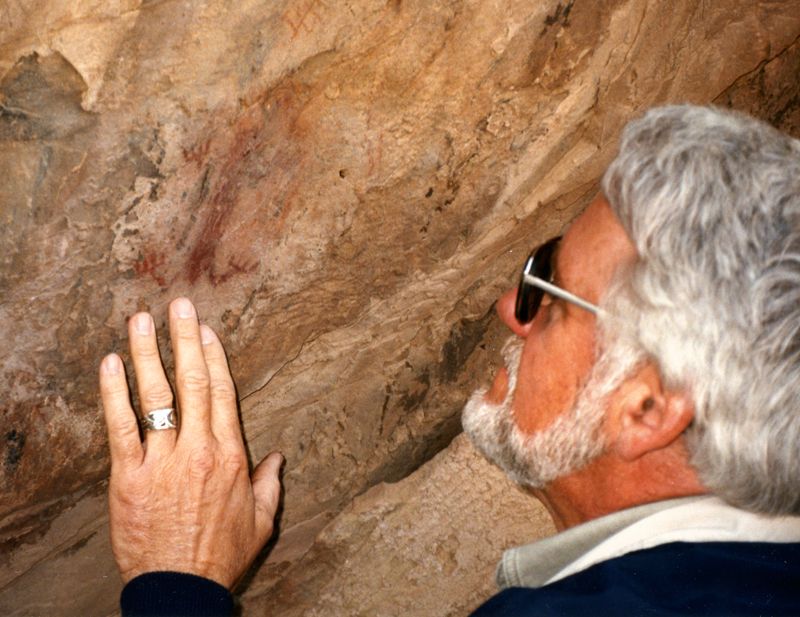

Vasquez Rocks County Park

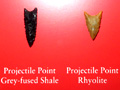

To get a sense of scale, Paul Higgins, an environmental educator and Santa Clarita city parks commissioner, examines a painting of a lizard at Vasquez Rocks. It's the same lizard seen in this photograph, shot at the same time. Photograph December 1995; the pictographs have been off-limits to the public since 1996. Most rock art was created by shamans, who were usually men, at the place where they entered the supernatural world. When the shaman exited his trance — induced by sensory deprivation, physical stress and a hallucigen, usually native tobacco and more rarely the dangerous jimsonweed — he would depict something he saw in a vision. In the case of pictographs, shamans painted in black (charcoal), red (either from hematite or a certain pond algae) and/or white (kaolin clay). Lizards are often found at entrances to caves and rock outcroppings used by shamans. Whitley (1996:20) writes: "Lizards and frogs ... crawl in and out of rocks through cracks or jump in and out of water, respectively, and this is analogous to a shaman's entry into the supernatural by metaphorically entering either a rock or a spring. These animals, therefore, were believed to be messengers between the mundane (i.e., "real" —Ed.) and supernatural worlds, and they were metaphors for the shaman's own ability to move back and forth between the mundane and the sacred realms. They might be portrayed on rocks to signal the locale as a portal to the supernatural." Rattlesnakes were guardians of the supernatural world; they were usually depicted as zig-zags or, as in this instance, a diamond chain. This rattlesnake painting could have been created by a shaman or it might have resulted from a girl's puberty rite; see the discussion here. We have no knowledge of the date of the art at Vasquez Rocks. Rock art in the Far West probably first appeared with the arrival of the first people and continued well after European contact. Realistically, any painting that's older than a century or two and is exposed to the elements, not in a cave, probably would have faded or worn away.

The Tataviam Indians, a Shoshone-speaking people, arrived in the Upper Santa Clara River Valley (Santa Clarita Valley) about AD 450. They occupied an area bounded by Piru to the west, Newhall to the south, the Liebre Mountains to the north, and Soledad Pass to the east. The word tataviam roughly translates into "People of the Sunny Slopes." Their Chumash neighbors on the coast called them "Aliklik," believed to be a derogatory term mimicking the clicking sound of their language. While it is not known exactly who preceded the Tataviam, the same area was occupied by a people, probably of Chumash origin, who arrived somewhere between 4,000 and 10,000 years ago. The Tataviam were hunter-gatherers who organized into a series of autonomous tribelets throughout the region. They ate acorns, yucca, juniper berries, sage seeds and islay, and they hunted small game. They likely practiced a shamanist religion that put them in touch with the supernatural world through trances and hallucinations brought on by the ingestion of jimsonweed, native tobacco and other psychoto-mimetic plants found along the local rivers and streams. Such habitats also provided raw materials for baskets, cordage and netting. The arrival of Spanish settlers in 1769 led to the demise of the Tataviam people. The Spanish rounded up the aborigines in the early 1800s and conscripted them for manual labor at the mission ranches and vineyards, where they intermarried with other native folk from other parts of Southern California. Juan José Fustero, who may have been the last local full-blooded indigenous person (his father was Tataviam, his mother Tataviam and Kitanemuk) died June 30, 1921, at Rancho Camulos, near Piru.* The Tataviam left behind a vast treasure of rock art at Vasquez Rocks, which is thought to have been a major trading crossroads. The Indians used berries, charcoal and other indigenous materials to emblazon a variety of images inside caves and onto the rock surfaces. Most images had religious meanings, and while they suffered both natural degredation and vandalism during the 20th Century, steps have been taken to preserve them. The most significant 40-acre region was closed to the public in 1996. * NOTE: While Fustero liked to bill himself as the "Last of the Piru Indians," an article in the Los Angeles Herald Examiner in 1965 says that Fustero may actually been married to a full-blooded Tataviam woman, and that they had children. According to the tribes that represent local Native American families, as of 1997 there were approximately 600 persons of Tataviam descent living in Los Angeles County. Further reading: The Tataviam: Early Newhall Residents by Paul Higgins.

LW9556: 19200 dpi jpeg from 4x6 print made from film shot by Leon Worden in December 1995. |

Bowers Cave Specimens (Mult.)

Bowers on Bowers Cave 1885

Stephen Bowers Bio

Bowers Cave: Perforated Stones (Henshaw 1887)

Bowers Cave: Van Valkenburgh 1952

• Bowers Cave Inventory (Elsasser & Heizer 1963)

Tony Newhall 1984

• Chiquita Landfill Expansion DEIR 2014: Bowers Cave Discussion

Vasquez Rock Art x8

Ethnobotany of Vasquez, Placerita (Brewer 2014)

Bowl x5

Basketry Fragment

Blum Ranch (Mult.)

Little Rock Creek

Grinding Stone, Chaguayanga

Fish Canyon Bedrock Mortars & Cupules x3

2 Steatite Bowls, Hydraulic Research 1968

Steatite Cup, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x5

Ceremonial Bar, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x4

Projectile Points (4), 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig

Paradise Ranch Earth Oven

Twined Water Bottle x14

Twined Basketry Fragment

Grinding Stones, Camulos

Arrow Straightener

Pestle

Basketry x2

Coiled Basket 1875

Riverpark, aka River Village (Mult.)

Riverpark Artifact Conveyance

Tesoro (San Francisquito) Bedrock Mortar

Mojave Desert: Burham Canyon Pictographs

Leona Valley Site (Disturbed 2001)

2 Baskets

So. Cal. Basket

Biface, Haskell Canyon

2 Mortars, 2 Pestles, Bouquet Canyon

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.