|

|

Eyewitness to the 20th Century

Ted "Bones" Sloan, LAPD.

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Sunday, December 16, 1984.

|

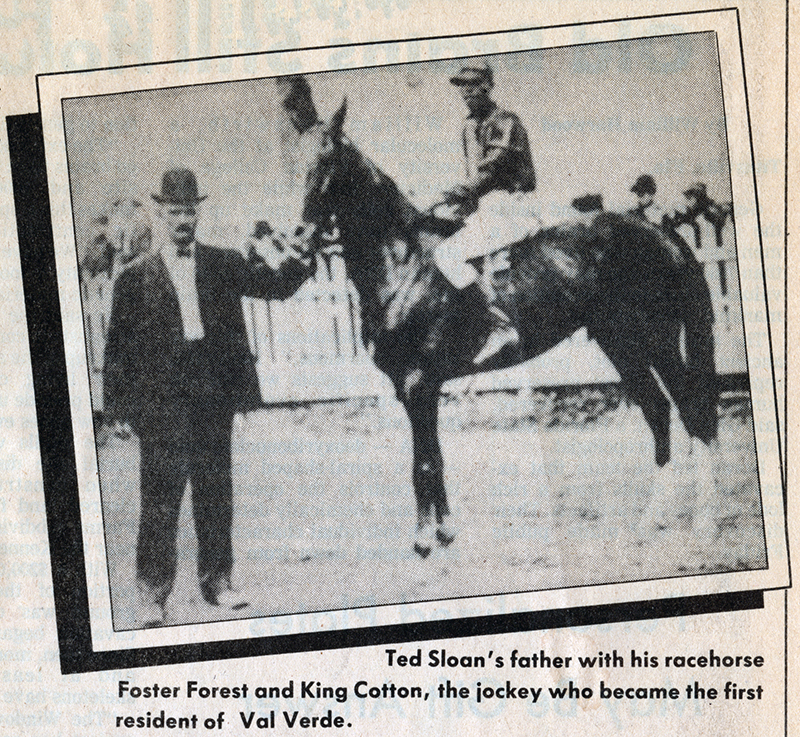

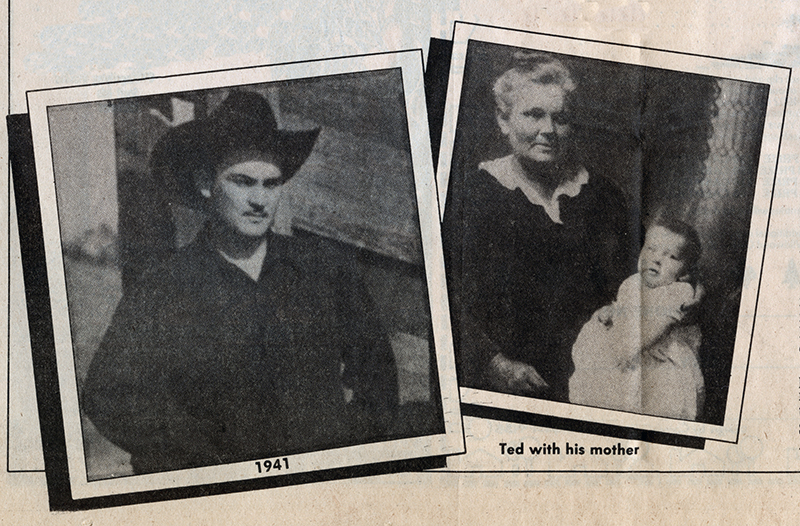

"I talked to a psychiatrist one time," said Bones Sloan. "I said, 'There must be something wrong with me. Is it an innate desire to die or something? "I'm always getting into gunfights.' "'Hell, no,' he said. 'You're about as stable a man as I've ever known. No, you're a hunter, and when you're out on that street, you're hunting those men just like you've hunted animals. "'Some men live on action,' he said. 'Common people, they don't even think about going into dangerous situations."' Sloan shrugged. "I've been like this all my life." Death never worried him, he said. "You get scared, but then you get brave, because you figure you're going anyway." Sloan is retired now, and lives on the Saugus ranch where he grew up hunting game for the family table. Still lean and muscular at 66, the only bad guys Bones Sloan goes after nowadays are the coyotes and bobcats which occasionally encroach on his property to eat the quail. He runs 10 or 12 head of cattle and grows grain to feed them. "Just something to keep me busy. I can't stand to sit here and watch that boob tube in the daytime." * * * Ted Sloan's father, a wealthy Los Angeles road contractor named Robert R. Sloan, did not want his children growing up in the city, so he bought 160 acres in Hasley Canyon at $2.50 an acre and sent his children, wife and racehorses there to live in 1903. Ted Sloan was born in 1918, the youngest of 11 children, and grew up a country boy, as his father had wished. In those days, that meant generous, clean-cut and tough. "If we were sitting down to dinner and you would walk in the house, even if we'd never seen you before, you would be invited to sit down at the table," Sloan said. "You don't see that in town. But real Californians that were born and raised here, that's the way they all were. "We were different from city kids. "To have fun, we'd go to French Village (a Newhall dance hall) to dance. If we wore our only good pair of pants and took a girl, then other local guys wouldn't pick on us. You know, you didn't want to turn on a guy who had a good pair of pants on. "But sometimes we'd wear Levis and then we'd pick fights with the city guys. They'd come up and they'd be drinking and everything. They'd insult us, call us country boys. "And in a way, I guess we were a little bit ignorant. But we were brought up to treat a girl with respect. We didn't drink, we didn't smoke, we didn't do any of those things. We all hunted deer and rode broncs and all that. "You notice the difference in people raised up here. Not just here, but Idaho, Montana. They aren't like city people. They aren't selfish — they always help everybody else. "We were raised that way. We weren't religious at all. We had to go to Sunday school, and I think that's probably why I never went to church anymore. I had to read the Bible every night. I liked it the first few times I read it — it was all about fighting." The Sloans and their neighbors were closed-mouthed about one another's business, keeping to themselves an old Spanish gold mine they discovered, a perpetual motion machine invented by Mr. Lechler, and — during Prohibition — the stills operating at a neighboring ranch up the road from the Sloans. "We liked the people that lived there," Sloan said. "They were just props, living there like it was a ranch, but you didn't see them raising any cattle or anything like that, just a few hogs and chickens.

"We didn't tell anybody about it. Country people used to be that way. Clannish, you know? You never stooled on a neighbor about anything. "We thought it was funny. The teacher didn't, though. She found out about it somehow. I think she heard about the ducks and chickens all wandering around drunk. They'd throw out the grain they made the booze out of, and the chickens and the hogs would all get drunk eating it. "They raided that thing, and I think there was three truck trailer loads of that imported cognac and stuff that went out of there. Somebody said only one truck made it to the sheriffs in L.A. "We had nothing to do with it. My old man, he never touched it in his life. Never smoked, either." Robert Sloan retired from the contracting business in the '20s and left Los Angeles to live on his ranch, which he had expanded to about 3,500 acres. When the crash of 1929 came, he lost his fortune. The greater part of the ranch and his land holdings in Los Angeles were lost when he could not come up with $500 for the tax collector. In spite of his father's financial reversal, Ted Sloan says he had a wonderful childhood. He remembers his father as "a big, quiet man who didn't have much to say." Robert Sloan was six-foot-four, a blue-eyed, black-haired Irishman whom people called "Old Catcher's Mitt" when his back was turned because of the size of his hands. Ted Sloan remembers sitting in his father's lap as the big man roared old Irish tunes and stamped his size-15 feet on the floor to keep time, while Ted's mother picked up her skirts and danced the schottische. She was a big woman, but Ted Sloan recalls she danced "light as a feather." "We had a happy family," he said. Both of Ted Sloan's parents were descended from Irish families who came to America before the Revolution. One of their grandfathers was a general in the War of Independence. They remained jealous of one another all their lives; even after their 50th anniversary, Robert Sloan would become upset if he thought his wife was going to the town shoemaker too often. The neighbors had to scramble to keep up with the Sloans. "My old man, he was always ahead of everybody," says Ted Sloan. The Sloan family had a gas generator which provided the first electric lights in the area, long before commercial electricity came to the area in 1950. They also had hot water from a storage tank Robert Sloan made by encasing a barrel in adobe and concrete. The water was heated by a wood fire and stayed hot for two or three days. Hasley Canyon and Sloan Canyon roads, which Robert Sloan put in with mule teams, still exist. So does the two-story prefabricated house he hauled into Sloan Canyon on wagons drawn by mule teams. And so does the little one-room schoolhouse where began the studies of Bones Sloan, who later graduated second in a USC class which included men like Tom Bradley — now mayor of Los Angeles — and Ed Davis, former Los Angeles chief of police and now state senator. As the youngest boy in the family, Ted Sloan was responsible for putting meat on the table. He was 8 when he shot his first buck with a .22. He was too small to lift it by himself, so his brother Bud came and helped him bring it home. "We cut our teeth on the gun barrel," said Sloan. "First thing we were taught was to shoot." But hunting was never for pleasure: "My old man taught us, you don't shoot something unless it's something you're going to eat. We never wasted anything." His chores also included milking 20 cows and caring for 50 stands of bees. The bees would swarm all over him without stinging. His father was also a good hand with bees. At Robert Sloan's funeral, a swarm of bees followed the hearse to the cemetery and hovered overhead while the casket was lowered into the grave. People drought it unusual since there were no flowers in the hearse. During school vacations, Ted and Bud Sloan would "pearl dive" (wash dishes) 12 hours a day at the Beacon Coffee Shop at the junction of Highway 99 and Highway 126, for Robert Sloan believed his children should learn to work for what they got. Robert Sloan's wife, Bertha May Opp, ran the first foster home in Los Angeles County. The "County boys" slept in a 90-foot dormitory built by Robert Sloan and ate on a 30-foot long table. They were treated like the Sloan's own children, and Ted Sloan slept Army-style in the dormitory and ate at the long table. Robert Sloan was not a belligerent man — he never started a fight — but he expected all the children to know who was boss. "If I played around at the dinner table," said Ted Sloan, "he'd say 'Boy...' and that's all he had to do. I ate the bottom out of that plate." Once an especially rough boy was placed on the Sloan ranch as a last chance before being sent to a tough juvenile prison. He was a big redhead, about six-foot-two, and seemed to be on the way to San Quentin. "He looked at Pop, and he says, 'Old man, might as well get something straight: I'm going to be king of the mountain.' And Pop says, 'What do you mean by that?' And he says, 'Well, you're not going to be the boss as long as I'm here.' "Pop says, 'Son, I want to treat you right. But if you think you can take me, just shoot your best shot.' "And the redhead swung at him, and my dad slapped him open-handed on the side of the head. He did a complete backward somersault. My dad was six-four and about 250, and there was no fat on him. My God, he was a big man." The experience seemed to have a beneficial effect on the redheaded boy. "Instead of hating Pop, he just got to where my dad was his idol. I guess his own father didn't care whether he lived or died, and he'd never had a chance." Bertha May Opp's County boys came back to see her until she died, bringing along their families and their success stories. The tough redheaded boy became deputy chief of police in Long Beach. * * *

He began his career in the Los Angeles Police Department in 1940, at the age of 21. "I was a street cop," he says. "From one cop to another, that is like saying you got the Medal of Honor. A street cop has no use for the politicals, the ones that go to the parties and get drunk and all that. When I got through work, I came home. If I had to brownnose a bunch of damn politicians, why, I'd stay where I was." He nevertheless rose to deputy commander and was responsible for the robbery division. The first day Ted Sloan went out on the street in uniform, he felt "like neon." After a few days, he was assigned to work undercover for the vice squad because he looked so young. "I'd go in and tell some lie and the madam would introduce me to all the girls, and I'd take out a whole house. I hated it. I felt like a sneak thief. "Then they put me driving a yellow cab undercover. You'd take the tricks and you'd take the guys to go gambling. But I would not turn in the other drivers; I just couldn't do that. I'd turn in the pimps and the houses that would run the games. But turning in the guys you're working with — those guys would tell you things because they thought you were just a plain driver. "I couldn't get out of it. I'd get out of one vice, and another vice squad would reach out and snatch me, and there wasn't a thing I could do about it. So I went to the deputy chief, and I said, 'I don't think I want to stay on the job any longer. I didn't come on here to be a stool pigeon, I came on to be a cop."' The deputy chief said, "When you come on, you do what you're told." After two years, the department relented and put Sloan back in uniform. Shortly thereafter he enlisted in the Army after a minesweeper carrying one of his brothers was sunk in Salerno Bay, Italy. His brother and four others survived, but they went mad from the underwater implosion when the mines aboard the ship exploded and were sent back to the United States in strait jackets. With shock therapy — a new, untested treatment — they all recovered their sanity. Ted Sloan was still in Army Air Force pilot training when the combat gunners began coming home, and he was sent back to the police department instead of overseas. After the war, he studied public administration at USC on the GI Bill. While attending USC, he worked full time for the police department and moonlighted as a bouncer on weekends. In spite of so many extracurricular activities, he was graduated with a 3.85 average. He and his classmates became the ruling elite of the Los Angeles Police Department, which had reached a low point in 1936 when the police chief and mayor were ousted for corruption. Under the leadership of the renowned police chief William H. Parker — an uncompromising man described as a Calvinist by Joseph Wambaugh in "The New Centurions," one of several books immortalizing the Los Angeles Police Department — the force became the best in the United States in FBI ratings. It was and is, says Ted Sloan, "the only honest major police department in the United States." The present police chief, Darryl Gates, was "Parker's handpicked man," Sloan said. Parker was Sloan's idol. "If you made an honest mistake, he would back you all the way." But if the mistake was not honest, "you had better give your soul to Jesus." Sloan's photographic memory was an asset in detective work. "I'd be off a couple days, and the first thing I'd do would be to sit down and read every report of a robbery committed anywhere in the city of L.A. Every bank robbery stopped at my desk. "When I retired, my squad had 92 percent clearance rating on bank robberies. And one-quarter of all the bank robberies in the United States occur in the city of Los Angeles." When Sloan made lieutenant, there were only 140 men of that rank in a police force of 7,000. Today the size of the force is the same but there are 1,100 lieutenants. "They're all brass, all chiefs and no Indians," said Sloan. * * * He left the police department in 1967 to spend four years as a police adviser in Vietnam. He liked and respected the Vietnamese and got along well enough with them to turn down their gourmet delicacies — chicken heads, for example — without anyone losing face. "If ever I saw a people who were natural capitalists, it was the Vietnamese. You watch them go into business: They will make out, because they work hard and they save. You had to respect them." He managed to be out on the days the Vietcong shelled his house, but was wounded three times. For a time, he was stationed in Bac Lieu, a South Vietnamese town which, he says, like most of the towns in Asia, was called the Pearl of the Orient. Raw sewage flowed in the streets of the Pearl, as it did in the other towns in the provinces. Dysentery was common. The Americans drank bottled water, but during the 1968 Tet offensive, the compound Sloan was in was besieged, and water supplies ran out. He contracted an amoeba which was supposed to disintegrate the liver in six months, and went from 180 pounds to 80 pounds, but recovered. * * * Today, Ted Sloan lives with his son Ted and his dog Eric on the ranch where he was born. His daughter is in the Highway Patrol, as is her husband. He has three grandchildren. He used to be able to "see a gnat on a fly's fanny up on the hill" but wears reading glasses now. A portrait of his hero, John Wayne, hangs in a prominent place among the hunting trophies in his wood-paneled living room. Hunters sometimes trespass in Sloan Canyon to shoot local deer, and Sloan took down the top row of barbed wire on his fence so the deer could jump over it to escape. For the fawns, he made a door through the fence. He never drank and does not now. He started to smoke during one of his stays in the hospital but does not inhale. He talks of the changes in the area with sadness. "My God, you never saw slaughter like is going on now. Every time I pick this little paper up I can't believe it. Rapes and murders — we never had that here at all." The increased violence, he said, started when courts prohibited the enforcement of the death penalty. His experiences have left him with definite ideas on civil rights: "I think everybody should be treated the same. I don't care if they're black, white, red, yellow or what. I don't knuckle under anybody, and the day will never come when I will. I think the police department should represent all the people, protect all the people the same amount. If they're wrong, they go to jail. If they're not, why, let 'em go. "I never had much problem with people, because I treated them the way I wanted to be treated. And you know, that works pretty well in life. It seemed to with me." This is the ninth biographical profile of The Signal's series of "Eyewitness To The 20th Century." The series concludes Wednesday.

Download individual pages here. Clipping courtesy of Cynthia Neal-Harris, 2019.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.