Mentryville: Origins of Standard Oil Co. of California.

|

Webmaster's Note. "Among Ourselves" was a magazine published monthly in San Francisco for employees of the Standard Oil Company of California. This copy belonged to Charles E. Sitzman, then-superintendent of the Pico Canyon (Mentryville) oil field.

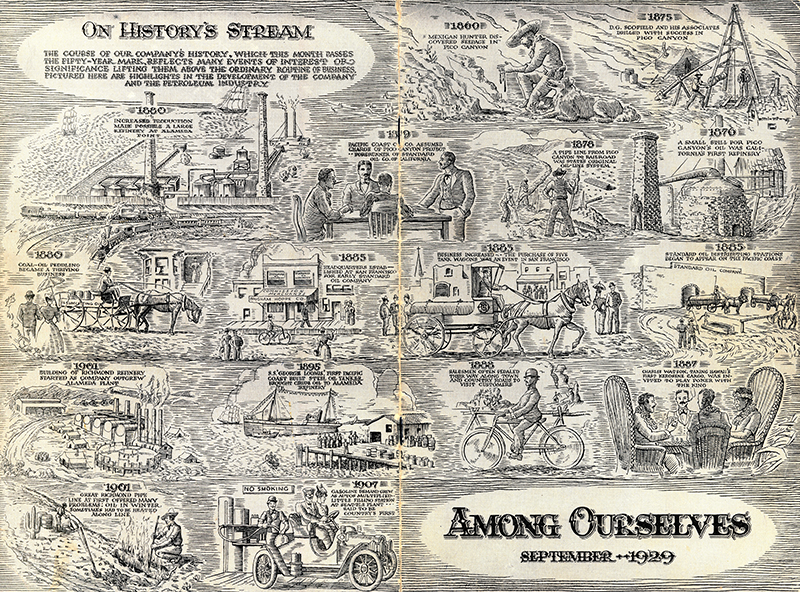

[Dedication.] A half-century now marks the lifetime of our organization — the time which has elapsed since the memorable day when a group of early California oilmen, comprising the newly formed Pacific Coast Oil Company, took over the work of the California Star Oil Works Company at Pico Canyon. Then began the period of growth and expansion which still continues and which led to the present Standard Oil Company of California. To this group of men and to all other Company pioneers of the intervening years this issue of Among Ourselves is dedicated. It Was Many Years Ago... A young man, searching for some documents through the dusty recesses of a certain vault in this Company's Home Office building the other day, came across a slim packet of quaint-looking papers. "What are these?" he exclaimed. "I never heard of this outfit before — the California Star Oil Works Company. Why, these are stock certificates! They look more like receipts, don't they?" — humorously displaying one of the plain-appearing slips of paper. "Let's see, when was this company incorporated — 1876! Well, that was before our time." And he tossed the bundle back into the vault and continued his quest. "Just a moment," we pleaded, taking the faded papers to the window. These were the stock certificates of the little organization of stout-hearted pioneers whose courage, faith, and capital meant so much to California more than a half-century ago. They were relics of a time when there was no oil industry in the state, when commercial production was a mere dream inspired by the glamorous tales of discoveries of petroleum in Pennsylvania and other Eastern states. There were scoffers in that day as there have been from the beginning of time. "Oil? hah!" they would answer. "A few pools of sticky, smelly stuff just good for Indians to rub on rheumatic joints, or to take the squeaks from wagons!" But to think of the Far West producing oil in quantity of any commercial value — that was preposterous! Let us now stop a few moments to learn something about the story represented by these faded documents lying forgotten in our vaults. Let us hear of that small company and what it had to do with our present organization. * * * When we came to this Company some years ago, a slight, gray-haired gentleman, of unobtrusive manner and with kindly eyes, used to greet us every time we met in the corridors or elevators of the Home Office building. Young, strange to the business world, we conjectured often as to this man who treated everyone so courteously. "That is Mr. Scofield, our president," we were told. "He's the same to everyone, from the members of his board to the youngest office boy." Perhaps many readers may not be familiar with the name of D.G. Scofield, let alone having met the man, for in the long period of years this Company has existed, many men have come and gone. But this pleasant official came to California as a youth, nearly sixty years ago, when "oil" was the word on everyone's lips. The great fabulous tales of the East were bandied from mouth to mouth. There were strange stories, too, of oil seepages seen in the mountains on the Pacific Coast not far from San Buenaventura. Adventurous souls had tunneled into the mountainsides and petroleum was said to have run out in streams. Attempts had been made to sink wells. But, when oil was encountered, it proved to be a heavy fluid commanding no market. Shrewdly, Scofield traveled over this region in southern California from whence the many rumors were emanating. He had come from Pennsylvania and was familiar with the geological evidences of the location of oil. He heard the story of a Mexican sheepherder, who, while trailing a deer, had discovered a seepage of black fluid at the head of the almost inaccessible Pico Canyon in the rugged Santa Susana Mountains. The Mexican had taken a sample of the fluid in his canteen to the little mission settlement of San Fernando not many miles away. It was looked upon as an oddity until one wise person identified it as crude petroleum. Tradition has it that the sheepherder took out a claim but later readily relinquished it for a barrel of whisky! It was fifteen years later that Scofield found that the claim had changed hands a number of times, but that no development had been effected. Investigation made him confident that oil was in those mountains. He came to San Francisco, where he interested others in the oil-producing possibilities of Pico Canyon, the mayor of the city being one of those who joined Scofield's organization. Thus came into existence, on June 16, 1876, the California Star Oil Works Company, a truly formidable name for such a small firm, but reflecting its boldness. Remember, fifty-three years ago California was a young state with few cities, and those still linked mainly by El Camino Real. The coming of railroads was but optimistic talk. The lofty ranges between Pico Canyon and the south offered great barriers which had to be conquered by the teams that hauled heavy equipment from San Pedro, where most of it had been delivered by sailing-vessels after rounding the Horn and. visiting San Francisco. General Manager Scofield, filled with optimism, sought and found in the big, bearded Alex Mentry, carpenter of Los Angeles, a foreman who immediately displayed as much enthusiasm over the project as his superior. They went into the fastnesses of the Santa Susana Mountains, into the Minnie-Lottie Canyon, through which tumbled Pico Creek, and there built a tiny community — "Mentryville," they called it. It's there today, still shut off from the rest of the world and almost forgotten. At the very head of the steep Pico Canyon, where seeped the black stuff that had intrigued the sheepherder, they sunk their first well not with a tall steel derrick, nor powerful steam apparatus, nor rotary equipment such as you and I know of today, but by a primitive spring-pole device, consisting of a sapling secured beneath a tripod derrick. A bit, hung on a cable from the sapling, made depth by being sent forcibly to the bottom of the hole by the weight of two men applied to the cable, the spring-pole raising the bit for each succeeding stroke. A hand-operated windlass furnished more cable as the hole deepened. A month's time showed thirty feet of hole, with the happy result of a daily production of two barrels of oil of 32 degrees gravity. Across the canyon a second well went down by the same crude means, and again oil came in — good, high-gravity oil. A third well proved to be a dry hole. Elated with the results of the first two wells, Scofield increased his forces; another well was drilled. That was No. 4, the pride of all time. This same No. 4 well exists today, and has faithfully produced from the beginning. Scofield, in the meantime, brought Jim Scott out from Titusville, Pennsylvania, to build a refinery. One still was hurriedly set up at Lyons Station on the stage road that crossed the Tehachapi Mountains and led into Los Angeles. Another refining unit was erected at San Buenaventura on the coast. The three years following, these "refineries" had a daily capacity of sixty barrels. It was in 1878 that the single still at Lyons Station was moved a mile or so north to Elayon. Here two additional stills were built and the output increased to one hundred barrels daily. Crude oil was freighted over the mountains from the wells to the refineries, in second-hand wooden barrels. After three years of heart-breaking exploitation and attempts to refine oil in those lonely mountains, even the cheerful-minded Scofield shook his head dismally, for the expense of producing and manufacturing was exceeding the returns. But this able leader was not daunted. He went to his associates in San Francisco and informed them that either the Pico Canyon enterprise must cease, its derricks rot, and its equipment turn red with rust, as had been the outcome of certain predecessors, or more money must be had. Scofield believed implicitly in California as an oil producer, and his extreme confidence prevailed. With additional capital, such men as Senator C.N. Felton, Lloyd Tevis and George Loomis joined forces with Scofield. * * * A new concern was incorporated, known as the Pacific Coast Oil Company. This was on September 10, 1879. Felton was the president, and Scofield general manager. It is that date with which begins the corporate existence of the Standard Oil Company in California. The little field bustled anew — hope rose again in the tiny settlement of Mentryville: housewives once more sang happily, and children romped gaily in play, for they need not leave their mountain homes. New wells were sunk in the adjacent Wiley Canyon with a reward of early production. Bunkhouses sprang up here, as did long stables for many mules and horses. Production soon climbed to six hundred barrels a day. A two-inch pipeline was laid in the latter part of 1880 — the first oil line in California. It led from the wells in Pico Canyon to Elayon, where railroad loading-racks were constructed, for the Southern Pacific Company had in the meanwhile linked the south with San Francisco. With high hopes, plans were developed for a large refinery on San Francisco Bay, and this was quickly erected on the westerly point of Alameda. With the completion of this refinery, the plants at Elayon and Ventura were abandoned. The former plant, a mass of crumbled ruins, is to be found today in the rank vegetation on the outskirts of the present town of Newhall. Tank-cars were loaded at Elayon and brought the oil to San Francisco. And such tank-cars perhaps you never saw — they were merely freight-cars with an upright tank at each end and a center space providing for freight to be carried on the return trip. In those days carrying oil was not particularly lucrative. Fifteen years later the enterprising Pacific Coast Oil Company built a tanker, the "George Loomis," named after the company's second president. It was the first steel oil-tanker constructed and operated on the Pacific Coast, and the second steel steam-driven tanker built in the United States. This craft, 175 feet in length, had a cargo capacity of about 6,500 barrels — quite a contrast to the 512-foot motorship "California Standard" with its cargo capacity of 137,138 barrels! During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Scofield and his associates struggled with the discouraging problem of producing California crude and converting it into kerosene and other useful products. Failure met every effort! From 1876 to 1900, as Scofield once recounted, "we had made every effort possible, regardless of expense, to manufacture a perfect refined oil — kerosene — and one that could be universally sold upon its own merits, but all such attempts had resulted in failure and entailed heavy losses." * * * Now let us turn back some years in our narration. A few years after Colonel Drake brought in his historic well in Pennsylvania, in 1859, among those becoming interested in the budding oil industry was a young man — John D. Rockefeller. It was in 1870 that he and his associates, following several years of experience, formed the Standard Oil Company in Cleveland, Ohio. Successful management brought phenomenal expansion to this enterprise, so that in the early years of our own Scofield's exploitation in California, the products of the Standard Oil Company, mainly kerosene, axle grease, candles, and lubricants, were marketed nationwide and later world-wide. Sailing vessels brought cargoes of kerosene in tins and cases around the Horn to the Pacific Coast. Jobbers received consignments, directly at first, and in turn supplied the retail trade. One of the prominent distributors in San Francisco was Yates & Company. This firm amazed the metropolis by the Golden Gate in 1883 by having five tank-wagons built to distribute Standard Oil kerosene. The late "Mike" O'Connor proudly led the quintet of shining red-and-blue vehicles through the lazy traffic of early Market Street! In 1885 the Standard Oil Company established Pacific Coast headquarters in this city. A small suite, with three employees, was opened in California Street over the shop of Brigham, Hoppe Company, commission merchants. Then began the establishment of distributing stations throughout the Pacific Coast, which were the forerunners of the sales agencies this Company has today. Many of the employees who came to that early company were destined later to play important roles in the great organization that the Standard Oil Company came to be on the Pacific Coast. There was Charlie Watson, now with his forebears, who traveled from one end of the coast to the other, engaged in furthering every phase of the business. In 1887 that doughty executive accompanied a cargo of ten thousand cases of kerosene to Honolulu to establish distribution at the Crossroads of the Pacific. There was then a king ruling over the islands, and the redoubtable Watson played several games of the good old Nevada Poker with his majesty! The sky was the limit, and the very first night the king got "skinned" — but later he had Watson going badly. Then there was J.C. Fitzsimmons, who at the time of the gold rush to Alaska in the nineties sailed from Seattle in a high-superstructured river boat — the only craft available. It was heavily loaded with kerosene, candles, and other petroleum products which were subsequently exchanged for the miners' gold-dust. "J.C." took his little vessel up the Inside Passage into the north Pacific and the Bering Sea, where a valiant battle was fought with wind and waves. The crew never was entirely certain of its fate until St. Michael was reached. Many stirring tales could be recounted of those early days of the Standard Oil Company, and a lengthy roster could be made of those men whose courage and faith largely made possible the successful organization we know today. * * * With the dawn of the new century, the Pacific Coast Oil Company joined the Standard Oil Company, bringing together two notable groups of pioneers to whom must go much of the credit for building the great oil industry of the Pacific West. The twentieth century saw the remarkable transition of this industry, when the banner product — kerosene — gave way to the once almost useless gasoline. Our story should rightly proceed, for many have been the projects launched in every phase of our business: great oil-fields have been developed by Standard Oil men, vast refineries erected, vitally important pipeline systems constructed, a splendid sales-field evolved, and a mighty fleet of tankers created. But let us stop now, in homage to those small groups of men who strove for a quarter of a century in just laying a foundation upon which now rests this edifice of ours — this organization, the Standard Oil Company of California.

SZ2901: pdf of original magazine, Charles E. Sitzman Collection, Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. Download individual pages here.

|