|

|

Abel Stearns Tells of Lopez 1842 Gold Discovery; No Mention of Dream.

Correspondence of July 8, 1867 | Published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel, August 27, 1885.

|

Webmaster's note.

Much of what we know about Francisco Lopez's discovery of gold in Placerita Canyon in March 1842, if that was indeed the month, year and location (some argue for 1841, some for San Francisquito or San Feliciano Canyon), comes from a letter written from memory 25 years later by Abel Stearns, L.A.'s leading merchant of the 1830s and 1840s, who in 1842 sent California gold dust to the U.S. Mint at Philadelphia for assay. Stearns' 1867 letter, which has been published countless times in countless places ever since it was written, describes what Lopez told him of the discovery: that Lopez and company reportedly stopped under some trees and tied up their horses, and then, "with his sheath knife, [Lopez] dug up some wild onions, and in the dirt discovered a piece of gold, and searching further found some more." It's a phrase familiar to every ardent student of Santa Clarita Valley history by virtue of its repetition. Two things are absent from Stearns' recapitulation, as published in full below: a dream myth, and a reference to any particular oak tree. Those came later. The dream myth first appears in the 1930 version of the story as told from memory, second-hand, by Francisca Lopez de Belderrain, an indirect third-generation descendant of the discoverer. Likewise, we haven't seen an earlier reference to the Oak of the Golden Dream than Adolfo G. Rivera's correspondence and speech at the 1930 dedication, which was orchestrated to give L.A. County its due. It wasn't the first time Southern California historians, including our own A.B. Perkins, were getting short shrift from their northern neighbors – as evidenced in this 1885 news article — nor would it be the last. One unsettling aspect of Stearns' letter is his placement of the discovery at "San Francisquito." We don't know what that means. On the one hand, it could mean San Francisquito Canyon, where gold occurs in placer form even today. On the other hand, we don't know what Placerita Canyon was called before it was called Placerita Canyon. The name obviously didn't predate the 1840s, inasmuch as no "placere" was known there. By 1839, and probably by the early 1820s, most of the Santa Clarita Valley was the Rancho San Francisco, and we have encountered "San Francisquito" in colloquial usage, possibly to avoid confusion with the "other" San Francisco. Maybe Stearns was using the colloquial term for the broader region. Or maybe, if we apply Occam's razor, the discovery was made in San Francisquito Canyon. Or maybe the razor was dull and Stearns' (1798-1871) memory was fading. All we really know is that the history of California didn't start with the American takeover, and James Marshall wasn't the first to find gold here.

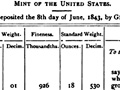

Bogus History. Angelenos the First Argonauts. Santa Cruz Sentinel | August 27, 1885. The Sacramento journals are being greatly exercised in regard to a piece of bogus history about the discovery of gold in California by James W. Marshall, on the 18th of January, 1848. The [Sacramento] Bee gives his history as follows: "James Wilson Marshall was the first discoverer of gold in California, and his name is inseparably connected with the history of this State. He was born in Hope township, Hunterdon county, New Jersey, in 1812. He learned the trade of a coach and wagon builder, but his early life presents no features of particular interest. When he arrived at the age of 21 years he caught what is still known in the East as the "Western fever," and he journeyed first to Indiana, then to Illinois, and finally to the Platte Purchase, near Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Here he purchased a farm, and was prospering, when he was attacked with malaria, and after struggling with the disease for some years, he was told by his physician that he must leave the location if he wished to live. On the 1st day of May, 1844, Marshall, with a train of 100 wagons, set out for California, which was not reached until June, 1845. Marshall went to work for General Sutter, at Sutter's Fort, in this county. He afterwards served throughout the Bear Flag war, 1846 and 1847, and at its close procured his discharge, and went into the lumbering business at Coloma, El Dorado county. General Sutter furnished the capital, and Marshall was the active partner. The articles of partnership were drawn up by General Bidwell, and work was commenced on the mill about August 19, 1847. On the 18th day of January, 1848, Marshall was superintending the building of the mill race. After shutting off the water at the head of the race, he walked down the ditch to see what sand and gravel had been removed during the previous night. At the lower end of the race, among the debris, his eye caught sight of a glittering substance, which he believed, upon examination, to be gold. In several days he collected a few ounces of the precious metal, and as he had occasion to visit Sutter's Fort, in a short time, he took the specimens with him, and their value was established beyond doubt. The news spread, and the furious race for wealth commenced. In 1849 every sailing vessel and steamer landing at San Francisco was crowded with adventurers. They knew that gold had first been found at Coloma, and many went thither. Without inquiry or negotiation they squatted upon Marshall's land about the mill, seized his work oxen for food, confiscated his horses, and marked the land off into town lots and distributed them among themselves. From this time on Marshall was the victim of petty persecutions. Many believed that he knew of the whereabouts of valuable gold mines, and he was watched closely and badgered became he did not give information. Robbed of his property, he became a prospector, but never with great success. The discovery which brought fortunes to thousands, and made California a great State, proved his financial ruin, and subjected him to endless insults and injuries. He became involved in litigation as to the title of his land, purchased in 1846 or 1847, and finally lost it all. He resided at Coloma near the spot where, 37 years ago, he picked the glittering nugget from the sand. He has received some assistance from the State, but never anything commensurate with his deserts, and he died a poor man." The True History. Thus endeth the bogus history. The facts have been published several times in Los Angeles, and notably in the Illustrated Herald of January, 1885. Gold in California was first discovered in Los Angeles county in 1842, in the month of March, by Francisco Lopez. Mr. Alfred Robinson, at present a prominent citizen of San Francisco, took the gold first discovered to the mint at Philadelphia, where it was minted July 8, 1843, for account of Don Abel Stearns, of this city. The newspapers that publish this bogus history might be benefited by publishing the facts as accurately stated in the Herald. Following is the history of the Discovery of Gold In California, to which the attention of the Sacramento journals is called. Los Angeles, July 8th, 1867. Louis R. Lull, Esq., Secretary of the Society of Pioneers, San Francisco: — Sir: On my arrival here from San Francisco, some days since, I received your letter of June 3d last past, requesting the certificate of assay on gold sent by me to the mint of Philadelphia in 1842. I find by referring to my old account books that November 22d, 1842, I sent by Alfred Robinson, Esq., (who returned from California to the States by the way of Mexico), twenty ounces California weight (18¾ ounces mint weight) of placer gold, to be forwarded by him to the United States mint at Philadelphia for assay. In his letter to me, dated August 6th, 1843, you will find a copy from the mint assay of the gold, which letter I herewith enclose to you to be placed in the archives of the Society. The placer mines from which this gold was taken was first discovered by Francisco Lopez, a native of California, in the month of March, 1842, at a place called San Francisquito, about thirty-five miles north-west of this city [Los Angeles]. The circumstances of the discovery by Lopez, as related by him, are as follows: Lopez with a companion, was out in search of some stray horses, and about midday they stopped under some trees and tied their horses out to feed, they resting under the shade; when Lopez with his sheath knife dug up some wild onions, and in the dirt discovered a piece of gold, and searching further found some more. He brought these to town and showed them to his friends, who at once declared there must be a placer of gold. This news being circulated; numbers of citizens went to the place and commenced prospecting in the neighborhood, and found it to be a fact that there was a placer of gold. After being satisfied many persons returned; some remained, particularly Sonorensee (Sonorians), who were accustomed to work in placers. They met with good success. From this time the placers were worked with more or less success, and principally by Sonorensee (Sonorians), until the latter part of 1846, when most of the Sonorensee left with Captain Flores for Sonora. While worked there was some six or eight thousand dollars taken out per annum. Abel Stearns. Letter from Mr. Robinson. New York, August 6, 1843. My Dear D. Abel: I embrace this opportunity of the sailing of a ship from Boston to address you a few lines, and therein to inform you of the result of your shipment of gold, which is as follows, as per statement from the mint at Philadelphia: "Memorandum of gold bullion deposited the 8th day of July, 1843, at the mint of the United States at Philadelphia, by Grant & Stone, of weight and value as follows: "Before melting, 18 34-100 oz.; after melting, 19 1-100 oz.; fineness, 926-1000; value, $344.75; deduct expenses, sending to Philadelphia and agency there, $4.02; net $340.73. A Robinson. News story courtesy of Lauren Parker.

|

Dissecting the Dream: Fact, Fiction & the Golden Oak, by Alan Pollack

New York Observer 10-1-1842

U.S. Treasury Voucher 1843

Abel Stearns Letter 1867

Francisco Lopez

Pedro Lopez (Brother)

Maria Felis (Wife)

Maria Concepcion (Daughter)

Francisco Ramon (Son)

Catalina (Pedro's Daughter)

Francisco "Chico" Lopez Obituary 1900

As Told by Jose Jesus Lopez

Sutter's Fort Error 1905

Prudhomme 1922

Engelhardt 1927

Francisca Lopez de Belderrain

Belderrain Story 1930

Who's Who, by Belderrain

• Story: Sutter, Marshall Knew They Weren't First

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.