|

|

Bowers Cave | Peabody Museum

Tataviam large coiled storage basket with small mouth, found in Bowers Cave in the San Martin Mountains (present-day Val Verde area) in 1884. In the collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Peabody Catalog No. 39243. 21 inches in diameter, 10 inches tall. Bound-under juncus wefts, partially worn away to expoose a deergrass bundle foundation. Traces of asphaltum on exterior, probably for waterproofing. Residue of acorn meal inside. Archaeological. Note: What might appear to be a lid is actually just the shape of the basket. It's broken at the shoulder. The opening at top is much smaller than the shoulder and is not easily visible from this angle. Peabody's description reads: Large basket from a cave in the San Martin Mountains, outside of Los Angeles, So. California. Gift of Dr. Stephen Bowers, 1885. Elsasser and Heizer (1963) describe this basket together with Nos. 39242 and 39244 as follows: These three specimens ... are complete; they are not made up of fragments which have been added to, presumably after being damaged. All have asphaltum on their outer surfaces, especially on the lower portions ... (39243 is) clean inside except for (its) bottom, which (is) partially covered with an agglomerate substance perhaps identifiable as acorn mush mixed with fine sand or silt. The start[] of (this basket is) slightly reinforced by the sewing of a few stitches of grass at (its bottom center). (The rim of this basket is) of the type called self rims[;] the last coil of the basket is therefore much like the preceding coil in structure, except that the grass foundation bundle is thinned down near its end. The moving end of the last splint was secured simply by running it back under 5 or 6 stitches and then passing it through the foundation itself. This basket is depicted in color in Shanks and Shanks (2010). Their photo caption reads: This Tataviam coiled storage basket has a broad shoulder and small mouth. It is done with juncus wefts on a deergrass bundle coil foundation with bound-under weft fag ends. It is a noteworthy Tataviam form.

Shanks and Shanks (2010) reexamine the Bowers Cave[1] basketry (pp. 52-57). They disagree with Elsasser and Heizer's (1963) conclusion that the Bowers Cave specimens are Chumash rather than Tataviam (who in 1963 were called Alliklik)[2]. "Our study ... supports a Tataviam attribution," Shanks et al. write (pg. 54), and their examination rejects a Chumash origin. They note that "Tataviam basketry is known solely from archaeological basketry"[3]; thus any attribution must be determined through a comparison to known basketry types of neighboring cultures. "Tataviam coiled basketry ... was closest technologically to that of the Gabrielino/Tongva (to the south) and inland Chumash (to the west). Yet there was a distinctive mix of features that set Tataviam coiled basketry apart from all other cultures." Tataviam twined basketry "is less known, but it does have one or more distinctive forms" (pg. 56). Shanks et al. date the Bowers Cave baskets from 1720 to 1800. Elsasser and Heizer (1963) suggest dates of 1770 (after initial European contact) to 1800. Some references place them in the cave as late as 1810. One theory is that the elders of a local village — perhaps Etseng (Piru Creek drainage) or Chaguayabit/Tsawayung (Castaic Junction) — wanted to preserve their cultural materials in the face of momentous change brought about by the arrival (1769) and establishment (1804) of Spanish missionaries and military in the Santa Clarita Valley. A major conscription of Indians into the missions occurred in 1811. Per Shanks et al.: Among the Bowers Cave specimens, five coiled baskets have long, bound-under weft fag ends[4], whereas the Chumash usually clipped their fag ends; and one basket's fag ends are tightly pinched into the foundation, which is unlike Chumash or Tongva techniques. Just one Bowers Cave basket has close-trimmed (clipped) fag ends, and this occurs in conjunction with bound-under fag ends. Five of the coiled baskets have grass bundle foundations, which is common among neighboring cultures, but two have a combination of grass bundle and juncus rod foundations, which is not. Three have a 3-rod juncus foundation. "At least one starting knot in the Bowers Cave group is unlike any known Chumash starting knots" (pg. 54). Just one Bowers Cave basket has a design; it's the mortar hopper, and while its 3-rod juncus foundation is relatively common, its pattern — three parallel bands intersected by narrow vertical lines — "is not typical of Chumash or Gabrielino/Tongva designs." Some of the basket shapes would be unusual for the Chumash or Tongva, including one with a flaring side and protruding rounded upper portion; and others with a long, inward-trending neck (pg. 54). Shanks et al. conclude (pg. 54): "Given the departure of Bowers Cave and Piru Creek baskets from typical Chumash and Gabrielino/Tongva baskets and being clearly found within Tataviam territory, they are most certainly Tataviam. This is not because we know from documented ethnographic baskets what Tataviam baskets were like. We do not. But we do know what their neighbors' baskets were like. We can rule out the likelihood of neighboring groups making these baskets. When we also see unique combinations of features and consider that these baskets are archaeologically from Tataviam territory, the case for the baskets being Tataviam is strong. 1. Bowers Cave, named for 19th-century anthropologist Stephen Bowers, is located on the current Chiquita Canyon Landfill property just outside the residential community of Val Verde in the San Martin Mountains. 2. Shanks and Shanks' Tataviam chapter was read prior to publication by Dr. John Johnson of the Santa Barbara Natural History Museum. Johnson, an expert in Tataviam archaeology and ethnology, agrees with the Tataviam attribution for the Bowers Cave specimens. 3. The authors discuss two baskets in the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County that come from the Del Valle family of Rancho Camulos. Although they are possibly Tataviam, "the cultural origin of both baskets is unknown" (pg. 53, fn.). They also discuss the two baskets in the SCV Historical Society collection that are attributed to Sinforosa Fustero, seen here and here, and note that they are likely trade items. Her coiled basket exhibits eastern characteristics, possibly Kawaiisu or Panamint Shoshone — although we don't really know what Tataviam basketry design characteristics would be, other than what's seen on the unusual mortar hopper from Bowers Cave. 4. In weaving, the fag end is the beginning of the weft, or strand, that is either coiled or twined around the warp. In basketry, a bound-under fag end is bound under some of the new weft stitches on the work surface of the basket. In Southern California, the work surface is almost always the inside, unless the basket is tiny or has a narrow neck. (The tail end of a weft is called the moving end.)

PB39243: 19200 dpi jpeg from smaller jpeg from 2.25-inch photographic negative; Peabody photo No. 2004.24.42557 (1985). |

Bowers Cave Specimens (Mult.)

Bowers on Bowers Cave 1885

Stephen Bowers Bio

Bowers Cave: Perforated Stones (Henshaw 1887)

Bowers Cave: Van Valkenburgh 1952

• Bowers Cave Inventory (Elsasser & Heizer 1963)

Tony Newhall 1984

• Chiquita Landfill Expansion DEIR 2014: Bowers Cave Discussion

Vasquez Rock Art x8

Ethnobotany of Vasquez, Placerita (Brewer 2014)

Bowl x5

Basketry Fragment

Blum Ranch (Mult.)

Little Rock Creek

Grinding Stone, Chaguayanga

Fish Canyon Bedrock Mortars & Cupules x3

2 Steatite Bowls, Hydraulic Research 1968

Steatite Cup, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x5

Ceremonial Bar, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x4

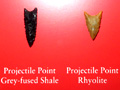

Projectile Points (4), 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig

Paradise Ranch Earth Oven

Twined Water Bottle x14

Twined Basketry Fragment

Grinding Stones, Camulos

Arrow Straightener

Pestle

Basketry x2

Coiled Basket 1875

Riverpark, aka River Village (Mult.)

Riverpark Artifact Conveyance

Tesoro (San Francisquito) Bedrock Mortar

Mojave Desert: Burham Canyon Pictographs

Leona Valley Site (Disturbed 2001)

2 Baskets

So. Cal. Basket

Biface, Haskell Canyon

2 Mortars, 2 Pestles, Bouquet Canyon

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.