|

|

Home of the Bowers Cave Artifacts

This is the entrance to the Peabody Museum as it appeared in 1968. On May 2, 1884, brothers McCoy and Everette Pyle, a pair of young ranchers, stumbled upon Bowers Cave in the Hasley hills behind Castaic. Inside they found a treasure trove of native American artifacts, believed to have been deposited there by Tataviam Indians, the dominant peoples of the Santa Clarita Valley from about A.D. 450 to the early 19th Century. Among the artifacts were nine baskets [Elsasser & Heizer 1963]; 15 complete and another 18 partial flicker (and other) feather bands [ibid.]; 45 bone whistles, various bullroarers and other items [ibid.]; and four ritual staffs or "sun sticks" — perforated stones mounted on 45cm (approx. 18-inch) wooden handles [Johnson: pers. comm. 2013] — which were likely used in the Winter Solstice ceremony [Benson 1997:32]. According to Van Valkenburgh [1952], the Bowers Cave artifacts constituted "some of the most famous Indian material ever to be discovered in the United States" inasumch as the hoard included the only perforated stones that were still attached to their original wooden handles when they were found. Nothing so important had ever been unearthed in connection with the Tataviam. Sold to Dr. Stephen Bowers, for whom the cave was named, most of the collection found its way to the Peabody Museum of American Ethnology at Harvard University. In 1952, the Peabody traded one of the ritual staffs to a museum in Australia [Blackburn & Hudson 1990:45] — traded for what, we don't know —; the bulk of the collection is still at the Peabody. Bowers Cave is located within the boundaries of the Chiquita Canyon Landfill property, near its northeastern border. An approved (2017) landfill expansion was required to avoid the cave and is unlikely to disturb it. Read Van Valkenburgh's 1952 story of his rediscovery of Bowers Cave here. Read Jerry Reynolds' 1984 story about Bowers Cave here. Photograph by Ted Lamkin in 1968.

A word about Native Californian materials in overseas museums. Blackburn and Hudson take the first comprehensive look at this topic in their 1990 work, "Time's Flotsam: Overseas Collections of California Indian Material Culture." The authors inventory tens of thousands of items — perhaps hundreds of thousands when, for instance, "misc. archaeological specimens" is listed as a single item — in 140 museums in 20 countries. To summarize: Museums trace their roots to curio cabinets kept by European royalty and aristocrats in the 16th Century. These evolved into great museums of Europe, many which were well established by the time Spain began to occupy California in 1769. Beginning in 1791 with Allesandro Malaspina (an Italian nobleman and Spanish naval officer), followed by representatives of the Russian American Co. (fur traders) along the Pacific coast, then really picking up steam under Mexican rule starting in 1822, "a respectable number of explorers, missionaries, scientists, artists and military men who visited California ... were collectors either by training or propensity" — some were better cataloguers than others — "and they returned to their homelands with a strange but often invaluable miscellany of souvenirs and specimens." The European museums filled up with booty from the land of Calafia. America was just coming into her own, and California wasn't yet part of the United States anyway. The U.S. had no major museums until the middle of the 18th Century, around the time the discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill turned American eyes westward. The Smithsonian Institution opened in 1846, Harvard's Peabody Museum in 1866, the American Museum of Natural History in 1869. They would have to play catch-up if they were to compete for prestige with their world-class European counterparts. So they sent people like Stephen Bowers to gather up as much material from California as possible — and in Bowers' case, to hurry up and do it before the French ethnographer Léon de Cessac could get it all and send it back to Paris. At one point Bowers, who did most of his collecting for the Smithsonian from 1877 to 1879 (although he generally sold to the highest bidder), decided that between Cessac and himself, they had collected so many human skulls from so many Chumash graves (they left the rest of the skeletons behind) that the museums really didn't need any more, so Bowers focused on more unique cultural items (see Benson 1997). At the time, "Chumash" was a broad identifier for peoples along the coast and for their inland neighbors including the Tataviam of the Santa Clarita Valley. Of particular interest to local readers, on a return trip Bowers purchased Tataviam cultural materials (identified as Chumash) from the discoverers of a cache cave in San Martinez Canyon near today's Val Verde community. Included were four ceremonial staffs, measuring about 18 inches, to which were attached perforated stones. Bowers had a friend at the Peabody Museum, so he sent these "Bowers Cave" items there. But that's not the end of the story. By the 1890s, the American museums were overflowing with California Indian materials — especially Chumash materials from the Channel Islands. So they began to trade them away to overseas museums for all manner of things they lacked. Among the several items the Peabody traded in 1952 to the South Australian Museum in Adelaide, Australia, was one of the four "sun staffs" found in Bowers Cave. But the Peabody was a lesser trader. By number, the biggest exporters of California's material culture were the Smithsonian; the Museum of the American Indian, founded in New York in 1916 by a wealthy collector and which by 1956 contained more than 3 million pieces; and the Denver Art Museum, whose curator from 1948-1951 was a World War II veteran who served in the South Pacific and traded many of the museum's California materials for the Oceanic objects that interested him. "As a consequence, noteworthy assemblages of California basketry that were once owned by the Denver Art Museum or formed part of (curator Eric) Douglas' own collection can now be found in museums in London, Oxford, Edinburgh, Gent, Göteborg, Stockholm and Helsinki" (Blackburn & Hudson 1990:44). "It is interesting to note that virtually all of the materials in question can be traced to only a few specific institutions: the Smithsonian Institution, the Museum of the American Indian, the Denver Art Museum, the Lowie Museum at Berkeley, the Peabody Museum at Harvard, the Field Museum (Chicago), and the Logan Museum in Beloit (Wis.)" (Blackburn & Hudson 1990:38). In sum, we see three distinct periods of removal of California Indian cultural material. First, European explorers collected ethnological materials and unearthed artifacts for several decades prior to — and several decades after — California became a part of the United States. Second, the United States, via the congressionally funded Smithsonian Institution and similar entities, exacerbated the situation in the latter half of the 19th Century and beyond by officially sanctioning "specimen"-collecting expeditions. Third, the major U.S. institutions traded away much of the collected material, scattering it to all corners of the globe.

|

Bowers Cave Specimens (Mult.)

Bowers on Bowers Cave 1885

Stephen Bowers Bio

Bowers Cave: Perforated Stones (Henshaw 1887)

Bowers Cave: Van Valkenburgh 1952

• Bowers Cave Inventory (Elsasser & Heizer 1963)

Tony Newhall 1984

• Chiquita Landfill Expansion DEIR 2014: Bowers Cave Discussion

Vasquez Rock Art x8

Ethnobotany of Vasquez, Placerita (Brewer 2014)

Bowl x5

Basketry Fragment

Blum Ranch (Mult.)

Little Rock Creek

Grinding Stone, Chaguayanga

Fish Canyon Bedrock Mortars & Cupules x3

2 Steatite Bowls, Hydraulic Research 1968

Steatite Cup, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x5

Ceremonial Bar, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x4

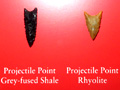

Projectile Points (4), 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig

Paradise Ranch Earth Oven

Twined Water Bottle x14

Twined Basketry Fragment

Grinding Stones, Camulos

Arrow Straightener

Pestle

Basketry x2

Coiled Basket 1875

Riverpark, aka River Village (Mult.)

Riverpark Artifact Conveyance

Tesoro (San Francisquito) Bedrock Mortar

Mojave Desert: Burham Canyon Pictographs

Leona Valley Site (Disturbed 2001)

2 Baskets

So. Cal. Basket

Biface, Haskell Canyon

2 Mortars, 2 Pestles, Bouquet Canyon

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.